Live

- GMR Airports Unveils AI-Powered Digital Twin Platform to Transform Airport Operations

- India poised to become leading maritime player: PM Modi

- Top Causes of Kidney Stones and How to Recognize Silent Symptoms

- India’s renewable energy capacity logs 14.2 pc growth at 213.7 GW

- Winter Session of Odisha Assembly adjourned sine die

- Biden calls Trump's tariff approach 'major mistake'

- After Drama Over Eknath Shinde’s Chief Minister Race, Maharashtra Cabinet Formation Faces New Tensions

- Egyptian FM, Blinken discuss recent developments in Syria

- Iran's supreme leader says Syria's developments result of US-Israeli 'plot'

- Elon Musk to Purchase $100 Million Luxury Mansion Next to Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago, Report Reveals

Just In

The content of official visits abroad by the Head of State has changed in the recent years. While ceremonies remain as they should, substantive bilateral subjects and even multilateral ones figure high on the itinerary. While retaining halo around the august office, India’s President is at times a benign initiator of matters that get followed up by the Prime Minister and his government.

The content of official visits abroad by the Head of State has changed in the recent years. While ceremonies remain as they should, substantive bilateral subjects and even multilateral ones figure high on the itinerary. While retaining halo around the august office, India’s President is at times a benign initiator of matters that get followed up by the Prime Minister and his government.

President Pranab Mukherjee’s three-nation African safari last week can be best summed up as a judicious mix of sentiments of the past and commitment for the present and the future. It was designed to go well beyond ceremonies and symbolisms.

The tour of Ghana, Cote D’Ivoire and Namibia, all three on the Atlantic, somewhat bridged a gap in that traditionally, India has had more to do with Africa’s eastern side on the Indian Ocean that also has been home to its diasporas.

The visit was part of the African outreach to consolidate ties with the continent, coming months after India held a successful India-Africa Forum III in New Delhi, attended by 40 of the 54 heads of governments/states. Vice-President Hamid Ansari returned from Morocco and Tunisia, even as Prime Minister Narendra Modi plans visits to Tunisia and South Africa.

Long years of experience in the government when he headed finance, defence and external affairs ministries that brought him in contact with African leaders have helped Mukherjee push the vistas in his talks. Adding to the traditional areas like trade and cooperation in the field of science and technology, he introduced three relatively new contexts – security relationship, energy and combat against terrorism.

India is keen to tell the world why it is seeking a place for itself in a reformed United Nations Security Council and on bodies such as the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group (NSG). Mukherjee told the Africans that they were unrepresented on the UNSC, hinting that if elected as a permanent member, India would strive to fill that void.

Mukherjee has played the firefighter during his state visits. He sought to convince the Chinese leadership last month why it should support India’s NSG membership. Judging by the ongoing debate on this in many world capitals, it must have been a difficult task.

He prepared for another such round following recent incidents of violence against African nationals, especially in New Delhi. While the government has moved in to resolve the matter and assuage the concerns of African nations and their envoys, Mukherjee had also pitched in with counsel.

"We shall have to create appropriate awareness in the minds of our youngsters who may not know the history, age-old relations (between India and Africa)...India has had trading relations with African countries for centuries and everyone of the 54 countries of Africa has a thriving Indian community doing business, industry,” he told a conference of envoys.

Although the issue has reverberated in the global media, to the credit of his hosts in the three countries, none raised it. “Nobody raised the issue and I had no reason to do it,” Mukherjee said at the end of the tour.

This diplomatic silence, however, does not absolve Indian authorities and the public of responsibility to treat the Africans, mostly young students, better. The handling was bad in that one Union Minister retorted, “Africa is also unsafe” and another blamed the media for exaggerating what he called were “minor incidents.” Of what use are Mukherjee’s announcements of increased scholarships if students are either scared away or carry back bad impressions?

There was another issue awaiting his handling. He urged Namibia, having the world’s fourth-largest uranium reserves, to make good a deal signed in 2009 on its supply for India’s nuclear power reactors. His host, President Hage Geingob, assured that he would explore ways to supply the same.

A technical team from both sides would meet “at the earliest” to discuss “the way forward,” Mukherjee told the media personnel on board the special flight that brought him back home. He said it was “not true” that India had to be a member of the NSG to avail of Namibian uranium.

However, the NSG seems a more recent obstacle. Namibia and many African nations, members of the African Union, have an understanding that they would not deal with a non-signatory of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

There is confusion among the Africans for which India suspects the Chinese hand, which is where the NPT, the NSG and other issues get mixed up. No immediate solution is in sight, whatever the NSG’s decision at its Seoul meeting. Among many symbolisms, Mukherjee was at mausoleum of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first Prime Minister who collaborated with Jawaharlal Nehru in promoting the non-aligned movement (NAM).

The memorial reminds of Nehru’s Teen Murti Museum in New Delhi. Although the Nehru-Nkrumah era is a great reminder when India-Ghana relations are discussed, neither side over-emphasised the NAM in the changed global context. The new areas of focus are security, terrorism climate change, UN reforms and much else while promoting bilateral and regional ties.

