Live

- Akshaya Tritiya 2024: Date and Significance

- Kamada Ekadashi 2024: Date, Auspicious Timings And Significance

- Aamir Khan’s son Junaid wraps up filming for his second movie

- Vijay Sethupathi’s heartwarming gesture wins netizens’ hearts

- Excitement builds as Nabha Natesh and Priyadarshi paired up

- Gurinder Chadha all set to make a comeback to big screen

- Palle Sindhura Reddy flays YS Jagan during election campaign in Puttaparthi

- KK Raju files nomination amid public celebrations and predicts victory with 45k vote majority

- Vijayawada Central Candidate Vellampally Srinivas Campaigns in 28th Division Railway Colony

- DCA busts three quack clinics in Hyd, Jangaon and Mahabubnagar

Just In

The trip early 2009 would be my third to Pakistan. The events of 26/11 caused me to hesitate. I chose finally to go ahead, disregarding my mother and aunt, instead heeding my daughter, who had asked me to show that not all of us hated all of them. I went partly out of a sense of professional obligation—some Pakistani colleagues had been kind enough to invite me, and I could not let them down—and

The trip early 2009 would be my third to Pakistan. The events of 26/11 caused me to hesitate. I chose finally to go ahead, disregarding my mother and aunt, instead heeding my daughter, who had asked me to show that not all of us hated all of them. I went partly out of a sense of professional obligation—some Pakistani colleagues had been kind enough to invite me, and I could not let them down—and partly out of curiosity—what would Pakistan be like at a time like this?

Leaving from Delhi, which had since my last trip to Pakistan acquired a brand—new international airport, I noticed a sign for a special ‘Haj Terminal’. When I reached my destination, I found that Lahore airport had a Haj Terminal too. There were other similarities—thus, as in Delhi, the part of Lahore closest to the airport belongs to the army.

Then again, Lahore’s main thoroughfare, the Mall Road, has large trees on its sides and elegant colonial buildings beyond. If one takes a left or right turn and drives on for a few hundred yards, one enters well-laid—out residential colonies, with spacious homes of brick and concrete guarded by private security men. However, if one chooses instead to continue down the Mall Road, one leaves the British city to enter the older, or Islamic, one.

Architecturally and aesthetically, Lahore is a sort of mini Delhi. The buildings are of three distinct types—Mughal, colonial, modern—but generally smaller and on a less expansive scale than in India’s capital. Socially of course, the city is quite different. In Lahore, as in Delhi, one sees many women in burqas and salwar kameez. But no women in saris and no men in coloured turbans, nor any in saffron robes either.

For 600 (and more) years, Lahore had been a city in which many Muslims resided and some Muslims ruled. Now, in 2009, it had for a mere sixty years and a bit been a Muslim city Even so, it remained the most broad-minded of all the towns in Pakistan. Unlike Quetta and Peshawar, Islamic fundamentalists did not dictate how people should dress or otherwise comport themselves.

Unlike Karachi, it was not crippled by sectarian violence. It retained a rich musical tradition, associated with such singers as the burly and full—throated qawwal, the late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. It was the centre of modern art and theatre in Pakistan. And the country’s best (and bravest) newspaper was published From Lahore.

One night, I was-taken to a dine at Kutu’s, a restaurant on the top floor of an ancient haveli overlooking the Badshahi Mosque. The views were nice enough, but my hosts were apologetic—apparently, on any other day in the year they would have been better still. For, it was Muharram, the Shia day of mourning, and the lights in the mosque’s courtyard were unlit. The conversation was suitably sombre, focusing on the fears of the Lahore middle class in this time of instability and transition.

On this 2009 visit to Lahore, I was mostly listening, as the people I met spoke about their hopes and fears for Pakistan. Among the latter, the threat of political Islam predominated. A town in the valley of Swat, a place once visited by many foreign tourists, had just fallen to a group of radical Islamists, whose first act was to issue an order closing down schools for women.

Meanwhile, there were reports in the newspapers of how the Taliban now owned wide swathes of property in Quetta, the capital of Balochistan. The Lahore upper class felt encircled and be1eaguered—when, they asked themselves (and me), when would their own, more tolerant and mystical form of Islam be overrun and suppressed by the fundamentalists?

