Live

- NRIs deny they held secret meeting

- Changed political equations favour TDP in Nellore City

- Modi errs, jittery EC sends notice to Nadda

- New Delhi: LG postpones MCD mayoral polls

- MyVoice: Views of our readers 26th April 2024

- Measuring scavenging value of vultures

- Celebrating 107 Years of Osmania University: A Legacy of Academic Excellence

- Hate-hate relationship new trend in Indian politics

- Gadwal collector briefs on details of voters

- Jupally Krishna Rao takes part in Alampur rallu

Just In

Confined to his Beijing house basement for over two years during the Cultural Revolution, Reuters correspondent Anthony Grey was only allowed sporadic visits upstairs under close supervision to collect approved necessities. His reading matter was restricted but he still contrived somehow to elude his guards for the few seconds he needed to deftly snatch up and conceal his copy of ‘Doctor Zhivago’, which they had rejected earlier.

.jpg) Confined to his Beijing house basement for over two years during the Cultural Revolution, Reuters correspondent Anthony Grey was only allowed sporadic visits upstairs under close supervision to collect approved necessities. His reading matter was restricted but he still contrived somehow to elude his guards for the few seconds he needed to deftly snatch up and conceal his copy of ‘Doctor Zhivago’, which they had rejected earlier.

Confined to his Beijing house basement for over two years during the Cultural Revolution, Reuters correspondent Anthony Grey was only allowed sporadic visits upstairs under close supervision to collect approved necessities. His reading matter was restricted but he still contrived somehow to elude his guards for the few seconds he needed to deftly snatch up and conceal his copy of ‘Doctor Zhivago’, which they had rejected earlier.

The incident seems apt for a book born in strange circumstances, and going on to have its own chapter in Cold War history.The sole (and faintly autobiographical) novel by the Russian poet Boris Pasternak (1890-1960), about an idealistic physician-poet during the Russian Revolution, fell afoul of the Soviet establishment due to its apparent seditious stance and contrarian view of seminal episodes of Soviet history. It seemed fated to go unpublished – had it not been for a unique international collaboration.

Pasternak handed over the manuscript to an Italian journalist with the words, “This is ‘Dr Zhivago’. May it make its way around the world.” In May 1956, an Italian aristocrat-turned-communist publisher; Russian émigrés; American publishers and CIA operatives; Dutch intelligence officials; and Vatican priests got together to get it published and into the hands of its readers – especially in the author's country as well as other communist countries.

Meanwhile, the Swedish Academy's selection of Pasternak for the Nobel Prize in Literature (and his subsequent repudiation of the award under government pressure) brought the book to world attention – and meant further trouble for Pasternak and his family until then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru publicly weighed in.

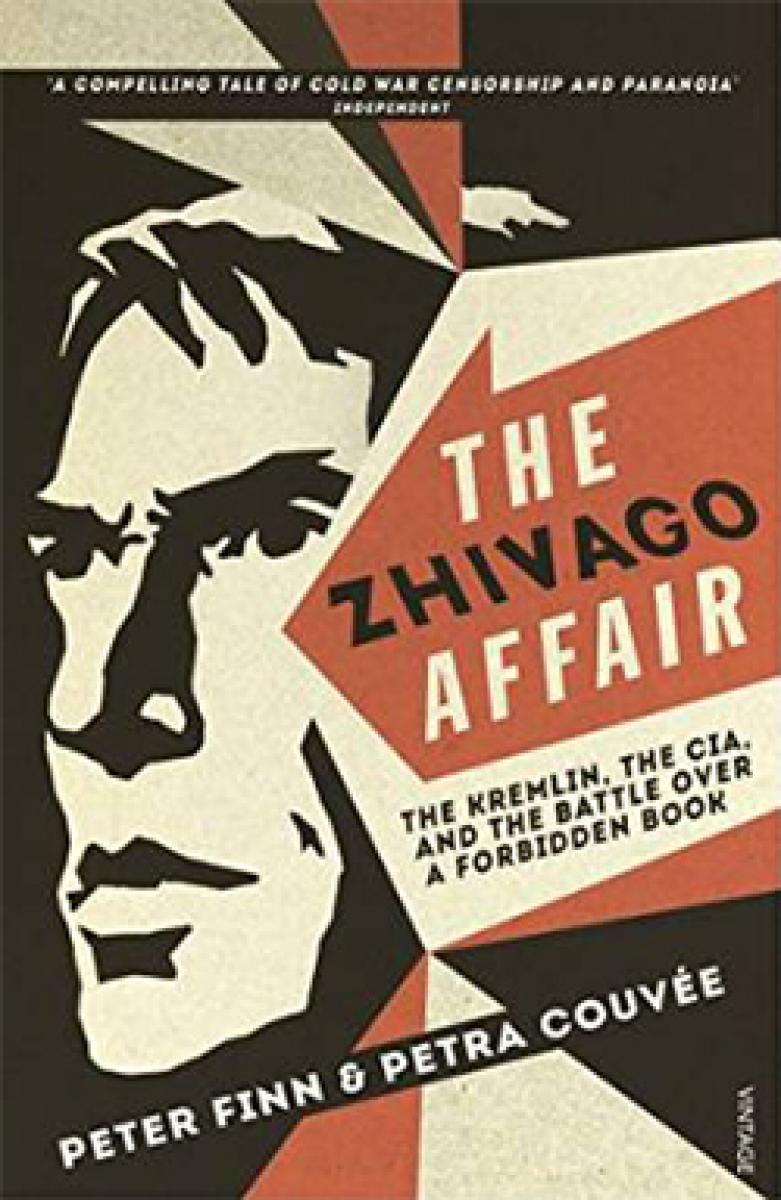

This is the engrossing story that Peter Finn, the national security editor of The Washington Post who was previously its bureau chief in Moscow; Petra Couvee, a teacher at Saint Petersburg State University; and Pasternak’s family members bring out in their first book based on information from declassified CIA files and interviews of various Europeans officials and activists involved in the events.

But their account does not only deal with the Cold War intrigues and the CIA-KGB conflict over Pasternak's novel. It is also deals with Pasternak, his interestingly complicated love life (he virtually abandoned his first wife to marry a friend's wife, who slowly grew cantankerous, while he embarked in a long relationship with another much younger woman who would suffer much for his and the book's sake).

The Soviet Union's literary climate, especially the uncertain, lethal time during the Stalinist purges when several writers perished. The short-lived Khrushchev thaw and the eventual return of political oversight and the role of culture and ideology in both democracies and autocratic polities.

There is a varied supporting cast – Pasternak's literary colleagues who were supportive, indifferent or virulently opposed leading authors and other intellectuals, maverick publishers, sinister, devious government functionaries and literary bureaucrats, family members, clandestine operatives, and more.

Also figuring is the eventually tragic story of Giagiacomo Feltrinelli, the Milan-based publisher (whose first publication was Nehru’s autobiography) with an eye for commercial opportunity, who resisted all pressure to suppress it (he himself later became a violent ultra-left militant before being found dead in mysterious circumstances).

What is missing is the literary significance of ‘Dr Zhivago’ with its skeptical and individualistic approach to the revolution and heretical (for communist ideology) stress on personal freedom above loyalty to the proletariat and Marxist-Leninist tenets.

But the true value of this book reminds us - in today’s networked world where information can be disseminated without constraint of time, space and challenges to a nation’s security are technological and financial - of an era where ideology was just as important, and literature could be a weapon of de-stabilisation. Will anyone care as much for a book today?

By:Vikas Datta

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com