Live

- Scholarships For Students

- What are the causes behind the increasing number of cancer cases

- Navigating Higher Education in US through scholarship

- Thrissur Pooram 2024: A Celebration of Tradition and Spirituality

- Akshaya Tritiya 2024: Date and Significance

- Kamada Ekadashi 2024: Date, Auspicious Timings And Significance

- Aamir Khan’s son Junaid wraps up filming for his second movie

- Vijay Sethupathi’s heartwarming gesture wins netizens’ hearts

- Excitement builds as Nabha Natesh and Priyadarshi paired up

- Gurinder Chadha all set to make a comeback to big screen

Just In

One RTI applicant, Vandana, asked for information on the number of construction workers, domestic workers and women workers in the country, who have received maternity benefits in the last five years; what percentage of female workers are engaged in the unorganised sector; how are the proposed amendments of the maternity benefits act likely to cover women working in the unorganised sector; status

One RTI applicant, Vandana, asked for information on the number of construction workers, domestic workers and women workers in the country, who have received maternity benefits in the last five years; what percentage of female workers are engaged in the unorganised sector; how are the proposed amendments of the maternity benefits act likely to cover women working in the unorganised sector; status of implementation of the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act, 2008 etc. Since no information was received, the appellant approached this Commission.

Vandana, the Founding Secretary of Public Health Resource Network, is currently the National Convener. The appellant is a social activist and social worker for over two decades and has a vast experience in health and development. She has been closely associated with many national health movements like People’s Health Movement-India (Jan Swasthya Abhiyan), Mobile Crèches, Right to Food Campaign etc., to name a few. She has served as a Member (Child Health, Welfare and Development), National Commission for Protection of Child Rights from 2012 to 2013. She stated that the partial response was received after the second appeal was filed. She also submitted that 97% of the working women are in informal sector. The appellant’s second appeal gives an insight about arrangements for social welfare to women working in the unorganised sector.

Question: “How many construction workers in the country have received maternity benefits in the last five years”; Response: “Giving maternity benefits is also included in the scheme of State Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Boards but that data is not centrally maintained.”

Question: “How many domestic workers in the country have received maternity benefits in the last five years”; Response “it is stated that no data is maintained at the Central level regarding domestic workers who have received maternity benefits in the last five years.”

The other questions are: “How many women workers in the country working in any unorganised sector have received maternity benefits in the last five years”; “Of the entire female workforce, what percentage, according to the Ministry, is engaged in the unorganised sector”; “How are the proposed amendments of the maternity benefits act likely to cover women working in the unorganised sector”; “What is the status of implementation of the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act, 2008”; “What funds have been allocated for the implementation of this Act and under what heads”; “What is the status of the utilisation of these funds”; “What is the accountability of the Central Ministry of Labour towards ensuring maternity benefits for women working in the unorganised sector”; and, “What actions is the Central Labour Ministry considering in this regard.” Response: Nil.

This information should have been given under Section 4(1)(b) (xi), (xii) and 4(1)(c) of the RTI Act, which mandates disclosure of “the manner of execution of subsidy programmes, including the amounts allocated and the details of the beneficiaries of such programmes” and calls for publishing “all relevant facts while formulating important policies or announcing the decisions which affect public.”