A second and older threat was from the army. For much of its history, Pakistan has been run by men in uniform. This was in part a product of bad luck—the loss, so soon after Independence, of the nation's founder, M.A. Jinnah; the accident of becoming a front-line state in the Cold War, which allowed the Americans to woo Pakistan with arms and money, and hence consolidated the position of the generals.

However, it has to be said that the generals have used their good fortune to their advantage. Whereas in Delhi and other Indian towns, the army is confined to the cantonments built by the British, in Pakistan the army had captured large chunks of property inside and outside the major cities.

On the edge of the Mall Road in Lahore is a massive shopping complex owned by the army, replete with a giant wheel and bright signs for Kentucky Fried Chicken, McDonald’s and other foreign brands. The complex carries the splendidly Orwellian name of ‘Fortress Stadium’.

The generals had used their years in power to acquire the best land as well as the controlling stakes in banks and hotels. That they so dominated the economy was worrying enough. Would they, wondered my hosts, now use the pretext of bad relations with India to once more acquire control of the government?

The third fear of the middle class in Lahore in 2009 was of being abandoned by the world. The Government of the United States, once so markedly biased in favour of Pakistan, was moving closer to India. The shift was even more pronounced in the case of the American public for whom—even before the Mumbai terror attacks—Pakistan was seen as, increasingly, the most dangerous place in the world. Western states and the Western public were getting impatient with their erratic ally. By having sponsored terror while claiming to be part of the war on terror, Pakistan had wiped away, from western memory the decades of close support and solidarity in the struggle against the Soviet Union.

As an Indian, I would probably have been welcomed by my hosts in any case; but the fact that I had come when advised not to, made them even more grateful for my appearance. On my flight, there were only eighteen passengers. The stewards fell over themselves to attend on me; so did the staff in my hotel. When the time came for me to depart, I found the employees had lined up in a sort of guard of honour.

The manager invited me to come back, and to bring my friends along next time. I asked them in return to come to my homeland. One person said that he had been to India. When I asked whether it was to call on relatives or to see Mughal monuments, he answered (in Urdu) that no, he had come to see friends, and that these were a Sikh family living in Delhi whom he had befriended when they had all worked in the Gulf.

I was both moved and saddened. The young man may or may not have known that his own city Lahore, had once been a great seat of Sikh culture and Hindu learning. He certainly knew that many foreigners thought of his country as led and directed by mad mullahs. And so he wished to tell me that among his own friends was an Indian who was not a Muslim.

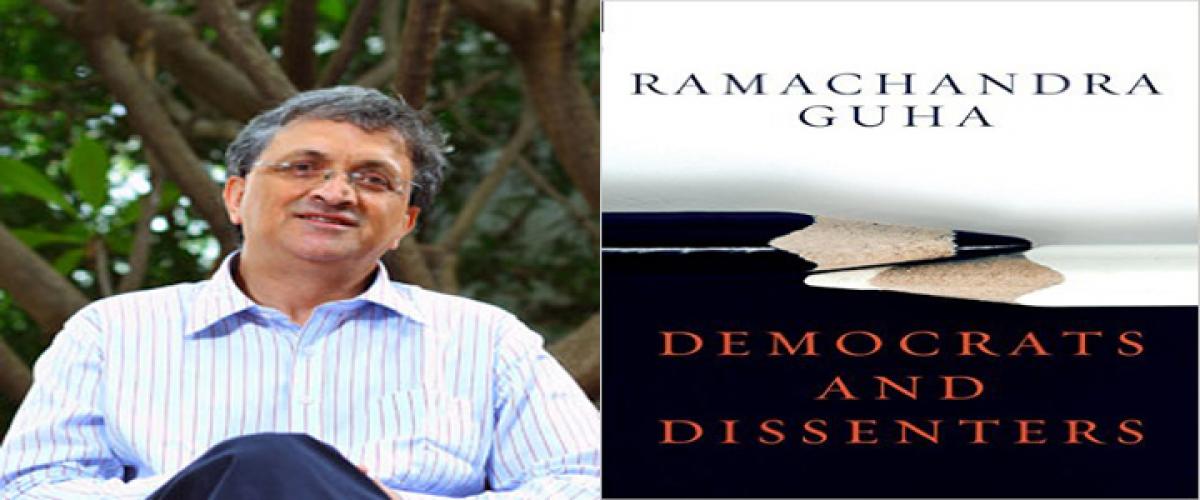

Extracted with permission from Penguin Books India, from the book Democrats and Dissenters by Ramachandra Guha

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com