Fighting poverty: Why we always fail

The Central government plans to bring one crore households out of poverty by 2019. Such targets are announced each year, but why don’t they work?

The Central government plans to bring one crore households out of poverty by 2019. Such targets are announced each year, but why don’t they work?

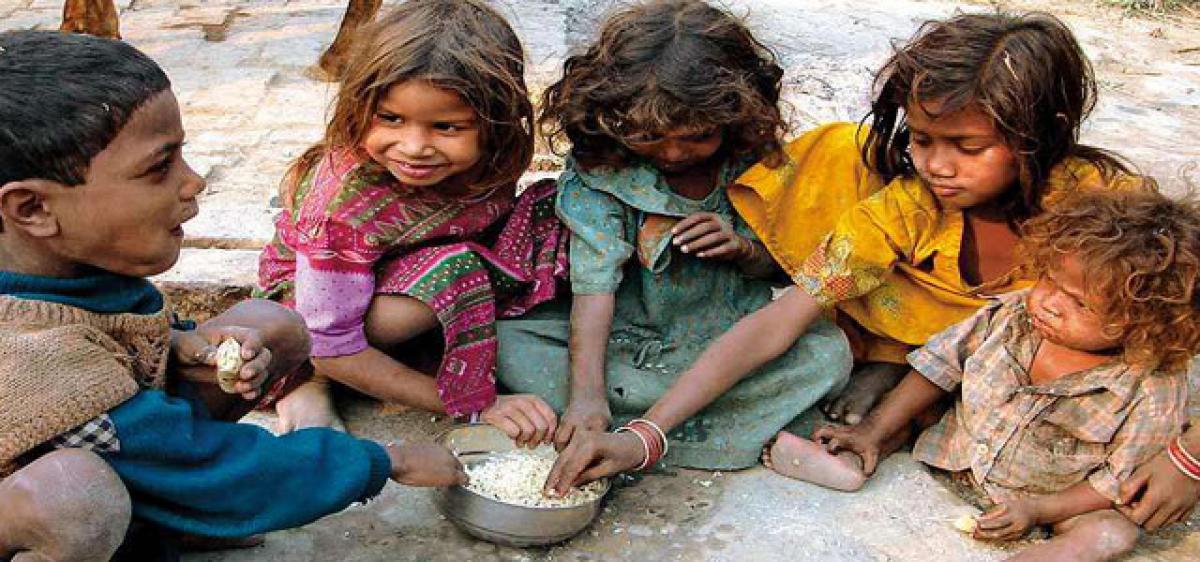

Despite rapid growth and development, an unacceptably high proportion of our population continues to suffer from severe and multidimensional deprivation. It is not as if we are not mindful of this massive development challenge. The need to “end poverty, ignorance, disease and inequality of opportunity” was stressed in speeches during the Constituent Assembly meetings.

It was recognised that “free India would be judged by the way it served the interests of the common people in terms of food, clothing, shelter and social services.” The day we attained Independence, Rajendra Prasad, the country’s first President, asked for a commitment “to create the conditions to enable each individual to develop and rise to their fullest stature, such that poverty, squalor, ignorance and ill-health would vanish, along with any distinction between high and low and between rich and poor.”

Concerns and commitments on reducing, ameliorating and eliminating poverty have been expressed repeatedly at the highest level. For instance, former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh made a commitment to ensure that the “struggle for the removal of chronic poverty, ignorance and disease will register major gains in the Eleventh (five year) Plan”. More recently, a cabinet secretariat press note regarding constitution of the NITI Aayog stated: “Poverty elimination remains one of the most important metrics by which alone we should measure our success as a nation.”

At the turn of the century, the Millennium Development Goals sought to “eliminate extreme poverty and hunger.” Today, the Sustainable Development Goals aim to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere.” Clearly, there is recognition at national and global levels of the importance of reducing or eliminating poverty. Yet, our report card on poverty remains dismal. What have we achieved and what do we need to do to achieve the elusive goal of ending poverty in India?

How many Indians are poor?

In order to address a problem, we must know its size. What is the quantitative measure of poverty in India? What portion of our population is affected by it? The answer to this question may vary depending on the measure we apply.

