Live

- VIT Engineering Entrance Exam (VITEEE) from today

- BJP demands removal of ‘biased’, ‘incompetent’ officers

- Prof Vani takes charge as Dean in SPMVV

- My Dear Donga: trailer get grand launched

- Supreme Court reserves verdict

- Poll battle begins

- Phase 1 polls in 102 seats across 21 states today

- 39 candidates file papers on Day 1

- ED arrests AAP MLA Amanatullah Khan in Waqf Board appointment scam

- LS polls: Union Minister Bhagwanth Khuba, Dingaleshwara seer, Priyanka Jarkiholi file nominations in K'taka

Just In

x

Highlights

India is blessed with an extraordinary geological feature that may provide a natural solution to the problem of climate change, according to some geologists.

India is blessed with an extraordinary geological feature that may provide a natural solution to the problem of climate change, according to some geologists.

India is blessed with an extraordinary geological feature that may provide a natural solution to the problem of climate change, according to some geologists.

Scientists have known for years that carbon dioxide (CO2) from the burning of fossil fuels has been warming the planet. The just-concluded meeting in Paris urged nations to cut their CO2 emissions to ensure that the global temperature does not rise more than 2 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level, while aiming for a 1.5 degree limit.

But some experts, like law professor Dan Farber of the University of California-Berkeley, doubt whether even the 2 degree goal can be achieved purely through emission cuts, suggesting other avenues must be explored.

India has indeed an additional option, some geologists believe. This consists of capturing the CO2 coming out of coal-fired power plants and injecting it below the Deccan Traps for permanent storage.

