Live

- South Korea: Main Oppn hails Yoon's impeachment motion passage as 'victory for people, democracy'

- RG Kar issue: Tension flared over parallel protests by Congress, SUCI(C) outside CBI offices

- After furore, Central Railway revokes order to raze Lord Hanuman Temple at Dadar

- Now hoteliers' body in Bengal's Alipurduar shut doors for Bangladeshi tourists

- District Collector Encourages Students to Utilize Government Facilities for a Better Future

- Per capita availability of fruits, vegetables increases in India

- FII buying reaches Rs 22,765 crore in Dec as economic growth stays resilient

- National Energy Conservation Day 2024: Date, Importance, and Easy Ways to Save Energy

- Gastronomic trouble: After 'disappearing' samosas Himachal CM in row over red jungle fowl

- Meaningful dialogue a priceless jewel of democracy: Jagdeep Dhankhar

Just In

Let me begin this column with a hundred-year-old story of Raj Kumar Shukla, a farmer of Champaran region. He owned a few bighas of land which he used to cultivate vegetables and foodgrains, however little the quantity might have been. He was happy that he never had to borrow much from anyone to eke out his livelihood.

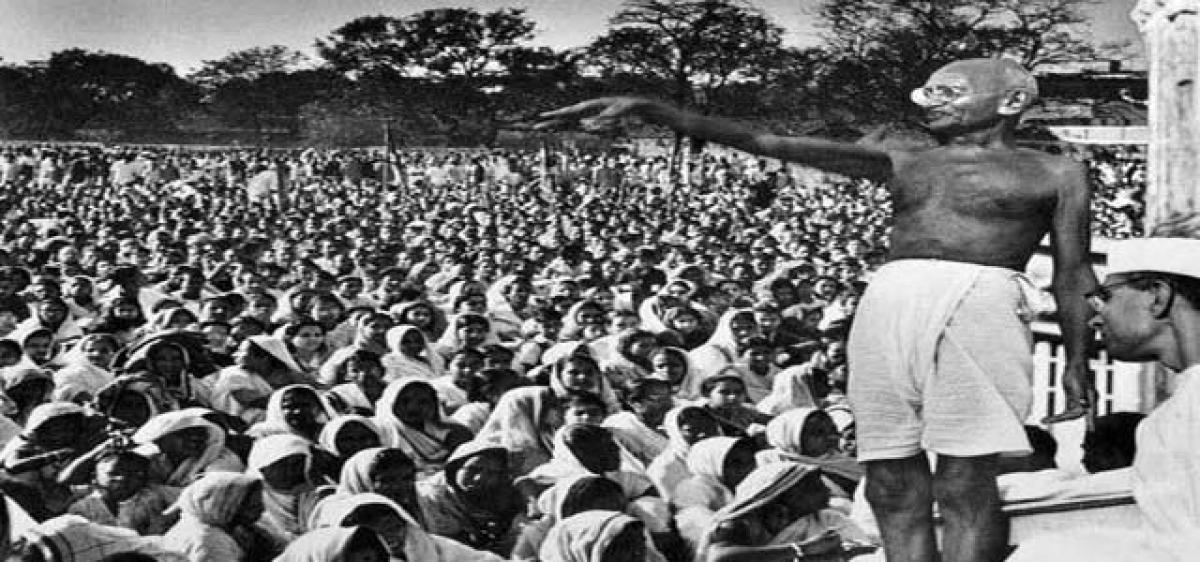

Unfortunately, unlike a century ago, we do not seem to have a visionary leader who wants to guide the masses selflessly. Those who want to lead people, plan to lead them against the governments. And that gives the ruling classes enough opportunity to blame the agitators and call them anti-social elements and anti-nationals even. We don't have to look for solutions elsewhere or borrow ideas from foreign lands. Mahatma taught the world not only how to live but also how to struggle

Let me begin this column with a hundred-year-old story of Raj Kumar Shukla, a farmer of Champaran region. He owned a few bighas of land which he used to cultivate vegetables and foodgrains, however little the quantity might have been. He was happy that he never had to borrow much from anyone to eke out his livelihood.

The good days were gone soon with the British government deciding to step in one fine day. When the then government insisted on indigo cultivation in the region, there was little choice for the farmers of the area. They were not only asked to cultivate indigo but also were forced to sell it to the government at very low price. In addition, there was heavy taxation which meant that the farmers slowly lost control over their lands and the land as well as their properties were seized by the police and the revenue authorities.

In 1914, the helpless farmers organised their first protests to no avail. They did not know how to overcome their problems. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned to India by 1915 and was settling down in Gujarat attempting to organise peasants, farmers, and urban labourers to protest against excessive land tax and discrimination.

Raj Kumar Shukla, who was an activist basically, heard of Gandhi's views and decided to approach him. He went and met Gandhi in Gujarat and sought his help in fighting the British oppression. He explained to him how the tens of thousands of landless serfs, indentured labourers and poor farmers were forced to grow indigo (poppy/opium) and similar cash crops initially by the East India Company and later by the British government. Non-permission to grow food crops had become a major disaster as their survival was being challenged by the same, he explained to Gandhi.

