The Invisible Heroes

Freshly sown paddy fields are velvety lawns. Farmers are men in dhotis. Villages are places for fancy selfies for the modern generation.

Freshly sown paddy fields are velvety lawns. Farmers are men in dhotis. Villages are places for fancy selfies for the modern generation.

Rural India is that quaint land of colourful people for calendar photos. These perceptions are real and aid in widening the chasm between a rapidly urbanising society and the places where India still lives.

A divide that is perturbing in every aspect - the rural side at a clear disadvantage - but rather glaring in terms of media coverage and movie representation.

Cinema has no place for rural India. And, the battle-scarred farmer who fights against all odds to feed the nation is always a provider, never a protagonist. The hero of this nation is invisible not just to policymakers but also to filmmakers.

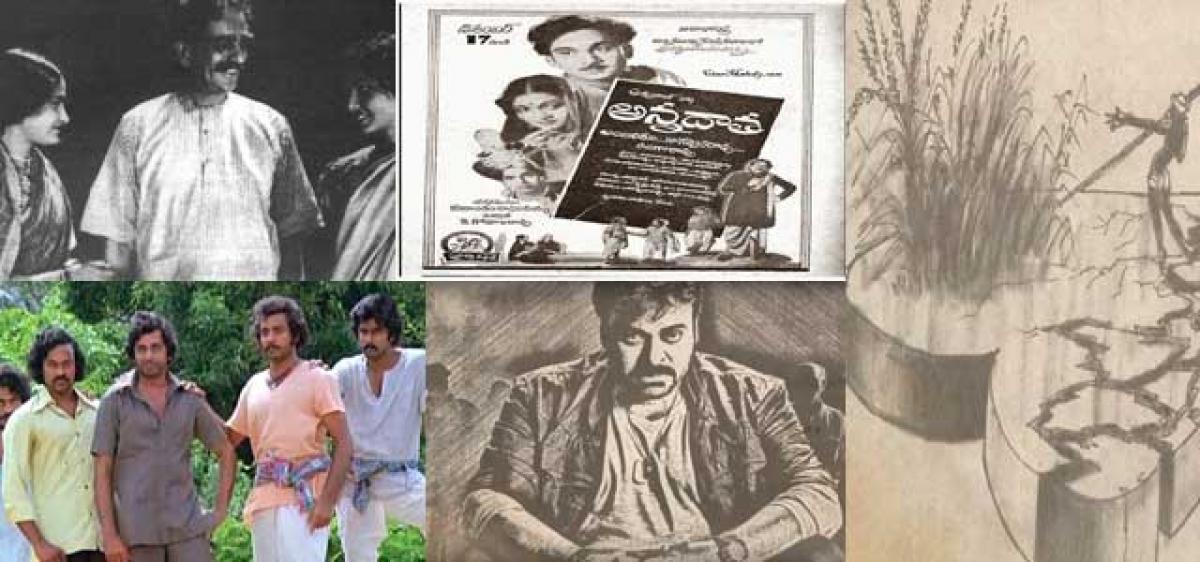

There was indeed a time when Telugu films did reflect social realities. The onset of Telugu movies coincided with the peak of the freedom movement and the struggles of farmers against the Zamindari system were first portrayed in the 1939 film ‘Raitu Bidda’, with a story by stalwarts such as Tripuraneni Gopichand, Tapi Dharma Rao and Vishwanatha Kaviraju and directed by the legendary Gudavalli Ramabrahmam.

Interestingly, it was produced by the Challapalli Maharajah and starred theatre greats such as Bellary Raghava. ‘Annadata’ in 1954, ‘Parivartana’ in 1954, ‘Rojulu Maaraayi’ in 1955 were the other films that had a farmer as the protagonist and starred Akkineni Nageswara Rao and NT Rama Rao.

The late 1950s and 1960s saw a shift in the storyline from an agricultural background though the setting essentially remained rural. The protagonist became a scion of the very Zamindari system that heroes in earlier films fought against, playing farmers.

While Krishna and Sobhan Babu also did many films in the rural setting, the story hardly addressed the occupational facet of a farmer. Krishna, who was probably the most versatile in his generation, did spy films, cowboy films, folk stories and family dramas but his ‘Paadi Pantalu’ of 1975 remains a milestone in the sparse crop of films on agrarian issues.

But his immediate contemporary, Sobhan Babu, took the artsy route, playing the intense lover, poet and family man in films that were mostly in homogenised studio settings.

In later years Balakrishna, Nagarjuna had a few films set in villages while Venkatesh did a couple of films – remakes of Tamil rural films such as ‘Chinarayudu’. Although Nagarjuna had films such as ‘Janaki Ramudu’ in a rural setting, his very recent rural role in ‘Soggade Chinni Nayana’ was once again that of a Zamindar with no reference to agriculture.

Why is rural India not a glamorous place for our filmmakers, except for a random song and dance sequence? "It's all about economics. More precisely, film finances. The investment for Telugu films right from the beginning came only from two districts - Guntur and Krishna. And it has always been rich farmers, who diverted their money to film production.

So, when the finance came from agriculture, the subject matter was rural and the hero a farmer. When the finance came from real estate, the hero became part of a Zamindari system," Srinivas Challa, senior journalist and film analyst, elucidates.

When social conditions changed and more people got educated and migrated to cities, the storylines were changed from rural to city settings, with the protagonist moulded into an educated young man, who studied in the city, attained urbanness and returned home only for a family drama sequence.

From a farmer’s son, he became first the son of the Zamindar, the land owner. Gradually, a transition was made to films that became urban stories, with heroes playing rich businessmen or scions of business tycoons. The only concession that was made in this kind of scripting was the occasional class conflict with protagonist depicted as the champion of the working class.