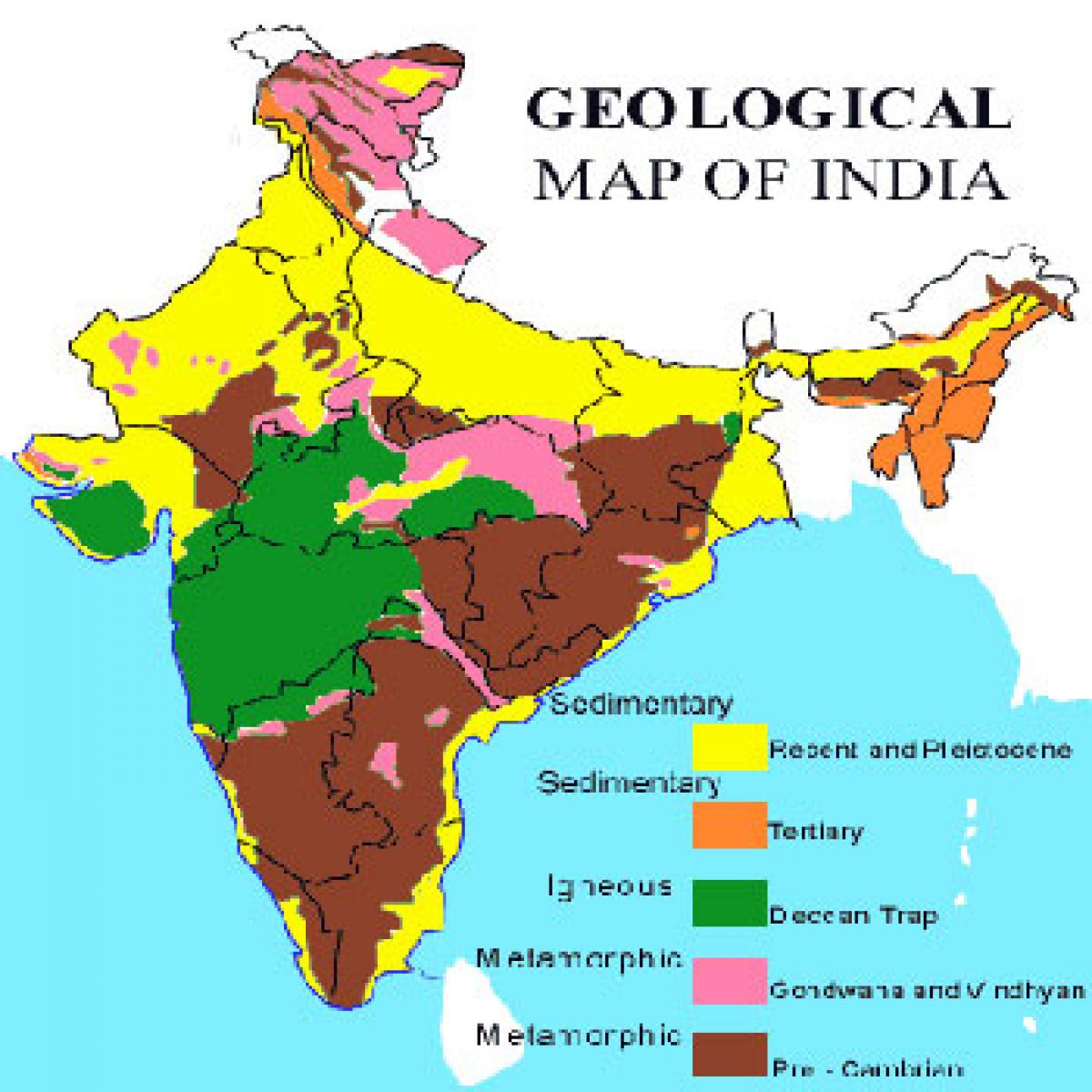

Deccan Traps - a thick pile of solidified lava from volcanic eruptions 65 million years ago - occupies about a third of peninsular India and is the world's largest continental flood-basalt province outside Siberia. The trap cover varies in thickness from a few hundred to a few thousand metres and, below this, lie thick sedimentary rocks. The idea is to pump the CO2 through the porous sedimentary rocks and use the basalt layer above as a "cap" to stop the gas escaping.

"The Deccan volcanic province in India is promising and provides enough material for CO2 sequestration," Delhi University geologist J.P. Shrivastava, told this correspondent on the phone.

He says his laboratory studies have confirmed that CO2 reacts with calcium, magnesium and iron rich silicates in the lava, turning them into stable carbonate minerals such as calcite, dolomite, magnesite and siderite. Ramakrishna Sonde, formerly executive director of the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) had estimated that Deccan Traps might be able to hold 300,000 million tonnes of CO2 - as much as humans produce in 20 years.

Realizing the potential of Deccan Traps as long-term CO2 storage option, Indian government agencies, jointly with American scientists, proposed in 2007 a field study to investigate the feasibility of this. Motivation for the project came from research at the Battelle Pacific North-West National Laboratory (PNNL) in Washington State. The US Pacific Northwest has basalt deposits similar to the Deccan Traps with an estimated holding capacity of more than 50,000 million tonnes of CO2.

The Indian study, proposed by NTPC, was to be carried out in partnership with Hyderabad's National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI) and PNNL. It was one of the 17 initiatives endorsed by the Carbon Sequestration Leadership Forum (CSLF), a 23-member voluntary climate initiative of which India was a founding member. But, according to CSLF, the Indian study has remained "inactive".

"Interest on the Indian side waned after it became clear in 2009 that no binding international emissions agreements were going to happen any time soon," Peter McGrail of PNNL told this correspondent in an e-mail. "I am not sure if the Paris agreement will change anything - too soon to tell," he added. Officials at NTPC did not reply to a query on why the study failed to take off.

While the Indian study got stuck, McGrail said "there has been some real progress" on small trials of CO2 injection into basalts in Iceland and another in Washington State. "We just finished closing our CO2 injection well here this August after 1,000 tonnes of CO2 was injected in 2013," he said.

Shrivastava is disappointed that the govenment is giving "very little attention" to the vast Deccan basalt with huge potential for CO2 storage. "Our experiments suggest Deccan Traps stands better chances (of storing CO2) compared to the Columbia river continental basalt in the US and basaltic glass of Iceland," he said.

Not only the Deccan Traps but other basaltic rocks such as Rajmahal Traps, Sylhet Traps, Panjal Traps and many more have to be examined, he said, adding that India would benefit by reviving the stalled study in Deccan Traps.

Former NGRI director V.P. Dimri agreed.

"There is enough scope for further research in this direction," Dimri told this correspondent.

"In addition to Deccan Traps basalts, the underlying sediments and older volcanics (Gujarat and western Indian offshore) can also be studied for geological sequestration of CO2," added Om Prakash Pandey, another NGRI scientist.

One possible way to revive the Deccan Traps study, said NGRI's chief scientist G. Parthasarathy, is to use the 1-km boreholes already drilled in Koyna for injecting CO2. The Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) has, however, ruled this out. "The boreholes were drilled for investigating reservoir-triggered seismicity in the region," MoES secretary M. N. Rajeevan said. "They are unsuitable for CO2 injection studies."

Next Story

More Stories

ADVERTISEMENT

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com