Live

- Uttam nails BRS lies on paddy auction

- Former MLA quits BJP, joins Congress

- Anil assures to complete pending projects in Palnadu

- Parchur: YSRCP govt flayed for neglecting welfare of BCs

- TSPHCL pays tributes to IPS officer Rajiv Ratan

- TSRTC to reduce bus operations between 12 pm and 4 pm

- Ram Navami 2024 Wishes & Quotes: Happy Sri Rama Navami 2024: Top 20 Wishes, Messages, and Quotes to Share with Your Family and Friends

- Jajpur: Denied ticket, BJP leader displays show of strength

- Cyberabad cops bust five online cricket betting rackets, arrest 15, seize Rs 2.41 cr

- Bhubaneswar: Temp to rise by 4 to 6 degrees C in Odisha

Just In

Brexit – the decision to exit from European Union (EU) – has badly bruised and scalded Britain. Much of the world is horrified at the collective decision the Britons arrived at, not in a jiffy, but through a referendum after weeks of campaign. It is the biggest protest against, and threat to, globalisation that has widened the rich-poor gap.

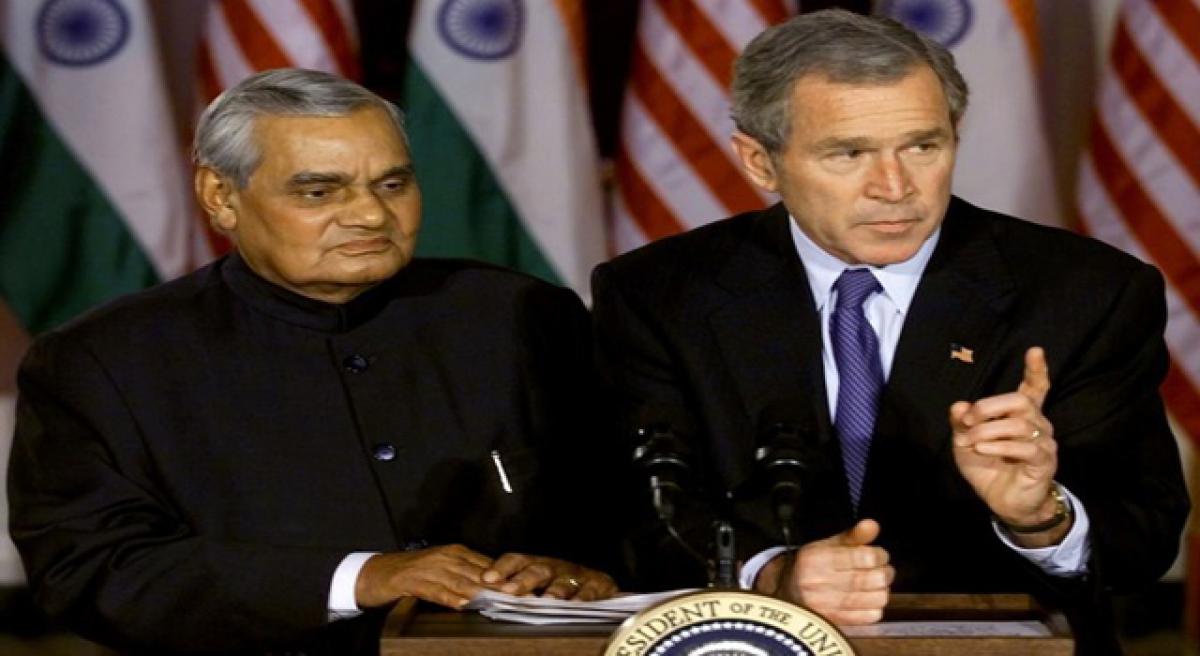

When Bush unleashed the “global war on terror” and invaded Afghanistan, India had offered all possible help, including logistics on the ground. But Vajpayee govt desisted from sending troops to Iraq. India is perceived as being very close to the US, as never before.

The moot point is: if this proximity to the US necessitates, now or in foreseeable future, sending troops abroad or making commitment of military and strategic nature to what could be America’s war, will India be able to resist it the way it did under Vajpayee?

Brexit – the decision to exit from European Union (EU) – has badly bruised and scalded Britain. Much of the world is horrified at the collective decision the Britons arrived at, not in a jiffy, but through a referendum after weeks of campaign. It is the biggest protest against, and threat to, globalisation that has widened the rich-poor gap.

Well before formally parting from EU and with little chance of a roll-back, Prime Minister David Cameroon’s government had all but politically collapsed. A Brexit opponent, he made way for someone who can guide Britain out of EU with some grace.

Strangely, major Brexit proponents like Boris Johnson who never wanted, or foresaw, a victory, with nothing by way of a contingency in case they won, fell by the way side. Theresa May is the new Prime Minister. The future is uncertain, but surely, a country like Britain is not about to wither away.

Some swear that in seeking to live in splendid isolation, Britain may benefit from Brexit in the long run. Indians hope that having resumed talks on a free trade agreement (FTA) with Britain (while disputes over a larger pact with the EU remain unresolved), India may be a net gainer. Many Indian settlers in Britain led by Priti Patel, a minister in the Cameroon team, are for Brexit.

