Manu Smriti and Śūdras: Unveiling the backbone of Hindu civilisation

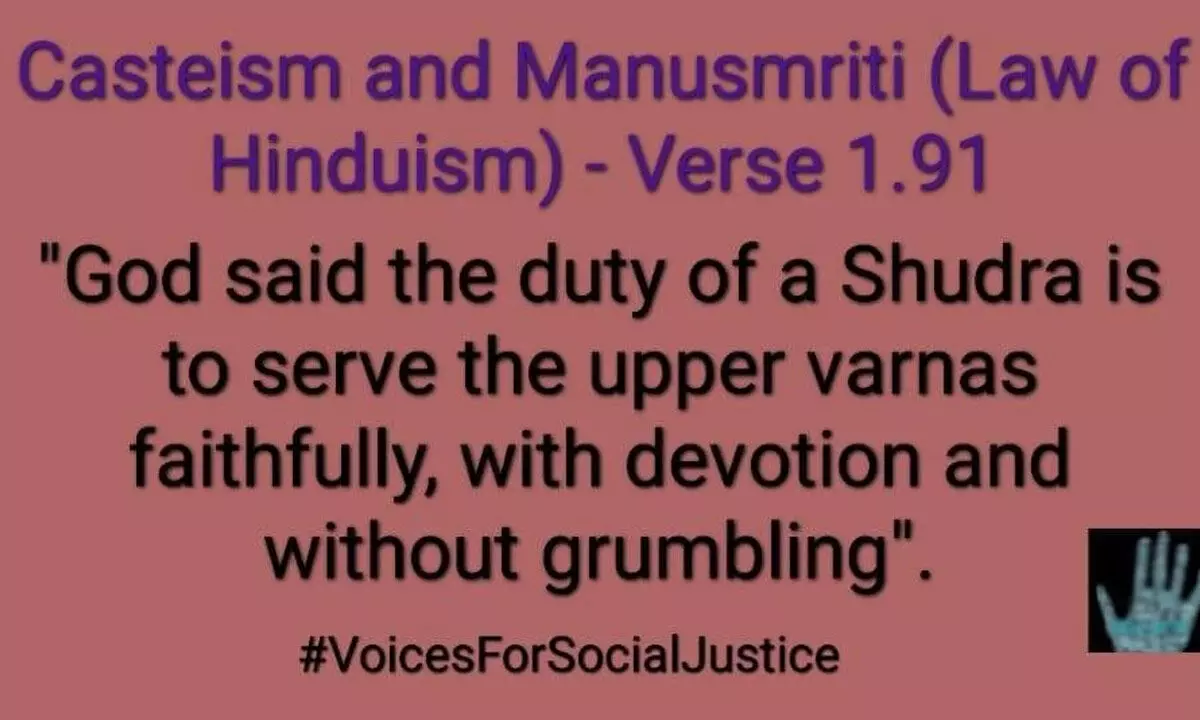

The notion that Manu Smriti verse 1.91 enforces servitude has been sustained by colonial scholars and contemporary critics alike.

Under British rule, personalities like William Jones and Max Müller viewed Manu Smriti through a Eurocentric perspective, likening the varna system to the inflexible hierarchies of European feudalism.

Misinterpretations: Alien and

modern biases

Christian missionaries amplified this distortion, depicting Hindutva as fundamentally unjust to rationalise colonial dominance.

Prophetic monotheistic faiths, such as Christianity and Islam, split humanity into believers and non-believers, embedding the latter’s subordination in their foundational texts.

For instance, Leviticus 25:44–46 in the Bible and Surah Al-Tawbah 9:5 in the Quran prescribe conversion or eradication of non-believers, labeled as heathens or kafirs, respectively. Influenced by this binary worldview, missionaries and colonial authorities approached Hindu texts with assumptions of supremacy and exclusivity, resulting in profound misrepresentations. They overlooked Hindutva’s spiritual inclusivity, grounded in shruti texts like the Vedas and Upanishads, which promote universal principles without divine commands for oppression.

