Live

- World Liver Day 2024: Follow these easy lifestyle tips to cleanse and maintain a healthy liver

- Scholarships For Students

- What are the causes behind the increasing number of cancer cases

- Navigating Higher Education in US through scholarship

- Thrissur Pooram 2024: A Celebration of Tradition and Spirituality

- Akshaya Tritiya 2024: Date and Significance

- Kamada Ekadashi 2024: Date, Auspicious Timings And Significance

- Aamir Khan’s son Junaid wraps up filming for his second movie

- Vijay Sethupathi’s heartwarming gesture wins netizens’ hearts

- Excitement builds as Nabha Natesh and Priyadarshi paired up

Just In

It seems ironically heartless, but somehow the best literary creativity is inspired by tragedy, especially those in conflict situations, and can reflect its nuances and effects better.

A literary view of the Spanish Civil War

It seems ironically heartless, but somehow the best literary creativity is inspired by tragedy, especially those in conflict situations, and can reflect its nuances and effects better.

‘A Tale of Two Cities’, ‘Dr Zhivago’ and ‘Gone With the Wind’ can tell us more about the situation of the French and Russian Revolutions or the American Civil War, respectively, than any standard history, no matter how magisterial. This is also true of the Spanish Civil War.

This conflict (1936-1939), the last and bloodiest of four civil wars in Spain since Napoleonic times, was the outcome of the ideological conflict threatening to upend its social order since the dawn of the 20th century – the country had one of the strongest anarchist movements ever seen.

A precursor to the Second World War (and setting the stage for other geopolitical conflicts that have lasted well into our own times), with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy supporting the Nationalists, Stalin's Russia the Republicans, while Western democracies ineffectually tried to impose an arms embargo, it also saw a large number of foreign participants on both sides.

While the conservative and somewhat fascist strains of the Nationalist side did enjoy some support from the outside world, the preponderance was on the side of the (mostly) liberal Republicans, and it is from their supporters we have some of the most enduring memories of the conflict. Let's examine half of the dozen, ranging from the iconic to the latest.

Among them, pride of place goes to Ernest Hemingway's novel ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’ (1940), the story of an American volunteer in the International Brigades attached to a Republican guerrilla unit and assigned to blow up a bridge during an attack on an enemy-held city.

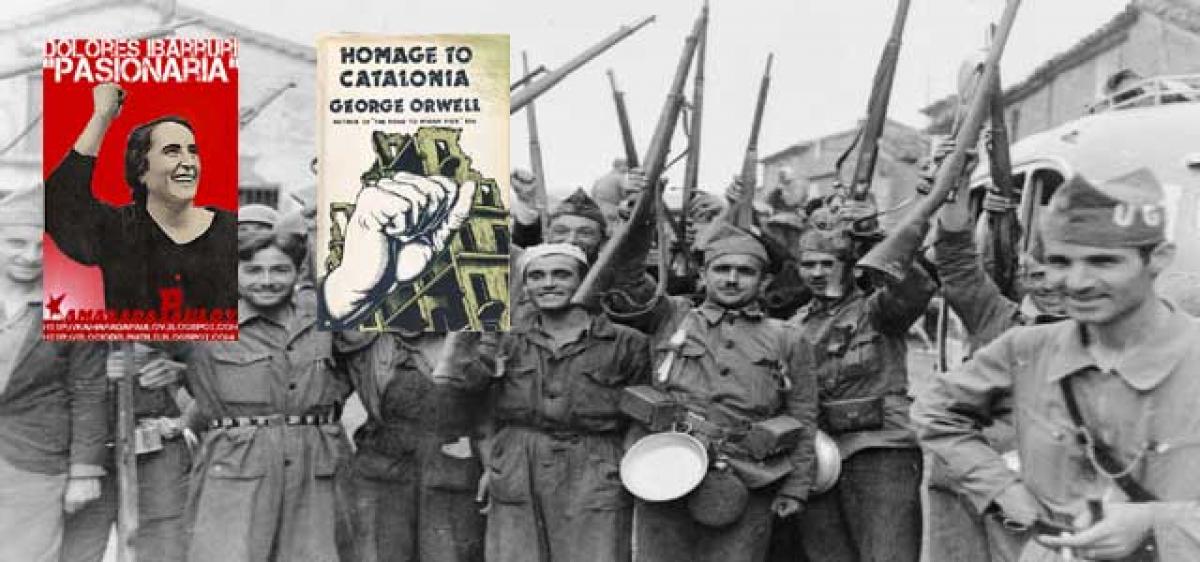

Drawing on the experiences of Hemingway, who covered the conflict for American newspapers, it has several real-life characters like Spanish Republican heroine Dolores Ibarruri ‘La Pasionaria’ (1895-1989), known for her famous slogan 'No Pasaran!

(‘They shall not pass’) during the Battle for Madrid, while some authorities believe the hero, Robert Jordan, is based on Robert Hale Merriman (1908-38), leader of the American Volunteers in the International Brigades, who was also killed in action.

The book, better known from the 1943 film adaptation starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, was nominated for the Pulitzer award in 1941 but the jury's recommendation was nixed by the then Columbia University president and no award in this category was made that year.

As searing but non-fictional is ‘Homage to Catalonia’ (1938), George Orwell's personal account of his experiences (he himself was shot by a sniper on the frontline and nearly died) and observations during his volunteer service on the Republican side.

A key motif is the lethal conflict between the anarchist militia he served in and the Stalinist Communist Party, which might have led to his negative view of the Soviet Union later expressed in his ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’.

The war forms the backdrop in one of prolific British author Dennis Wheatley's Duke de Richleau series, a modern version of Alexander Dumas's ‘Three Musketeers’ series. ‘The Golden Spaniard’ (1938), mirrors the plot of Dumas' ‘Twenty Years After’ (the second of ‘The Three Musketeers’ series), in pitting two sets of the actually four Musketeers against each other.

De Richleau is approached by Lucretia-Jose (‘The Golden Spaniard’) to save a fortune in gold in her adopted father's Madrid bank from the Republicans. Convinced to undertake the task, he finds to his surprise that among his friends, banker Simon Aron and American businessman Rex Van Ryn are unwilling to accompany him, but Richard Eaton agrees.

They find the two others are also in Spain but on the other side, and there are plenty of cat and mouse games and close shaves before all four quit the country in disgust, expressing hope that the two sides would shoot each other and leave the world in peace.

For the relation of Lucretia-Jose to the Duke, read ‘Vendetta in Spain’ (1961), which explores the Duke's first visit to Spain in the early 1900s and his fight against the Anarchists.

A recent work exploring the preliminary politics is Spanish author Eduardo Mendoza's ‘An Englishman in Madrid’ (2015, translator Nick Caistor), about an English art historian invited to Spain to value an aristocrat's collection, and falling into a collection of misadventures after meeting Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of Falange, the Spanish version of the Fascists.

A more darker work is acclaimed literary espionage novelist Alan Furst's ‘Midnight in Europe’ (2015) about the Republicans' efforts to get themselves weapons. Spanning hijacked arms in Poland, Gestapo raids in Berlin, a raid on a Soviet naval armoury in Odessa, and a tense sea battle off Italy, it shows the desperate lengths to which committed men can go for their cause.

And finally, if you prefer non-fiction, Pulitzer winner Richard Rhodes' ‘Hell and Good Company’ (2016) tells its story from the viewpoint of the reporters, writers, artists, doctors and nurses involved.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com