Foretelling: An addiction to prediction

How Rahu Affects Career and Rahu's Potential Benefits – Guidance by Top Astrologer in Toronto’s Acharya Devraj Ji

The jury is still out on such questions as whether astrology is a science or a pseudoscience, and whether its track record justifies the large following it commands. Needless to say, there is no shortage, of detractors, of this rather controversial field. There are those, for instance, who ask how likely it is, that more than half the world, working out to over four hundred million people for each of the 12 signs of the zodiac, are likely to have a similar kind of experience on a given day. Surely, they argue, their horoscopes could not all have put out the same predictions for the day

Vedic astrology, an integral part of the Vedas and India's ancient system of knowledge, is based on the belief that the stars and planets influence the 'karma', or the deeds of human beings and the consequences thereof. Each 'Graha,' or planet, represents an aspect of life, and is ruled by a particular deity. Sage Bhrigu, one of the seven Vedic Sages or 'Sapta Rishis' and called the father of Hindu astrology, was one of the earliest practitioners of astrology. Great personages, such as Aryabhatta and Varahamihira, refined the practice in subsequent times. The version of astrology, common in the western countries, largely owes its origin to ancient Greece, especially Babylon.

Often called the 'science of fate,' astrology, its followers believe, helps understand such aspects, of future endeavours of people, as moving into a new home, a business venture or even government decisions. It was also used in the past for predicting the results of battles. Another connected practice is that of divination with cowrie shells, which is prevalent, particularly among the Yoruba people of West Africa. The oldest spiritual practice in the world, it is a powerful technique for connecting to the wisdom of ancestors, spirits and deities. It is also believed that a proper reading of the seven lines on the forehead of a person can also help predict such aspects.

The jury is still out on such questions as whether astrology is a science or a pseudoscience, and whether its track record justifies the large following it commands.

Needless to say, there is no shortage, of detractors, of this rather controversial field. There are those, for instance, who ask how likely it is, that more than half the world, working out to over four hundred million people for each of the 12 signs of the zodiac, are likely to have a similar kind of experience on a given day. Surely, they argue, their horoscopes could not all have put out the same predictions for the day. Another moot point is why astrology is based on the time of birth of an individual, rather than the moment of conception. Childbirth, after all, is now known to be the culmination of over nine months of complex processes inside the womb. Many aspects of a child's personality are known to have been set long before birth.

The detractors also point out that, although their claims are not backed by any evidence, horoscopes continue to be published in newspapers. What is worse, no disclaimer is added by the editorial staff to dissociate the newspaper from the views, nor firm facts offered in support of the predictions made therein. They find it truly amusing that, in 1988, First Lady Nancy Reaganof USA felt the need to consult an astrologer to arrange her husband's campaign schedule. Also, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has, in a recent blog post, described astrology as 'something else,' and not a science.

Palmistry a sister field, is the practice of foretelling one's future by studying the palm of a person. Reportedly, it finds its origin in a book, written around 500 BCE, by the legendary Sage Valmiki and, thereafter, spread to China, Tibet and parts of Europe. Subsequently, it made inroads into Greece. Aristotle, the Greek philosopher, is said to have discovered a treatise on the subject, which he presented to Alexander the Great. Alexander reportedly evinced great interest in examining the character of his officers, by analysing the lines in their hands.

Christianity, and Islam, both adopted a somewhat ambiguous attitude towards palmistry. While the former adopted a stop-go approach to the field, only Sufism of Islam found no reason to discourage it. The Shias, on the other hand, condemned it as blasphemy. The Sunni sect, however, allowed the preaching of astrology in an abstract form.

Palmists, or hand readers, are popular in practically every country of the world, the often conflicting interpretations of the lines of the palm, and the absence of a scientific foundation, for their readings, notwithstanding. A practice of the same genre is numerology, an ancient study that draws meaning from numbers, letters, and their combinations. Many readers would surely have heard of Cheiro and his book of numbers. The author, whose original name was William de Hamon, studied in depth the lines of the palm, and their meanings, and evolved a discipline based on the principle that numbers can make one predict the future accurately.