Critics who assert that the Manu Smriti fosters inequality often fail to recognise its nature as a smriti—a human-crafted, adaptable law code—unlike the unchangeable doctrines of the Bible or Quran.

In post-independence India, certain scholars and activists, shaped by left-liberal perspectives, continued to portray Śūdras as oppressed labourers. The focus on servitude also ignores the breadth of Śūdra roles.

This narrative disregards the varna system’s emphasis on mutual reliance and the historical influence of Śūdra communities. Prominent dynasties, such as the Mauryas, Kakatiyas, Pallavas, Cholas, Ahoms, Chalukyas, Vijayanagara Rayas, and Marathas, were often led by Śūdras, demonstrating their capacity for significant political and military leadership, thereby challenging assertions of their marginalisation.

Varna system’s sociological brilliance:

The varna system, uniquely crafted by Hindu civilisation, was a sociological framework designed to ensure division of labour, social stability, institutionalisation of knowledge and skills, and intergenerational continuity. Unlike modern class systems, which are often based on wealth or power, the varna system was rooted in guna and karma, fostering flexibility and interdependence.

Śūdras, as producers of food and goods, formed the economic foundation, much like the grihastha in the āśrama system.

Russian intellectual Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn echoed an ancient Hindu insight, asserting that liberty and equality are fundamentally incompatible. Absolute freedom fosters inequality, while enforced equality restricts liberty; liberty disrupts social parity, and equality curbs individual freedom. By assigning complementary roles to each varna, the varna system instilled pride in one’s profession while preventing any single group from monopolising power. This ingenious framework, devised by ancient sages, created a balanced and equitable society that sustained Hindu civilisation for millennia.

Despite genocidal invasions, colonisation, and internal challenges, Hindu civilisation endured, unlike other ancient civilisations (e.g., Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Roman), which succumbed to external pressures. Its decentralised, adaptable social structure accounts for this remarkable resilience.

Śūdras as protectors and cultural stewards:

Śūdras were not only economic pillars but also protectors of Hindu geography. As the majority of the population, they formed the backbone of armies and militias, doubling as farmers in peacetime and warriors during conflicts. During the medieval period, Śūdra peasant-warriors played a crucial role in resisting Islamic invasions, preserving Hindu temples and cultural traditions. Their martial valour ensured the survival of Hindu strongholds despite immense pressure from invading forces. Similarly, Śūdra communities in the Maratha Empire under leaders like Shivaji, himself of Śūdra origin, waged guerrilla warfare against Mughal armies, safeguarding Hindu geography.

Culturally, Śūdras sustained Hindutva through oral traditions, festivals, and local practices. The Bhakti movement, led by Śūdra saints like Kabir, Ravidas, and Tukaram, re-Hinduised Hindu society, which faced extraordinary strain due to barbaric Islamic invasions and oppressive Islamic rule.

They countered the erosion of Hindu identity under foreign domination, revitalising spiritual practices and fostering unity across varnas. Their teachings enriched Hindu philosophy, reinforcing a resilient Hindu ethos that endured centuries of external threats.

Addressing modern criticisms

Critics often claim the Manu Smriti promotes caste oppression, particularly against Śūdras, but this view mistakenly equates the varna system with the later jati (sub-caste) system, which became more rigid over time. The Manu Smriti addresses varnas, not jatis, and its guidelines assign functional roles to foster societal harmony, not discrimination.

By highlighting varna interdependence—where Śūdras, as producers, enable Brahmins’ scholarship, Kshatriyas’ governance, and Vaishyas’ trade—the text builds a cooperative framework that refutes systemic oppression.

The Manu Smriti’s legal authority faded long before the modern era. By the medieval period, regional customs and local governance had largely supplanted its role, making it a philosophical and cultural touchstone rather than a binding code. Some modern activists, misunderstanding its historical context, ritually burn the Manu Smriti to protest perceived injustices. Instead of condemning the text, engaging with its original verses and historical backdrop could spark meaningful dialogue on caste and social reform, promoting understanding over division.