“All this was the unseen outcome of how the money moved in the society of these two districts. And by 1990s, the focus completely moved away from the rural society. And a farmer’s story wasn’t even considered interesting and for the heroes, playing a farmer was an outdated concept,” sums up Srinivas Challa.

This is an industry that is driven by the imaging of the heroes. The roles are what they choose to play. And the stories are what they want to tell. And as far as the heroes are concerned, the narrative of realistic complexity does not sell anymore. Worse, it may damage their painstakingly built superhuman image.

“Villages are mere nostalgia for the urban masses today. Who wants to live forever in nostalgia? Movies moved from art to business and scene changed from the village to the city.”

What caused this move? With drastic urbanisation from the early 1990s, the dominant paradigm of Telugu cinema was to build larger-than-life tales and personas.

The mandate was to entertain the masses rather than engage them, to showcase the might of the actor rather than the character. And to sell an intoxicating dream rather than represent a reality.

Much has been written about consumerism dictating the direction that cinema had to take. But in the process, cinema forgot an entire slice of life in the very society that it is born out of. Just as more people shunned agriculture as an occupation, so did movies the stories of farmers.

The state of affairs is a reflection of the larger conditions in society. Farmers are no longer players in the way society works; they have merely become hapless producers and faceless consumers. They are just the audiences that B and C Centres teem with and make movies into hits, and heroes into demigods.

“I believe that they have been reduced to a source of collections for the movies. The 1960s were the time when the prime minister himself hailed the farmers and gave a slogan to the country – “Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan”. Kisan was the hero then.

But as we moved towards industrialisation, farmers got neglected not just in policies but also in media,” Suresh Ediga, an NRI-activist, who works with farmers at various levels, rants.

In the 70's and 80's there were still a few movies here and there about land acquisition and farmers’ struggles but now media is all about itself, the people it covers are left behind in the dark, Suresh says.

At this juncture, with offbeat attempts such as ‘Nuvvostanante’…and ‘Srimanthudu’ gently tickling the audiences, Chiranjeevi’s comeback film takes the subject head on and suddenly brings the focus onto a forgotten hero – the farmer.

While critics chuckle at the lofty dialogues in the film about saving the farmer, something the megastar forgot to really address when he had a chance to influence policy as a people’s representative, the film still makes a point.

It manages to etch the portrait of a wretched farmer, beleaguered by issues of Government and corporate dominance. But then, it is not the farmer who is the hero. It is still the megastar.

“I feel ‘Khaidi No. 150’ brought out the sad status of our society, the complete ostrich mindset in which we all particularly live in. And yet, the director has failed to do justice to the story. It is not the hero’s dances and fights that people are supposed to remember when they walk out of the theatre. It should be the farmers’ plight.

The film should remind them of the displacement that Mallanna Sagar, Polavaram and Amaravati brought about. It should remind them about the farmer suicides,” reviews Dr GV Ramanjaneyulu, agricultural scientist and activist.

Films are indeed all about economics, he says, recalling the time they tried to make a short film on farmer issues and suicides but could not convince production houses that farmers are a great subject matter for a film. “They are all part of the same development model that kills the farmers,” Ramanjaneyulu laments.

“When the world globalises, we should localise. That is the norm. Hindi cinema has learned a language different from the Bollywood. But Telugu cinema is still far away from that maturity. Can we ever have a star who talks in rural slang like a Haryanvi or Punjabi hero in Hindi films?” Srinivas says.

A farmer will always be a hero. His heroics may not appeal to the urban poseurs. His struggle will be part of the way the wheels of this nation turn. But, it shall remain invisible. The disappearance of the farmer from the silver screen is indicative of a deeper malaise.

It is the sign of times when entertainment is anxiously cherished and reality an unwanted horror. We do not want misery, only melodrama.

We do not like tears, only titillation. We do not want to know the story behind our plate of food; we want life packaged and off the supermarket shelf. Quickly. Colourfully. Easily.

Those few farmer stories

The number of films that had farmers as the lead characters are a mere handful, even in dozens of films set in a rural milieu.

‘Raitu Bidda’ (1939), directed by Gudavalli Ramabrahmam, starring Bellary Raghava, Tanguturi Surya Kumari et al, ‘Annadata’ (1954), directed by Vedantam Raghavaiah;

‘Parivartana’ ( 1954), directed by Tatineni Prakasa Rao, starring NTR, ANR, Savitri; ‘Rojulu Maaraayi’ (1955), directed by Tapi Chanakya, starring Akkineni Nageswara Rao, Sowcar Janaki; ‘Raitu Kutumbam’ (1972), starring ANR were among the first crop while Krishna's

‘Padipantalu’ (1975) stands out as the one-off film totally based on a farmer's life.

Sobhan Babu had a couple of films in a rural setting and the next generation of stars, Nagarjuna, Venkatesh and Balakrishna chose characters that were merely on a rural fringe.

Chiranjeevi, who takes up the cause of the farmers in his comeback film, played a role that vaguely resembled a farmer in the Seema thriller ‘Indra’, had in his very early films ‘Pranam Khareedu’, ‘Mana Voori Pandavulu’, etc, had roles that were set in rural society.

In the more recent ones, ‘Nuvvostanante Nenoddantaanaa’ featured Siddharth in a storyline that directly tells of a farmer's travails, albeit wrapped in the sugar candy of a love story.

In the non-existent stream called parallel cinema, a couple of brave hearts such as B Narsing Rao and R Narayana Murty attempted to make movies on rural life and its vagaries but the wonderful ‘Maa Bhoomi’ has never found an echo in the mainstream again.

By: Usha Turaga-Revelli