The proportion of our population living in poverty has declined over time. However, the poverty lines were set low and the decline was not as rapid as expected. Was 27.5 per cent of our population in poverty in 2004-05 or was it 37.2 per cent? If we use the Lakdawala Committee-based poverty line for 2004-05, 27.5 per cent of the population was living in poverty.

If, however, we use the Tendulkar Committee method, 37.2 per cent people were living in poverty. What is the difference between these lines? The Lakdawala Committee-based poverty line was set at Rs 356.30 per capita per month for rural areas and Rs 538.60 per capita per month for urban areas.

Dissatisfaction with previous poverty lines led to the constitution of the Tendulkar Committee, which raised the rural poverty line by Rs 40 per capita per month to Rs 446.68 and the urban poverty line from Rs 90 per capita per month to Rs 578.80. The result was a 10 per cent escalation in the extent of poverty, with 407.2 million people living below this subsistence level poverty threshold.

Regardless of what poverty line we use, it is clear that poverty is a massive problem. If poverty lines are raised to realistic—instead of subsistence—levels, we will find that at least half our citizens are poor and a significant proportion of those who are above the poverty line are vulnerable to poverty. The first step in tackling poverty then, is that we acknowledge the extent of poverty and measure it.

Why anti-poverty schemes failed?

A large number of programmes and schemes have been implemented to directly attack poverty through generating work, providing healthcare, education, nutrition and support to backward areas and vulnerable groups. Although the poverty rate has declined, a large proportion of our population still lives in poverty. There are several reasons for this. While a large number of poverty alleviation programmes have been initiated, they function in silos.

There is no systematic attempt to identify people who are in poverty, determine their needs, address them and enable them to move above the poverty line. There is no commitment by the government to support an individual or a household for getting minimum level of subsistence through any programme or group of programmes.

The resources allocated to anti-poverty programmes are inadequate and there is a tacit understanding that targets will be curtailed according to fund availability. For instance, Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) does not provide the guaranteed 100 days of work in many states.

In another example, the Centre has provisioned Rs 200 per person per month for old age pension, with the understanding that states would add to this amount. But there is a substantial difference in the amount that different states add to the pension. Thus, your old age pension depends on where you live — Rs 200 per month in some states and Rs 1,500 or more in others.

There is no method to ensure that programmes reach everybody they are meant for. While our plans have taken cognisance of the literature on chronic poverty and dynamics of poverty, alleviation programmes and schemes have not used this understanding to address this issue.

To address poverty effectively, people who formulate alleviation programmes need to understand and address chronic poverty and the dynamics of poverty. We know, for instance, that poverty is especially prevalent among certain occupational groups. Casual agricultural labour is the largest group that is stuck in poverty, as per data from the socioeconomic caste census. These are the “working poor,” for whom the State has not been able to secure the right to an adequate means of livelihood. This must be addressed.

Similarly, we know that there is a geographical dimension to poverty—concentration of poverty in certain parts of the country. So there should be renewed focus on the poorest districts: to universalise access in these areas and applying indicators that assess performance-based improvement of the most vulnerable. Poverty has persisted among certain marginalised groups, especially among the Scheduled Tribes.

Hence, the inclusion of tribal girls or women in programmes in the poorest blocks and villages should be used as an indicator of performance. Instead of only estimating the number of poor, we should understand how many people are stuck in poverty and why? What are the factors that explain the persistence of poverty?

How can these be addressed? How many people have moved out of poverty? What enabled them to move out of poverty? Did they manage to stay out of poverty? How many people who were not poor earlier have become poor? What shocks did they suffer that led to their impoverishment?

How can these be prevented from pushing people into poverty? As things stand, many of those living in poverty today will continue to remain poor over time and may pass their poverty to their children. This, combined with the magnitude of the problem, demands that we address the poverty challenge on priority.

By: Aasha Kapur Mehta

(Writer is Professor of economics at the Indian Institute of Public Administration, New Delhi; Courtesy: Down To Earth; http://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/poverty-eradication-why-do-we-always-fail-56927)