Live

- Musk to invest $3 bn in India

- Sudden deluge drowns Dubai

- Grandeur marks celestial wedding in Bhadrachalam

- Revanth vs Modi: Congress braces up for Modi blitzkrieg

- Vijayawada: YSRCP accused of sheltering ‘anti-Dalit’ leaders

- Ayodhya is in incomparable bliss: Modi

- 'Surya Tilak' Illuminates Ram Lalla

- New Delhi: SC to hear plea against bail to TDP chief on May 7

- MyVoice: Views of our readers 18th April 2024

- IMD forecast bodes well for agri sector

Just In

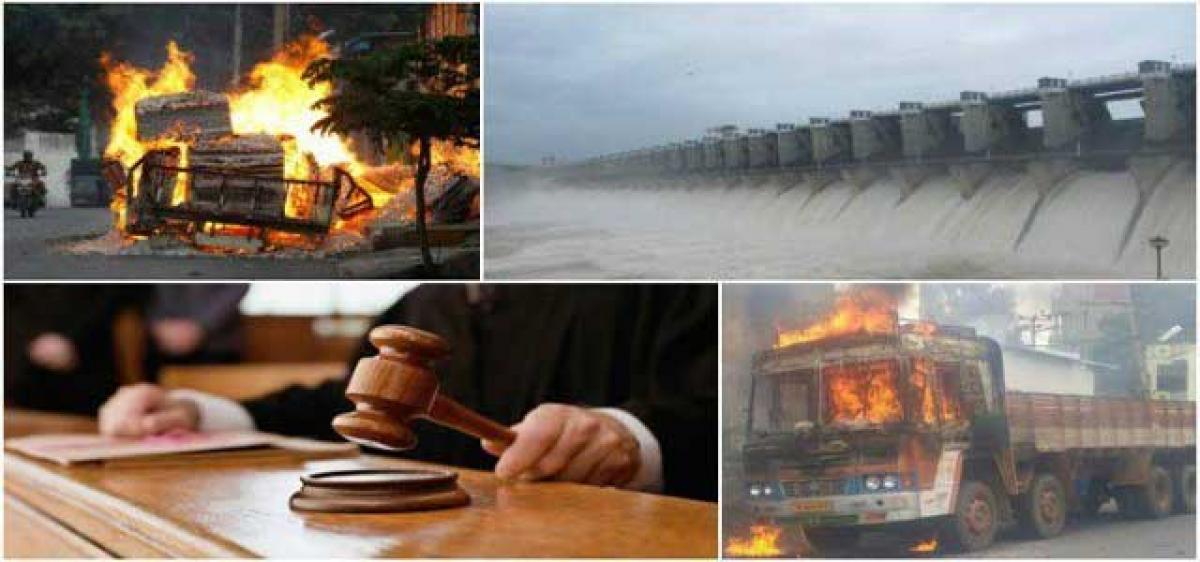

With the spur between Karnataka and Tamilnadu over the sharing of Kaveri water, the Inter State Water Dispute Tribunal has come into media attention and also has prompted the Central Government in taking a decision to set up a single, permanent tribunal to adjudicate all inter-state river disputes.

With the spur between Karnataka and Tamilnadu over the sharing of Kaveri water, the Inter State Water Dispute Tribunal has come into media attention and also has prompted the Central Government in taking a decision to set up a single, permanent tribunal to adjudicate all inter-state river disputes.

It will amend the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956 (ISWDA) to constitute the tribunal. This will help in resolving grievances of the states in a speedy manner.

Background

Although water is a state subject, as per the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956 (ISRWD Act, 1956) when any water dispute arises among two or more State Governments, the Central Government receives a request under Section 3 of the Act from any of the basis States with regard to existence of water dispute.

The Centre sets up ad hoc tribunals under ISWDA to adjudicate disputes as they arise. So far eight tribunals have been constituted.A tribunal to deal with river water disputes functions like a civil court.

According to Section 4(2) of the ISRWDA, a “Tribunal shall consist of a Chairman and two other members nominated by the Chief Justice of India from among persons who at the time of such nomination are Judges of the Supreme Court or of a High Court.

”Generally judges who are on the verge of retirement are nominated as the chairmen of the tribunals. There are no fixed hearing dates and judges can decide to hold a sitting of the tribunal at their convenience.

Some of the more prominent river water disputes tribunals include the one on Ravi-Beas among Haryana, Rajasthan and Punjab, the Krishna river dispute among Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh and the Cauvery dispute.

Article 262 provides for a specific law enacted by Parliament to adjudicate these disputes excluding the jurisdiction of all courts, including the Supreme Court.

This is due to three reasons- to disallow prolonged litigation; disputes are more political than legal; the matter is highly technical and hence must be resolved by a specialised body.

Despite this, the States have approached the Supreme Court on many occasions and it resulted in multiple jurisdictions.Concurrent adjudication complicates the matters.

The legal wrangling over river waters stretches for decades due to the current practice of having separate tribunals. It took 17 years for the Cauvery Tribunal to give its final award.

Single tribunal

- After amending the ISWDA, 1956, a permanent tribunal will be constituted.

- A retired Supreme Court Judge will be the Chair Person.

- The tribunal has to award its decision within three years.

There will be an expert agency to collect data on rainfall, irrigation and surface water flows. It is the

first step towards resolving water disputes since water data will be regularly updated and there won’t be any haste to collect data every time there is a water dispute.

This also acquires importance because party-States have a tendency to fiercely question data provided by the other side.

A Dispute Resolution Committee will be constituted to resolve the disputes before they are referred to permanent tribunal. It will comprise experts.

Challenges

- One of the reasons why inter-state river water disputes have become irresolvable is because they do not fall under the jurisdiction of any court. Courts can interpret the tribunal’s award under Article 136. The award is binding, but due to legal anomalies the decision is not enforceable. States are also non-compliant (as seen in the Cauvery dispute). Hence even if there is a permanent tribunal, this problem may persist.

- Since benches of the permanent tribunal are going to be created to look into disputes as and when they arise, it is not clear in what way these temporary benches would be different from the present tribunals.

- Given the number of ongoing inter-State disputes and those likely to arise in future, it may be difficult for a single institution with a former Supreme Court judge as its chairperson to give its ruling within three years.

Way forward

- The tribunals have failed because of competing political interests. Unless the allocation of water resources is clearly defined and there is a national consensus on it, tribunals will remain ineffective.

- The settling of river water disputes is a political issue. Unless the government deals with the political issue that most of the river disputes are made out to be, tribunal awards will continue to be bitterly contested.

- It is important to change the discourse of water management. There are limitations to litigation-centered approach.

- Water disputes have humanitarian dimensions which include agrarian problems that are worsened by drought and monsoon failures. There must be a sense of responsibility in states to consider these aspects. The disputes should be depoliticised and there must be political will to make the institutional mechanisms work.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com