Many modern Hindus, estranged from their cultural heritage, revere the Indian Constitution—a rephrased version of the British-enacted Government of India Act of 1935—as if it were a sacred guide for personal and family life. They are often unaware that it is merely a manual for political governance, amended 106 times in 75 years. Arguably, many of India’s current challenges stem from this colonial Constitution. In contrast, the Manu Smriti, the world’s oldest socio-legal code, has endured for millennia, guiding Hindu civilisation to great heights and demonstrating its timeless wisdom. This underscores its enduring value, making it not only a proud heritage of Hindu civilisation but a treasure for all humanity.

Though no longer in use, the Manu Smriti still provokes unease among some Hindus estranged from their heritage and groups critical of Hindu traditions. Seeking to undermine Hindu civilisation and sow discord, they print copies of the text for symbolic destruction, often without reading it.

Such acts, rooted in ignorance and fueled by anti-Hindu sentiment, deepen animosity toward a rich cultural legacy. Society, and these individuals, would benefit greatly by redirecting their energy toward studying the Manu Smriti. Even a modest investment of time and resources in understanding its content could foster unity and appreciation of their heritage, replacing divisive actions with constructive engagement.

Though no longer in use, the Manu Smriti provokes unease among some Hindus estranged from their heritage and groups critical of Hindu traditions. Seeking to undermine Hindu civilisation and sow discord, they print copies of the text for symbolic destruction, often without reading it. Such acts, rooted in ignorance and fueled by anti-Hindu sentiment, deepen animosity toward a rich cultural legacy.

The society and these individuals would benefit greatly by redirecting their energy toward studying the Manu Smriti. Even a modest investment of time in understanding its content could foster unity and appreciation of their heritage, replacing divisive actions with constructive engagement.

Judging the past through

a balanced lens

The Manu Smriti, like any ancient text, must be understood within its historical and cultural context, not judged through the prism of modern ideologies, particularly those tinged with anti-Hindu biases. It is not my argument that the Manu Smriti should be revived as the law of contemporary India—far from it. Instead, we should refrain from evaluating the past with present-day standards, which often distort our understanding of history. Who are we to pass judgment on the complexities of ancient civilisations?

Our task is to study history, drawing inspiration from its virtues and learning lessons from its shortcomings to foster progress. By vilifying texts like the Manu Smriti without engaging with their content, we risk alienating ourselves from the rich heritage that shaped Hindu civilisation.

Embracing a balanced approach—acknowledging both the text’s contributions and its limitations—allows us to appreciate the Śūdras’ foundational role and the varna system’s ingenuity, while continuing to evolve toward a brighter future.

Conclusion

The Manu Smriti honours Śūdras as vital contributors to society, portraying them as food producers and wealth creators, not servants. In the Rig Veda’s Purusha Suktam, Śūdras are metaphorically depicted as the legs of the societal Purusha, providing mobility and stability to the social framework.

Misinterpretations of verses like MS 1.91, compounded by later interpolations and colonial distortions, have obscured this truth, fostering a skewed perception of the text’s intent.

The varna system, as outlined in the Manu Smriti, balanced liberty and equality—a tension noted by Russian philosopher Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn as inherently challenging.

By assigning complementary roles—Brahmins as scholars, Kshatriyas as protectors, Vaishyas as traders, and Śūdras as producers—the system cultivated professional pride (varna dharma) and prevented power monopolies. Rooted in guna (qualities) and karma (actions), this structure ensured Hindu civilisation’s resilience against invasions, colonisation, and internal challenges, unlike ancient Egyptian or Roman civilisations.

Approaching the Manu Smriti with an open mind, modern Hindus can dispel myths of oppression and celebrate Śūdras’ foundational contributions. The text envisions a dharmic society where every varna, including Śūdras, collaborates for collective prosperity, positioning them as essential pillars of stability and progress.

Beyond its historical legal role, the Manu Smriti offers timeless insights into a harmonious social order. By studying it, Hindus can reconnect with their cultural heritage, recognising Śūdras as indispensable stewards of a vibrant, enduring civilisation.

(The writer is a retired IPS officer, and a former Director of CBI.

Views are personal)