MERGER OF PRINCELY STATES & DECLINE OF HINDU CIVILISATION

At the time of India’s Partition and independence, there were 562 princely states as enclaves within the Dominion of India, covering 40% of its area and comprising 23% of its population.

At the time of India’s Partition and independence, there were 562 princely states as enclaves within the Dominion of India, covering 40% of its area and comprising 23% of its population. Of these, 14 were ruled by Muslim Nawabs, while the majority of their populations were Hindu. The remaining 548 states were ruled by Hindu Maharajas and Rajas and had Hindu-majority populations, with the exception of Jammu & Kashmir, which had a Muslim-majority population.

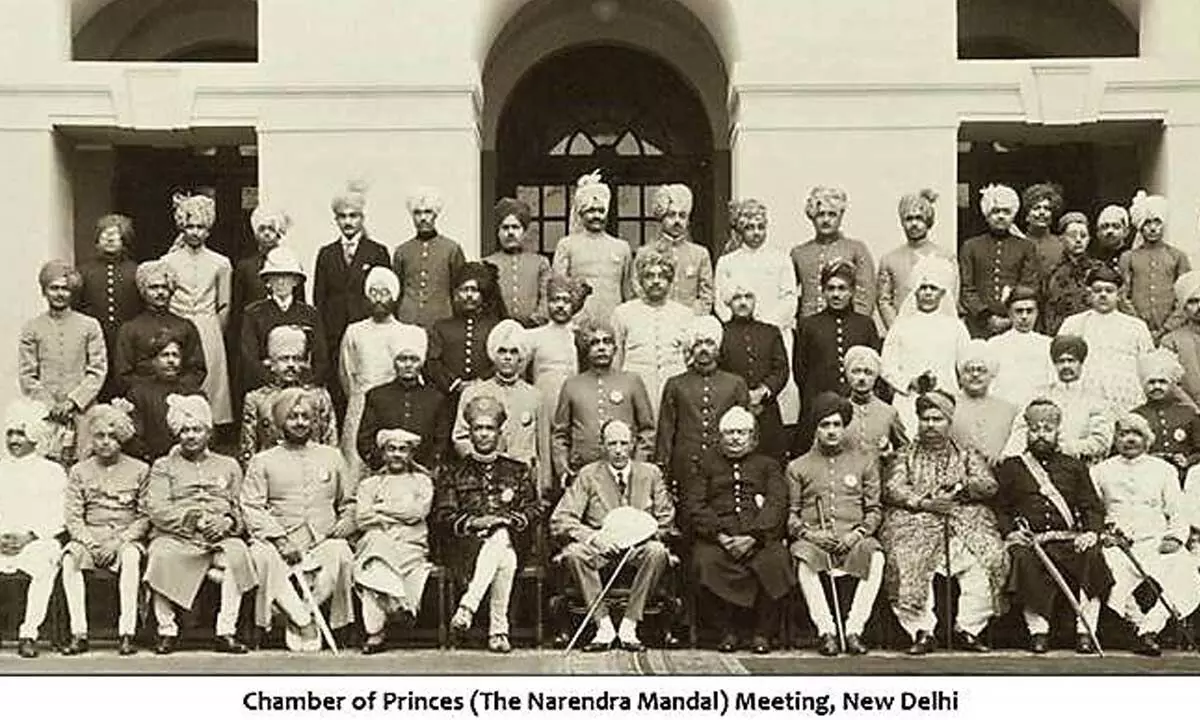

A Princely State (also called a Native State) was a nominally sovereign entity within the British Raj that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an indigenous ruler under a form of indirect rule. These states were subject to a subsidiary alliance and the suzerainty or paramountcy of the British Crown. In other words, Princely States were Protectorates of the British Crown.

The merger of all these 562 Princely States into the newly independent India in 1947-49, a project spearheaded by the Indian National Congress under leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, is often celebrated as a triumph of national unity. However, from a Hindu standpoint, this merger represents a profound civilisational loss—an event that stripped Hindu religion, culture, and demography of their traditional protectors and plunged them into an orphan-like existence within a secular, and arguably anti-Hindu, framework. This article argues that the dissolution of these 548 Hindu kingdoms, which had long served as bastions of Hindu Civilisation during centuries of colonial and pre-colonial challenges, was a shortsighted imposition of Western-style nationalism that ignored India’s unique historical and cultural reality. It further contends that alternative governance models, such as retaining the Princely States as Protectorates, could have preserved Hindu interests more effectively, and that the lack of national debate on this merger and the subsequent constitution-making process reflects a deeper failure of democratic legitimacy.

The Role of Princely States as Guardians of Hindu Civilisation

For centuries, the Princely States—most of which were Hindu kingdoms ruled by Rajas and Maharajas—served as the bedrock of Hindu religion, arts, architecture, music, literature, and temple-building. Under British colonial rule, when direct governance neglected indigenous traditions in many regions, these semi-autonomous states remained vital sanctuaries of Hindu culture. Rulers like the Maharaja of Bolangir (Patna Kingdom) in Odisha exemplified this role by actively resisting fraudulent conversions of Hindus, thereby safeguarding the demographic and spiritual integrity of their people. Temples were built and maintained, festivals were celebrated with grandeur, and Sanskrit learning was patronised, ensuring that Hindu civilization thrived despite external pressures.

