Live

- Applications are invited for Junior Colleges Scheme District Scheduled Castes Development Officer Ramlal

- A nomination was filed on the second day for the Nagar Kurnool parliamentary seat

- SP Gaikwad inspected the Telangana Amarnath Saleswaram Jatara yatra arrangements

- Rahul Gandhi's decision to contest from Wayanad shows 'lack of confidence': BJP President Nadda

- IPL 2024: Delhi bowlers will go after all of SRH’s top-order batters, says head coach Ricky Ponting

- At Amroha rally, PM Modi sends out ‘meaningful’ message for Muslims and Hindus

- Tripura records highest 79.83 pc voter turnout in Northeast

- The government has to clear the confusion

- UP: Police officers, govt doctors to appear virtually in courts

- White tigress Sneha dies at Nandankanan zoo

Just In

Can any educated man belittle the role of Jinnah in our freedom struggle for independence or treat him as the sole architect of Pakistan and condemn him forever? If one attempts to delve deep into the dust-laden books of pre-Independence British India, one can never ignore the supreme, significant role he played in the early struggle for freedom. Prior to his involvement in Muslim League

Can any educated man belittle the role of Jinnah in our freedom struggle for independence or treat him as the sole architect of Pakistan and condemn him forever? If one attempts to delve deep into the dust-laden books of pre-Independence British India, one can never ignore the supreme, significant role he played in the early struggle for freedom. Prior to his involvement in Muslim League for achieving a separate state, the first seed of partition was sown by Fuller, the then Governor of Bengal who was instrumental in dividing Bengal and West Bengal on Communal Lines.

Again at Simla in 1906, it was Agha Khan who went with his 35-member delegation and demanded many concessions for Muslims from Viceroy of India, Lord Minto. He received them favourably. Ramsay Macdonald admitted in his book, “The Awakening of India,”: “The authorities by showing extraordinary warmth to Muslim delegation at Simla has done great damage”

In December 1930, Md Iqbal, a noted Urdu Poet who wrote ‘Sare Jahan Se Achha Hai Hindustan Hamara”obliquely hinted at the idea of a separate North-West Muslim State, thus sowing another seed for Pakistan. The acronym “Pakistan” was coined by Chaudhry Rahmat Ali, a student of Cambridge University. He published a pamphlet in January 1933 entitled “Now or Never.” He was hailed as “Father of Psychogeography”for he came up with a series of geographical schemes for making a separate Muslim identity.

Originally, Jinnah’s grandfather was a Hindu trading in fish business. He was ostracised by his community for certain reasons and was refused to be accepted into Hindu fold. As a retaliatory measure, Jinnah’s father embraced Islam. The folly of our Hindu community led to the tragic doom of partition and its subsequent holocaust. Jinnah, from the beginning of his career always moved with top Hindu leaders and won their affection. He served Dadabhai Naoriji, the “Grand Old Man of India “as his Secretary and was associated with the moderates among Congress leaders, particularly Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and Sir Feroz Shah Mehta.

During the struggle for freedom in India, Ghokhale invited Gandhi in South Africa who earned fame for his relentless efforts in upholding the rights of Indian Immigrants. The idea was strongly supported by Jinnah who later presided over the welcome meeting arranged in honour of Gandhi in Gujar Sabha. Jinnah lauded the efforts and achievements of Gandhi in South Africa. Gandhi thanked Jinnah but added that he felt glad at a Muslim presiding over the Hindu function. This cryptic remark was ungracious, unpalatable and unwarranted for the occasion.

During the early years of his arrival from South Africa, Gandhi was little known, but Jinnah was already a prominent, acknowledged leader of the Congress. Nehru was nowhere to reckon with. In 1906 when All India Muslim League was formed to promote the interests of Muslims, he vehemently opposed its formation.

Jinnah was a liberal with a cosmopolitan outlook and assiduously strove for communal harmony.

In fact, it was he who helped reach the “Lucknow pact” which pleased both Hindus and Muslims alike. Owing to his concerted efforts in forging harmonious relations between Muslims and Hindus, he was hailed by Gokhale as “Ambassador of Hindu–Muslim unity”and later echoed by “Nightingale of India” Sarojini Naidu.