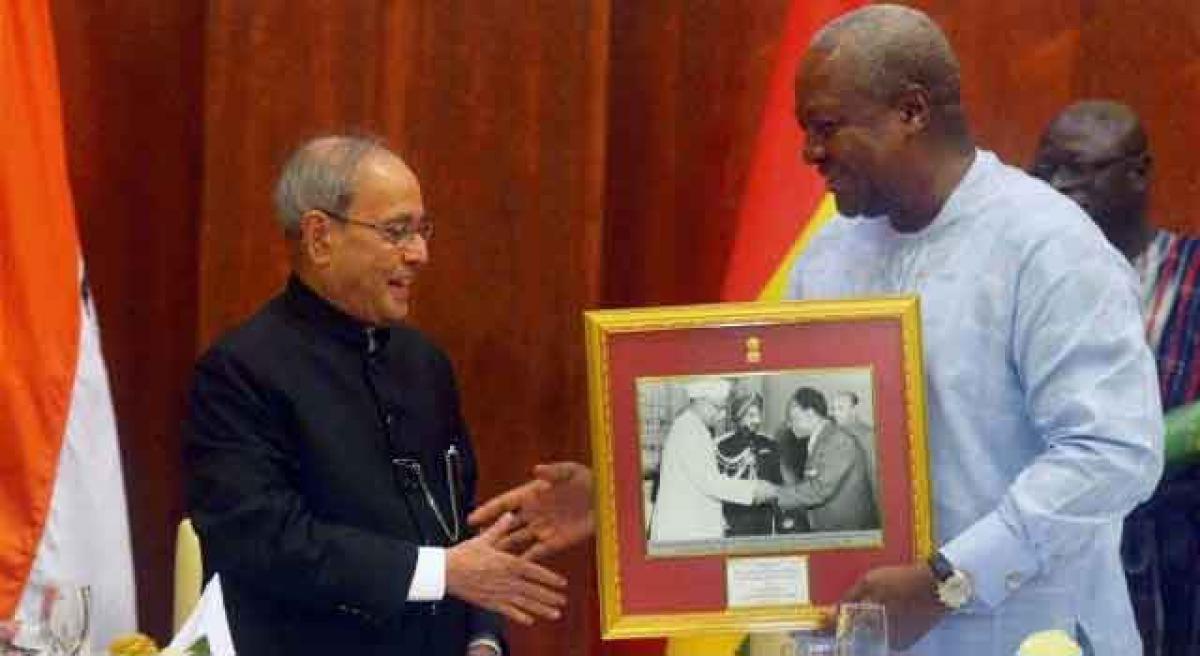

With over 10,000 of its expatriates present, India has more than indicated that Ghana is its hub for the African seaboard on the Atlantic. “India is here to help Africa,” or words to that effect marked the interactions with Ghanaian counterpart, John Dramani Mahama. “We may stumble, but together we can do a lot for our mutual progress,” he said in his address to the University of Ghana.

The principal task Mukherjee had on hand was to sell “Brand India” in the form of investment offers, small and medium industries, agro-industries, cheaper health facilities compared to the West, e-connectivity, infrastructure and much else.

Half-a-century into its technical outreach to the least developed and developing nations, India is helping create hubs of small and medium industries in some of the countries to enable job generation in those countries and add value to their exports.

The gradually emerging trend in the recent years is a win-win situation for both. It is a sign that the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) Programme, began in 1964, has come of age. What began as state-to-state drive is changing with more and more private companies setting manufacturing hubs. India is willing to put money.

While big ones have set up plants with local collaboration, the challenge still lies in getting small and medium enterprises interested in entering into such arrangements that require moving away from traditional areas, grappling with local rules and regulations and start production that takes time to start fetching profits.

Not all smaller nations are ready for hi-tech and could do with intermediary technology that India has. This requires imagination and initiative and facilitating increased participation of Indian enterprises entering uncharted or less charted territories.

At Cote d’Ivoire, setting up a plant to process cashew nuts is proposed. Coco and cashew nuts are major exports to India. Cote d’Ivoire is the second largest exporter of cashew in the world and India imports 80 percent of Ivorian exports.

With growing emphasis on information technology, several enterprises have established presence in Cote d’Ivoire making India one of the largest sources of foreign direct investment. Many Indian companies are operating in the mining and minerals sectors.

While this helps value addition for the Africans, for India, it covers the distance involved. All this has not come a day too early in that China is either already there or is coming in close with huge funds. China has stepped in with factories and funds in an area that was traditionally India’s, with its large diaspora focused on trade rather than manufacture.

All this, and more is needed to justify Mukherjee’s view that the centre of global gravity has moved to Asia and Africa.

By: Mahendra Ved

(The writer is President, Commonwealth Journalists Association. He was part of the President’s entourage during his recent three-nation tour to Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire and Namibia)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com