Suppressed by the ruthless militias of the landlords (mostly British), they were given measly compensation, leaving them in extreme poverty. While the region was facing a devastating famine too, the British levied a harsh tax and also insisted on increasing the rate. Without food and without money, the situation was growing progressively unlivable and the peasants in Champaran revolted against conditions in indigo plant cultivation in 1914 itself.

Raj Kumar Shukla could persuade Gandhi to go to Champaran. Gandhi arrived in Champaran on April 10, 1917 with a team of eminent lawyers: Brajkishore Prasad, Rajendra Prasad, Anugrah Narayan Sinha and others including Acharya Kripalani.

Gandhi's solution was simple and stunning – Satyagraha. He asked the masses to observe Satyagraha, a mass civil disobedience movement non-violently. He, however, insisted on not talking of Swaraj or independence at that juncture. He made it clear that it was not to be a political movement but a revolt against harsh conditions amidst a humanitarian disaster. He also insisted upon one more condition – that no other province revolt for Champaran. It would be a peaceful agitation of the Champaran people alone.

He also asked the Indian National Congress not to get involved apart from issuing statements of solidarity. Period. No one should politicise the movement and there should be no room for any criticism too that there were elements trying to politicise the same, he said. Gandhi had his own apprehensions that given a chance, the British would not hesitate to unleash state repression on the people and term the revolt as treason. That much care had gone into his planning.

Gandhi established an ashram in Champaran (Bihar), organising scores of his veteran supporters and fresh volunteers from the region. His handpicked team of eminent lawyers conducted a detailed study and survey of the villages, accounting the atrocities and terrible episodes of suffering, including the general state of degenerate living.

Gandhi talked to people in groups and spent a lot of time with them on all aspects of development. He made the desperate population realise that apart from freedom to grow what they wanted, they also needed education, hospitals and removal of untouchability. Purdah system should go and all women must be treated as equals, he exhorted the masses.

Not just Champaran, entire nation was watching in awe the story of Champaran struggle. It attracted several young nationalists including Jawaharlal Nehru later. Struggle led to an agreement granting more compensation and control over farming and cancellation of revenue hikes and collection of taxes until famine ended.

Sometime during this period, the masses started calling Gandhi ‘Bapu’ and ‘Mahatma,’ though a mention had already been made thus earlier by a Hindi poet. Gandhi's struggle also continued in Kheda in Gujarat where he imposed similar conditions to give the villagers not only political leadership but also a political direction.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and his colleagues organised a major tax revolt, and all the different ethnic and caste communities of Kheda rallied around it. The peasants of Kheda signed a petition calling for the tax for the year to be scrapped in the wake of famine.

The government in Bombay rejected the charter. They warned that if the peasants did not pay, the lands and the property would be confiscated and many arrested. And once confiscated, they would not be returned even if most complied. None of the villages flinched. In Gujarat, Gandhi was chiefly the spiritual head of the struggle.

Gandhi resisted the involvement of Indians from other provinces preferring to make it a Gujarati struggle. The tax withheld, the government's collectors and inspectors sent in thugs to seize property and cattle, while the police forfeited the lands and all agrarian property. The farmers did not resist arrest, nor retaliate to the force. Instead, they used their cash and valuables to donate to the Gujarat Sabha which was the organiser of the protests.

The revolt was astounding in terms of discipline and unity. Even when all their personal property, land and livelihood were seized, a vast majority of Kheda's farmers remained firmly united. Gujaratis sympathetic to the revolt in other parts resisted the government machinery, and helped to shelter the relatives and protect the property of the protesters. Those Indians who sought to buy the confiscated lands were ostracised from society.

The government finally sought to foster an honourable agreement for both parties. The tax for the year in question, and the next would be suspended, and the increase in rate reduced, while all confiscated property would be returned.

People also worked in cohesion to return the confiscated lands to their rightful owners. The ones who had bought the lands seized were influenced to return them, even though the British had officially said it would stand by the buyer.

That was 100 years ago.

Any lessons there for those planning to lead the people's struggles in AP and Telangana? Farmers losing lands to the new capital or SEZs or industries and projects, or workers and employees seeking better deal or the youth seeking employment, they are not looking to install new governments. They agitate against the injustice and oppression.

Unfortunately, unlike a century ago, we do not seem to have a visionary leader who wants to guide the masses selflessly. Those who want to lead people, plan to lead them against the governments. And that gives the ruling classes enough opportunity to blame the agitators and call them anti-social elements and anti-nationals even.

We don't have to look for solutions elsewhere or borrow ideas from foreign lands. Mahatma taught the world not only how to live but also how to struggle. He also knew where to draw the line. Today, we see only Agraha without Satya. Pity no one reads Gandhi at all!

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com