The 'Nadi Grantham's, books of subtle knowledge, are regarded as repositories of knowledge of the future, said to have been recorded by the Sapta Rishis, more as records of life and information, rather than as predictions. This columnist recollects his sister and brother-in-law, consulting an elderly saintly person, to read the relevant portion of those books, as a measure of reassurance, about what the future held in store for their son Sitaram Yechury. Sitaram had, at that time, begun to dabble in politics and had even got into serious trouble with the powers that be.

Many of us will have encountered persons possessing an uncanny ability to obtain information about an object, a person, location, or an event, through extra sensory perception or ESP. Known as clairvoyants, they possess the extraordinary gift of perceiving events, whether past, present, the future, even from a great distance. Belonging to a somewhat the category are soothsayers, who can predict the future, using magic, intuition, or intelligence, also known as diviners.

Let us keep aside, for a moment, the question of the efficacy, and trustworthiness, of prophesying and forecasting, We see from history that several great scientists and economists, among others, were able to imagine years and decades, if not centuries, in advance the likelihood of future happenings. The shape of things to come, if you like, to borrow the title of the famous book by H.G. Wells. Neil Armstrong, for example, may only have taken the first 'giant leap for mankind' in 1969. But Jules Verne in his book, 'From the Earth to the Moon,' not only predicted, way back in 1865, that man would land on the moon, but even set the launching event in Florida, now the site of Kennedy Space Centre.

A well-developed discipline that has come into being in somewhat recent times is called futurology. A systematic and critical treatment of problems related to future studies, it was first introduced in 1943 as a concept in a book by Ossip K. Flechtheim, entitled 'Teaching in the Future'. It concerns itself, essentially, with imagining in advance how people will live, work and communicate in the future.

In a somewhat related area, almost in the twilight zone, between science and superstition, lies the ancient habit of interpreting celestial signs such as comets and shooting stars.

The Greeks and the Romans believed that the appearance of comets, meteors and meteor showers was portentous, and a sign of something good or bad, that had either happened or was likely to happen. In 44 BCE, the appearing of a comet was interpreted as a sign of deification of Julius Caesar, following Caesar's murder. Likewise, and in more recent times, Mark Twain, the legendary American humanist, was quoted by his biographer Albert Paine as having said that he had come in touch with Halley's Comet in 1835, and, with the comet coming again, in 1910, expected to go out with it. And Twain, as a matter of fact, did!

Thus, the credibility of astrology, together with that of its related fields of palmistry and numerology, has neither been decisively established, nor did otherwise.

The situation, however, is not confined to the times in which we live. There is a story, probably apocryphal, about the great king Krishnadevaraya, who had summoned his royal astrologer to fix up a 'Muharat' for an invasion he was planning. During the consultation, Appaji, otherwise known as 'Thimmarasu,' the wise counsellor on whom Krishnadevaraya depended heavily, playfully asked the wise consultant how long he expected to live. After a moment's contemplation, the astrologer confidently predicted that he would live for at least 20 more years.

Then, upon a signal from Appaji, a soldier, waiting in a nearby corridor shot the astrologer dead with an arrow. It is indeed intriguing that, hundreds of years later, the dilemma continues to challenge humanity.

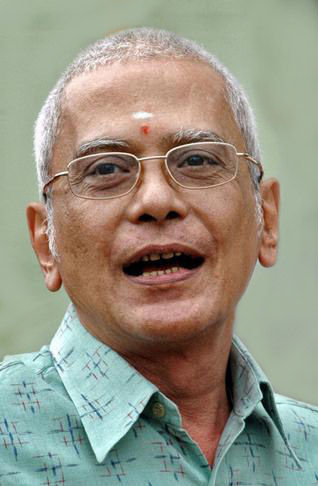

(The writer is formerly Chief Secretary, Government of Andhra Pradesh)