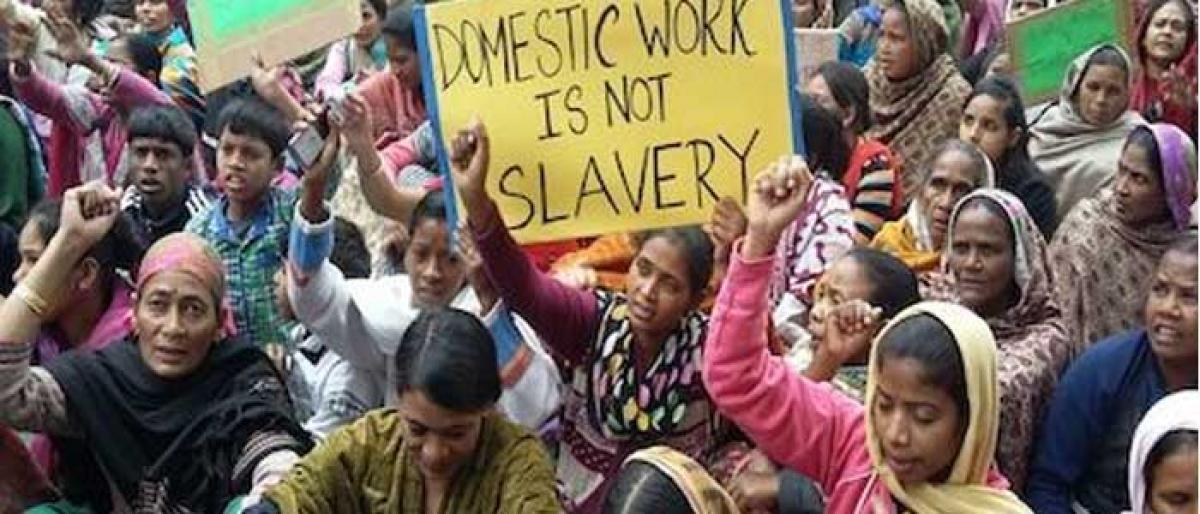

Thousands of women leave their domicile and their nearest and dearest for a better life and better career opportunities but they really get nothing. Paradoxically, they are given away to an unusual form of life which is far from reality and strained to carry on for survival with what has been offered to them. To put it in simple words, those guiltless people who have not even attained the age of majority are sold to work at factories, industries as forced/bonded labourers; women who are capable and are aspiring to become big in life are auctioned off as domestic workers.

At present, domestic workers often are given very low wages, made to work for excessively long hours, have no guaranteed weekly day off rest and at times are vulnerable to physical, mental and sexual abuse or restrictions on freedom of movement. Exploitation of domestic workers can partly be attributed to gaps in national labour and employment legislation, and often reflects discrimination along the lines of sex, race and caste.

The growing impact of domestic work in paid employment in India makes it more crucial to ensure that such work is given dignity and occurs under decent conditions with adequate pay. Appointment is done off the record and usually by word of mouth and workers rarely get benefits like insurance, paid leave, compensatory leave, gratuity, provident fund or pensions. Official figures in India suggest there are more than four million domestic workers in the country, but the real figures are almost certainly much higher. It is unfortunate to note that as long as overall productive employment generation remains slothful, the ongoing pressures will be on both male and female workers forcing to accept working conditions that are degrading.

There have been many attempts to regulate this sector since independence. Most of these have failed due to governmental resistance – active or through neglect. The Domestic Workers (Conditions of Service) Bill 1959; All India Domestic Servants Bill 1959; Domestic Workers (Conditions of Service) Bill 1972 and 1977 and The House Workers (Conditions of Service) Bill 1989 are some of the major legislations during the period. However, the government ignored the recommendations of the Committee on the Status of Women in India 1974 and the recommendation of the National Commission on Self Employed Women and Women in the informal Sector 1988.

In recent years, many NGOs and workers’ organizations have put pressure on the government to protect the rights of domestic workers. There is no national law for domestic workers and domestic workers have been excluded from various laws that provide social security benefits for workers in general. Domestic workers do not even enjoy the right to form unions. In India, domestic workers are not covered by most labour legislations because of limitation in the definition of either the ‘workman’, ‘employer’ or ‘establishment’.

The nature of their work, the specificity of employee-employer relationship, the workplace being the private household, excludes their exposure from the existing labour laws including the Minimum Wages Act 1948, Maternity Benefit Act 1961, Workmen’s Compensation Act 1926, Inter State Migrant Workers Act 1976, Payment of Wages Act 1936, Equal Remuneration Act 1976, Employee’s State Insurance Act, Employees Provident Fund Act, Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972 etc.

Fixed minimum wages, equal pay equal work, maternity leave, medical aid and other fundamental essentials provided to any employee are still an optical illusion for the domestic workers. In this background, few moves from the State governments in India should be welcomed, such as the Minimum Wage Act for Domestic Workers, which has been notified by the State governments of Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan, while a separate Act has come into force in Karnataka. Perceptibly, implementation remains a problem, but this is aided by the attempts at unionisation of such workers and related collective action, as have occurred in Kerala, Mumbai and other places in India.

The Commission found that the PIO has not forwarded the RTI application as per Section 6(3) to the authorities concerned within time. Denying or delaying in providing the information on the ground that it is not maintained will defeat the very purpose of the RTI Act. Section 8(1) which states “Provided that the information which cannot be denied to the Parliament or a State Legislature shall not be denied to any person.”

As per Section 19(5) the burden lies on public authority/CPIO to justify the denial saying they would deny the same information to Parliament also on the grounds that it is not centrally maintained. They failed to discharge this burden hence, the denial is illegal. This public authority and the Central Ministry for Labour and Employment are duty bound to take care of workers’ welfare, besides for framing appropriate policy and its implementation.

Most unfortunate that the public authority says it is not in possession of that information. The public authority has failed on two counts – one suo moto disclosure responsibility under Section 4 and discharging the burden under Section 19(5) of the RTI Act. The record shows that there was around 100 days delay in responding to the appellant. The Commission found valid reasons for admitting complaint and issued show cause notices and also notice for compensation.

(Based on the CIC decision, in Vandana Prasad v. PIO, M/o Labour & Employment, CIC/MLABE/A/2017/118245 on 11th September, 2017)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com