Even before this national turmoil with international ramifications can ease, another bomb has exploded in the shape of a probe report by Sir John Chilcot on Britain’s role in the 2003 Anglo-American invasion of Iraq. Running into 2.6 million words, it roundly condemns then Prime Minister Tony Blair nd his government. Blair himself has brazened it out, justifying what he did, causing a wave of anger, and not just in Britain.

Any serious history student would see Blair’s misadventure as most calamitous British foreign policy failure since Neville Chamberlain who, on meeting German dictator Adolf Hitler, claimed that war had been averted following Germany’s invasion of Czechoslovakia.

The next was by Anthony Eden whose inept handling of the Suez Crisis in 1956 saw British troops, in collusion with the French and Israelis, seize the Suez Canal following President Nasser’s threat to nationalise the iconic waterway.

Chamberlain’s naivety was grounded in appeasement and Eden’s hubris in arrogance and chauvinism. Blair’s delusion made him invade and topple Iraqi dictator President Saddam Hussein, albeit on the coat-tails of his American political master, President George W. Bush Jr.

Incidentally, John Major, playing a similar role, followed President Bush Sr. into the 1990 Gulf war. Like the seeds of the Second World War were sown in the outcome of the First World War, Iraq’s invasion in 2003 was caused by the outcome of the Gulf war of 1990-1991.

The senior Bush arguably won the war, but Saddam survived. Its fallout was that Bush didn’t get a second term as the US President. Bush Jr. had to avenge this. The Anglo-American decision, with alibis that proved false, was taken long before.

Repercussions of that war are being felt today with great intensity. West Asia stands destabilised. The unleashing of ‘springs’ in Tunisia and Egypt, the regime change in Libya with no regime worth the name in place, sectarian violence in Iraq along with the total annihilation of one of the world’s ancient civilizations and last but certainly not the least, the rise of the Islamic State (IS) have bedeviled the region and the world. By hindsight, the 2003 war benefitted only the invaders who stole Iraq’s oil and contractors engaged in ruilding Iraq.

While the British are still debating the Chilcot report amidst Brexit’s doom and gloom, there seems to be no sign of a similar introspection in the US, the principal actor. Barack Obama hesitated to intervene in Syria, despite the grave threat the IS poses, but his people are fully engaged in trying a regime change in Syria, against Bashar al Assad.

The West in general is hunting with the hounds and running with the hares in the region. One fallout is exodus to Europe of millions of people from Syria and Iraq and northern Africa. This refugee influx is Europe’s nightmare. Whichever way one looks, Brexit is one of its consequences.

Alongside, the IS fighters are waging a war on humanity in general, but fellow-Muslims in particular, targeting the innocent in Brussels, Paris, Istanbul, Kabul and twice in Dhaka. It was easily the most violent Ramazan for the Muslims, climaxing in Dhaka on Eid-ul-Fitr.

The IS genie has arrived at India’s eastern and western gates. It is exploding inside too with cells of Islamist militants staging frequent action in various cities. But that isn’t the only reason why we are talking of the 2003 Iraq invasion. It is important for India, not only for its past, but its present and the future.

Thirteen years hence, it is necessary to recall that India got extremely close to committing troops in Iraq. Then under Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, India was on very good terms the US President Bush Jr. When 9/11 occurred, India echoed the worldwide sympathy for those dead in New York.

When Bush unleashed the “global war on terror” and invaded Afghanistan, India had offered all possible help, including logistics on the ground. There was broad consensus within the government, NDA constituents and the public.

However, Iraq was different. There were legitimate worries that this would deflect the global effort to rebuild Afghanistan. Then External Affairs Minister Yashwant Sinha had counseled at several meetings abroad against an invasion of Iraq, unless there was a United Nations mandate. Public opinion, not just in India, was against it.

But the Vajpayee government was divided. Many ministers wanted India to get pro-active and send troops. The foreign office and the military leadership were divided. Many ministers including Deputy Prime Minister Lal Krishna Advani favoured sending troops. The Army was supposed to have earmarked three Divisions to pick troops, up to 17,000 combatants, to be sent.

Many influential security experts and writers in the media felt that this was India’s chance to break out of its South Asian confines and take a pro-active role in global affairs. They argued that India would stand to gain even if it had to spend on the troops’ deployment. Given verbal commitment and a measure of assurance by top level Indians, Americans indicated that the Indian soldiers would be stationed in Iraq’s peaceful north where the Kurds are in majority.

However, Vajpayee vetoed the idea and stood his ground in the face of a large and influential opinion within his own cabinet. His feedback was that India enjoyed high goodwill among the Iraqis and should not fritter it away.

Many including Sinha and National Security Advisor Brajesh Mishra who had travelled extensively and engaged with the Americans had brought back the message that this was not a just intervention and was fraught with serious risks. The reasons given to justify the invasion, including weapons of mass destruction allegedly in Saddam’s possession were highly suspect.

Rather than confine the decision to the Cabinet Committee on Security, Vajpayee took the matter to the full Cabinet. Here, it was decided that India would not send troops to Iraq. By hindsight, it was a wise thing to do. If nothing else, India avoided bringing home body-bags of its dead soldiers from Iraq.

Today, India is politically and economically more stable than it was in 2003. Its defence forces are also larger and stronger. India is perceived as being very close to the US, as never before.

The moot point is: if this proximity to the US necessitates, now or in foreseeable future, sending troops abroad or making commitment of military and strategic nature to what could be America’s war, will India be able to resist it the way it did under Vajpayee?

By: Mahendra Ved

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com