With the passing away of stalwarts like Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Naoroji and Feroz Mehta, there was a vacuum in the leadership and Jinnah felt lonely and isolated. He was very much frustrated and disillusioned. Soon Gandhi emerged as charismatic national leader and Jinnah slowly lost his centre-stage position in Congress.

From 1931-34, he was in London practising as a lawyer. An abrasive remark of Nehru that “Jinnah is finished” sent him into a fit of rage and stirred him to pack bag and baggage to India. Again, he plunged into hot politics. The return of Jinnah set the seal upon Hindu-Muslim Unity and signalled the impending tragedy of partition.

The advocacy for Pakistan by Jinnah has been strengthened and given fillip by two Indian leaders namely C Rajagopalachari and Dr B R Ambedkar. CR Suggested the formula of plebiscite and Ambedkar vigorously advocated and argued in favour of Pakistan citing numerous examples. His book “Pakistan or Partition of India“ is worth reading for justifying Jinnah’s role in creating Pakistan.

Finally, it is suggested that Jinnah did not seek a separate Pakistan but made it only a bargaining point to obtain major concessions for Muslims. In the words of Jaswanth Singh in his book captioned “Jinnah: India-Partition- Independence,” he states: “Jinnah wanted federal polity. That, even Gandhi accepted. Nehru didn’t. Consistently he stood in the way of a federal India until 1947 when it became a partitioned India.” Ayesha Jalal, a noted Pakistani historian, argued that Jinnah had no desire to split India and that partition was, in truth, a vast error. She felt that he was merely trying to strengthen his hand.

In view of the array of incidents cited, initially Jinnah was an ardent nationalist but tragically metamorphosed into a rabid communalist because of Congress leaders who despised and distanced him from their fold. Left with no alternative, he turned to Muslim League and effectively articulated their aspirations for a separate state. It must be conceded (borrowing a line from Othello) that Congress has cast away a pearl richer than their tribe by forsaking his services which turned him into an aggressive advocate of Pakistan.

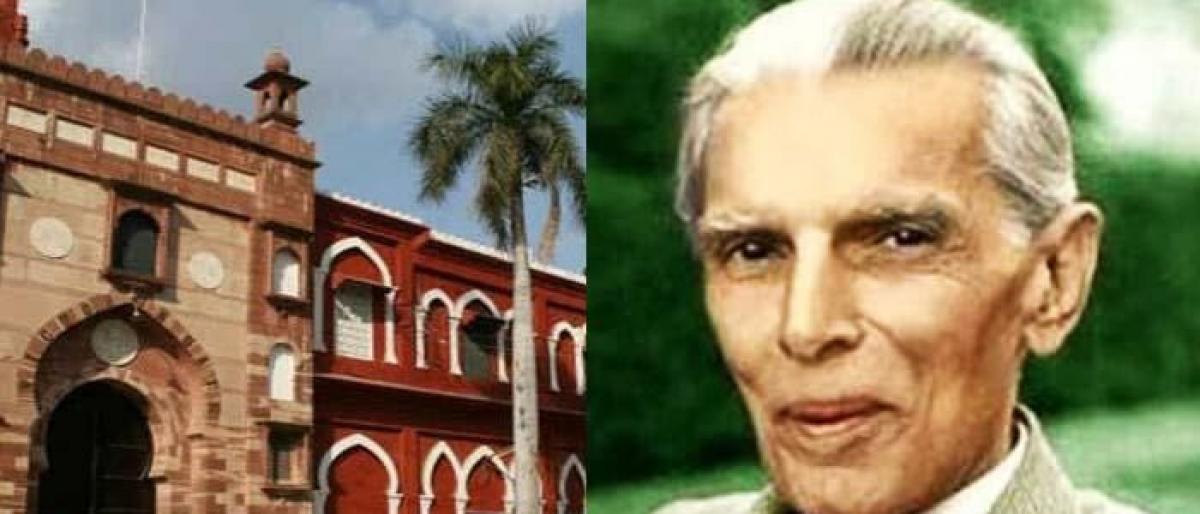

Jinnah’s role in the early stage of partition cannot be ignored and let not our young generation inherit the legacy of hatred bequeathed by our elders. Hence, the hanging of portrait of Jinnah in AMU does not imply dishonor to our nation but vindicates our veneration for the early Congress leaders of Indian Freedom Struggle.

By: Dr N K Visweswara Rao

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com