ASEAN must stand up to China

ASEAN must stand up to China. The Association of Southeast Asia Nations has prided itself on its “ASEAN Way” – an informal and non-legalistic way of doing business, especially its culture of consultations and consensus that have resolved disputes peacefully.

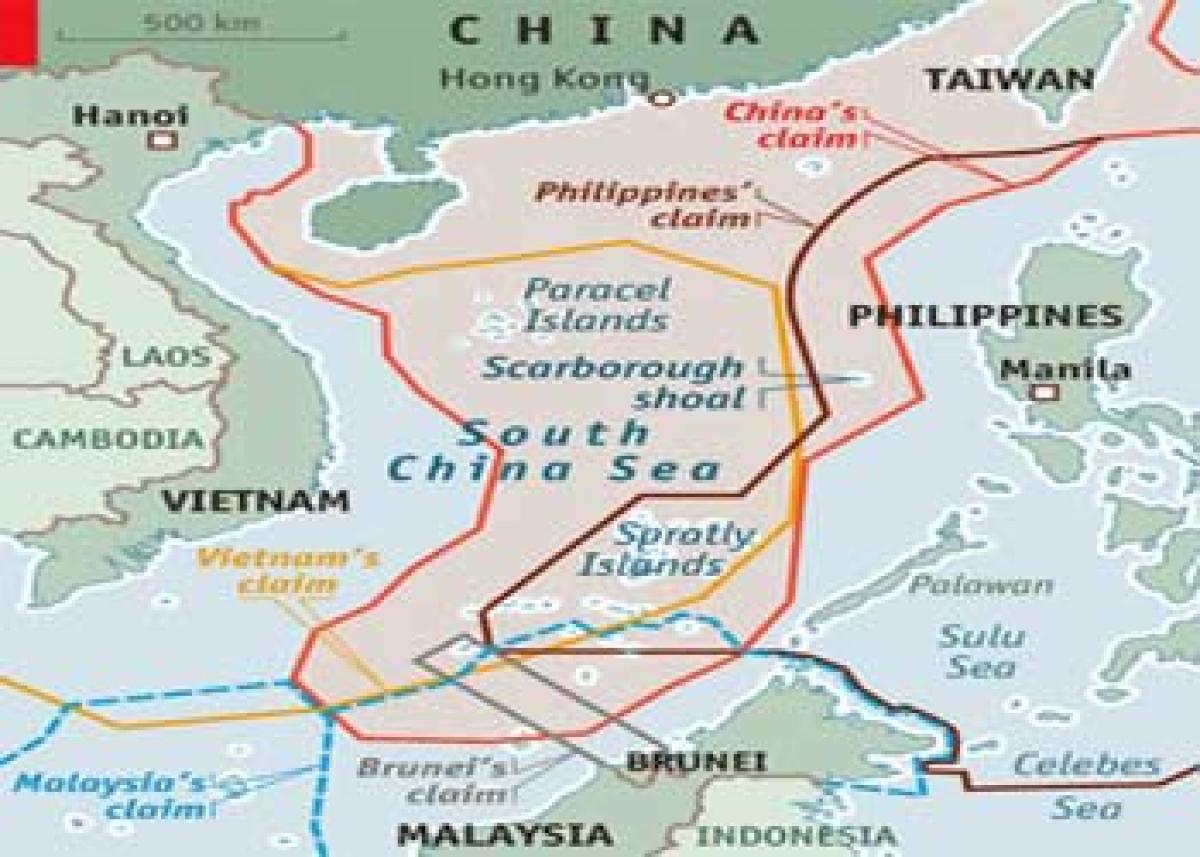

.jpg) China’s creeping expansionism in South China Sea

China’s creeping expansionism in South China Sea

The Association of Southeast Asia Nations has prided itself on its “ASEAN Way” – an informal and non-legalistic way of doing business, especially its culture of consultations and consensus that have resolved disputes peacefully. That way of doing business may be fading among signs the group’s unity is seriously eroding. Against the backdrop of the rise of an assertive China, signs of disunity spell trouble for the region. There are several reasons for this disunity.

First, ASEAN today is a much bigger entity. Membership expanded in the 1990s to include Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia, with East Timor likely to be the 11th member. With an expanded membership, agenda and area of concern, it’s only natural that ASEAN will face more internal disagreements. Without doubt, ASEAN’s main security challenge is the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. While not a new problem, the disagreement has telescoped due to recent Chinese activities.

The most recent example: China’s reclamation activities in the Fiery Reef claimed by Vietnam and Mischief Reef and surrounding areas also claimed by the Philippines. This reflects a shift in China’s approach. While the Chinese military has pressed for land reclamation for some time, the leadership of Hu Jintao had resisted such moves. That restraint ended under the leadership of Xi Jinping, who is more prone to seek the PLA’s counsel in foreign policy issues related to national security and who has advanced China’s assertiveness on economic, diplomatic and military fronts.

China is developing the islands further for both area denial and sea-control purposes and as a staging post for blue-water deployments into the Indian Ocean. These developments challenge ASEAN’s role and “centrality” in the Asian security architecture. The economic ties of individual ASEAN members lead them to adopt varying positions. Until now, ASEAN’s advantage was that there was no alternative convening power in the region. But mere positional “centrality” is meaningless without an active and concerted ASEAN leadership to tackle problems, especially the South China Sea dispute.

Episodes such as the failure to issue a joint ASEAN communique in 2012 have led to the perception that ASEAN unity is fraying and China is a major factor. As for ASEAN, it must not remove itself from South China Sea issue. If anything, it should give even more focused attention to the disputes. A decision by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, which is considering a motion filed by the Philippines challenging the legality of China’s nine-dash line, may end up in Manila’s favour. This would help ASEAN, even if China rejects that verdict.

But to make the most of such an opportunity, ASEAN would need to show collective support for such a verdict, and it might help if other claimants, such as Vietnam, also initiate similar legal action. China rejects a more direct role by the East Asia Summit, led by ASEAN anyway, because of US membership. The international community should render more support and encouragement to ASEAN to persist with its diplomacy in the conflict. And Indonesia needs to get back in this game. (Excerpts from the article originally published on YaleGlobal Online)

By Amitav Acharya