Live

- A Guide to Temperature and Humidity Standards in Data Center Server Rooms

- Gadwal collector briefs on details of voters

- Jupally Krishna Rao takes part in Alampur rallu

- Bharath Prasad files 3rd Nomination

- Baisakh Month: A Time of Auspicious Beginnings and Sacred Festivals

- Oust BJD govt for overall development, says Shah

- Unveiling the Hidden Gems: Surprising Health Benefits of Garlic Peels

- Overcoming Sleep Struggles: A Comprehensive Guide to a Restful Night

- RTC bus hit the auto

- MLA Kuchukula Rajesh Reddy participated in the Birappa festival

Just In

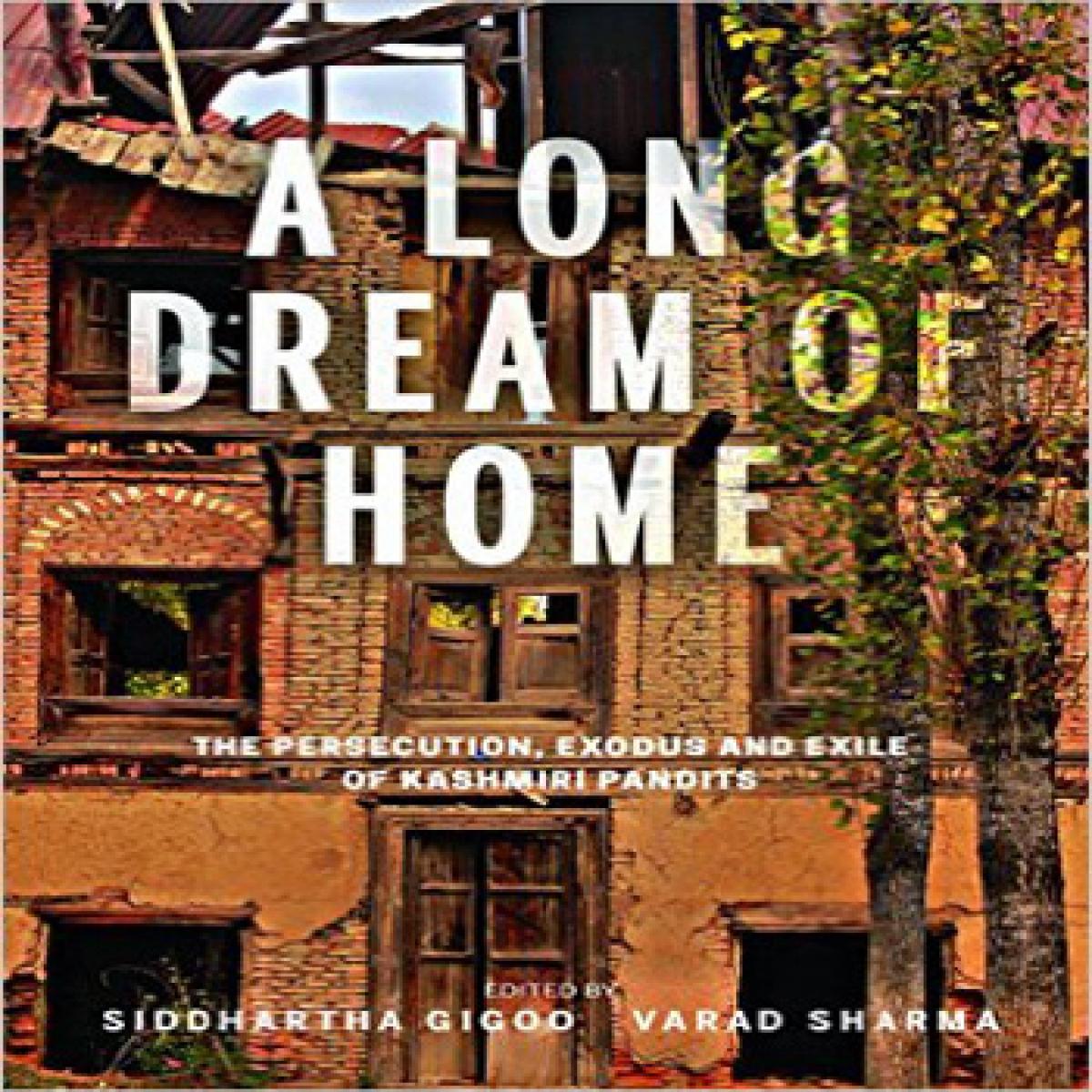

The photographs say it all – a Kashmiri Pandit girl storing water outside a canvas tent in the migrant camp in Jammu Province where the Pandits stayed from 1990 to 1993 before they were replaced by one-room tenements until 2011; rows of apartments in the temporary settlement where 4000 Kashmiri Pandit families from various locations were re-settled in 2011, the dilapidated houses, temples, abandon