This protective role was not merely cultural but existential. For over a millennium, India faced relentless invasions and assaults on its Hindu identity—first from Islamic conquests and later from British colonialism. The decentralised nature of Hindu kingdoms allowed them to adapt, resist, and preserve their traditions in ways that a centralised authority could not. Far from being relics of feudalism, as Congress and other leaders often portrayed them, these states embodied a resilient model of governance that had sustained Hindu civilisation through adversity. The Congress’s Contempt and the Imposition of Secular Nationalism

The merger of these Princely States into a secular India was driven by a Congress central leadership that displayed palpable disdain for Hindu rulers while extending leniency to Muslim Nawabs and Nizams, such as those of Hyderabad and Bhopal. Nehru and Patel, steeped in a deracinated vision of Westphalian nationalism, viewed the Rajas and Maharajas as impediments to their dream of a unified, modern nation-state. This "One Nation, One State" ideology, borrowed from Europe, ignored India’s historical reality as a single civilizational entity composed of many states—a structure that had ensured Hindu survival against "incessant deadly onslaughts" for over a thousand years. The process lacked any semblance of national consensus. There was no public debate or discussion about the future of the Princely States or the broader governance model for India. Instead, the Congress rammed through its vision, dismissing the possibility that these Hindu kingdoms could continue to play a constructive role in a post-independence framework. This top-down imposition reflected not just a rejection of Hindu rulers but a broader alienation from India’s civilisational ethos, which Congress leaders often saw as backward or divisive.

The Orphaning of Hindu Civilisation

The consequences of this merger were immediate and enduring. With the dissolution of the Princely States, Hindu religion and civilisation lost their traditional patrons—rulers who had the authority, resources, and will to protect and promote Hindu interests. In their place emerged a secular Indian state that, far from being neutral, tilted against Hindus while favouring the so called minority Muslims and Christians. The rapid decline of Hindu demography, culture, and influence since 1950 is empirical evidence of this shift. Census data reveals a steady decrease in the Hindu population percentage, while temple properties have been encroached upon, Hindu religious institutions have been undermined by state control, and Hindu customs and practices have been subjected to disproportionate scrutiny and regulation.

In contrast, the few Muslim-ruled states like Hyderabad and Bhopal were treated with kid gloves during integration, and their legacy has been preserved with greater sensitivity. This disparity underscores a troubling bias: while Hindu rulers were vilified as feudal despots, Muslim Nawabs were accommodated, revealing the Congress’s selective secularism as a thinly veiled anti-Hindu stance. The result was a nation where Hindus, despite being the numerical majority, became a civilisation without a state to call their own—a stark departure from the pre-independence era when Princely States provided localised yet robust protection.

A Missed Opportunity: Princely States as Protectorates

An alternative path was possible and, from a Hindu perspective, preferable. The Princely States could have been retained as Protectorates of India, much as they were under British paramountcy. This arrangement would have allowed them to maintain their internal autonomy while aligning with India on defence and foreign affairs. Such a federal structure would have preserved the Hindu character of these states, enabling them to continue their role as cultural and religious guardians. It would also have respected India’s historical diversity, avoiding the abrahamic homogenising impulse of Congress’s nation-building project.

This model was not without precedent. The British had successfully managed a similar relationship with the Princely States, and post-independence India could have adapted it to suit its needs. By doing so, Hindu interests—demographic stability, temple protection, and cultural patronage—might have been safeguarded in at least some regions, countering the secular state’s tendency to marginalise them. Instead, Congress opted for total absorption, erasing a system that had proven its resilience over centuries, and thereby proved to be far more anti-Hindu than the British.

The Flawed Constitution-Making Process

The merger of the Princely States was compounded by the undemocratic framing of India’s Constitution. The Constituent Assembly, constituted by the colonial British, tasked with drafting it, represented hardly 15% of Indians, heavily skewed toward Congress loyalists and deracinated elites. There was no national debate about the type of constitution India needed—whether it should reflect its civilisational heritage or mimic Western models. Instead, the Congress imposed a paraphrased version of the Government of India Act, 1935, infused with special rights and privileges for minorities that effectively weaponised it against Hindus.

This constitution entrenched the secular state’s anti-Hindu bias, from the control of Hindu temples by government bodies (while leaving minority institutions untouched) to the prioritisation of minority appeasement over majority rights. The lack of broader representation or discussion meant that the voices of the Hindu masses, and traditional leaders were sidelined, cementing a governance framework alien to India’s historical ethos.

The Need for Research and Reflection

The merger of the Princely States and its aftermath demand rigorous study. The decline of Hindu religion, civilisation, culture, languages and demography since 1950 is not a coincidence but a direct consequence of this integration into an anti-Hindu secular framework. Scholars must investigate how the loss of these Hindu kingdoms weakened the community’s ability to resist demographic shifts, cultural erosion, and state overreach. They must also explore whether alternative models, like protectorates, could have balanced national unity with civilisational preservation. From a Hindu standpoint, the Congress’s actions in 1947-49 were not a unification but a betrayal—a dismantling of the very structures that had sustained Hindu identity through history’s darkest chapters. India’s survival as a Hindu civilisational nation for millennia was not due to centralised power but to the decentralised resilience of its many states. By ignoring this truth, the Congress condemned Hindus to a future of vulnerability, a legacy that continues to haunt the nation today. Only through honest reflection and bold reimagination can this historical wrong be understood and, perhaps, redressed.

(The author is a retired IPS officer and a former Director of CBI. Views are personal.)