Kashmiri Pandits in exile since 29 years relate the untold stories of their persecution, struggle and plight. They finally break the silence, says Siddhartha Gigoo, one of the editors of the compilation

The photographs say it all – a Kashmiri Pandit girl storing water outside a canvas tent in the migrant camp in Jammu Province where the Pandits stayed from 1990 to 1993 before they were replaced by one-room tenements until 2011; rows of apartments in the temporary settlement where 4000 Kashmiri Pandit families from various locations were re-settled in 2011, the dilapidated houses, temples, abandoned family homes, and then there are stories.

Around 29 Kashmiri Pandits of three generations with shared memories of exile from their home land, a few famous and several not so famous ones relate their experiences quarter of a century later in a compilation, collected and edited by Siddhartha Gigoo and Varad Sharma.

In her story, ‘Nights of Terror’, Meenakshi Raina says – Kashmiri Pandits have paid an enormous price for their patriotism and the nation still doesn’t recognise their pain and suffering; their voices have remained unheard over the past two and a half decades, and they continue to be called ‘migrants’, a label that was given to them in 1990 when they were forced out of Kashmir – which is the sentiment shared by all the authors of the stories.

These are the tales of struggles and plights of Kashmiri Pandit exiles that have remained untold and forgotten – shares Siddhartha. He calls the book as the end of 25 years of silence of a community with untold memoirs of the displaced from remotest of villages and towns of Kashmir who for the first time narrated the circumstances in which they had to leave their home in 1990 and go to Jammu. “The book is about what happened to them.”

He says compiling the stories was a revealing experience for him. “It was an education to me as I learnt what happened with others. At the heart of each story was a sense of persecution, everyone was asked to leave or face dire consequences. We were peaceful and identified as India.

Many of us worked for government of India, but were asked to leave because 1989 was not a call for Azadi, but a call to make Kashmir a part of Pakistan; it was a call for Islamisation of Kashmir. Those who did not leave were targeted. Handful of people stayed back but migrated from downtown to places in Srinagar that were safer.”

Siddhartha, who is himself from a family that was exiled, sounds as irate as several others and calls the anger justified. “Resentment and anger will continue to be there. We have a whole new generation that was born and brought up in the camps that feels nothing is being done. There is a desire for truth and reconciliation, There should not be politics.

We have lost entire old generations that have died and are not remembered anymore. This resentment will only intensify and manifest in the form of writings, lectures talks, updates on social media.” Even though BJP had put the issue in their manifesto, which had infact given rise to hope within the community, the attitude of Prime Minister and his colleagues baffles him.

“It’s been a year, but nothing has been done yet. Recently, PM delivered a speech in Kashmir, but he neither went to Jammu to meet the Pandit families nor did he even mention Kashmiri Pandits in his hour-long speech, which is strange and disappointing. None of his senior cabinet colleagues started a concerted dialogue towards the issue. It may not be on their priority list. However, if something can be done – now is the time.”

He says that Kashmiri Pandits and Muslims are two different issues and never spoken in the same breath, “Kashmiri pandits feel and know that ouster happened because of Kashmiri Muslims, who in turn feel that they went on their own accord. They had points of convergence and divergence. If we could return to homeland we want to go back and live how we lived…but is that possible? My writing talks about this and also about segregation and integration.”

He adds, “The good thing is that there is a vast section of Muslims who say that their life in the valley is incomplete without Kashmiri Pandits.” The book also has a story recounted by Siddhartha. Stating the purpose of compiling the book as to recount the tales and not to spread hatred, he opines, “We need to keep the memory alive and the question alive in the hearts and minds of not just politicians but also India.

We Indians, expressed our rage for Syrian refugees, but we do not talk about the Kashmiri Pandits.” On a final note he relates the collective wish of all the exiled Kashmiri Pandits - Take Kashmiris back to the valley, create sense of security, create jobs, and solve the militancy problem (which is a larger political problem and can take back Kashmir to dark era.)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com