CCMB researchers discover key role of protein agility in binding to different molecular partners

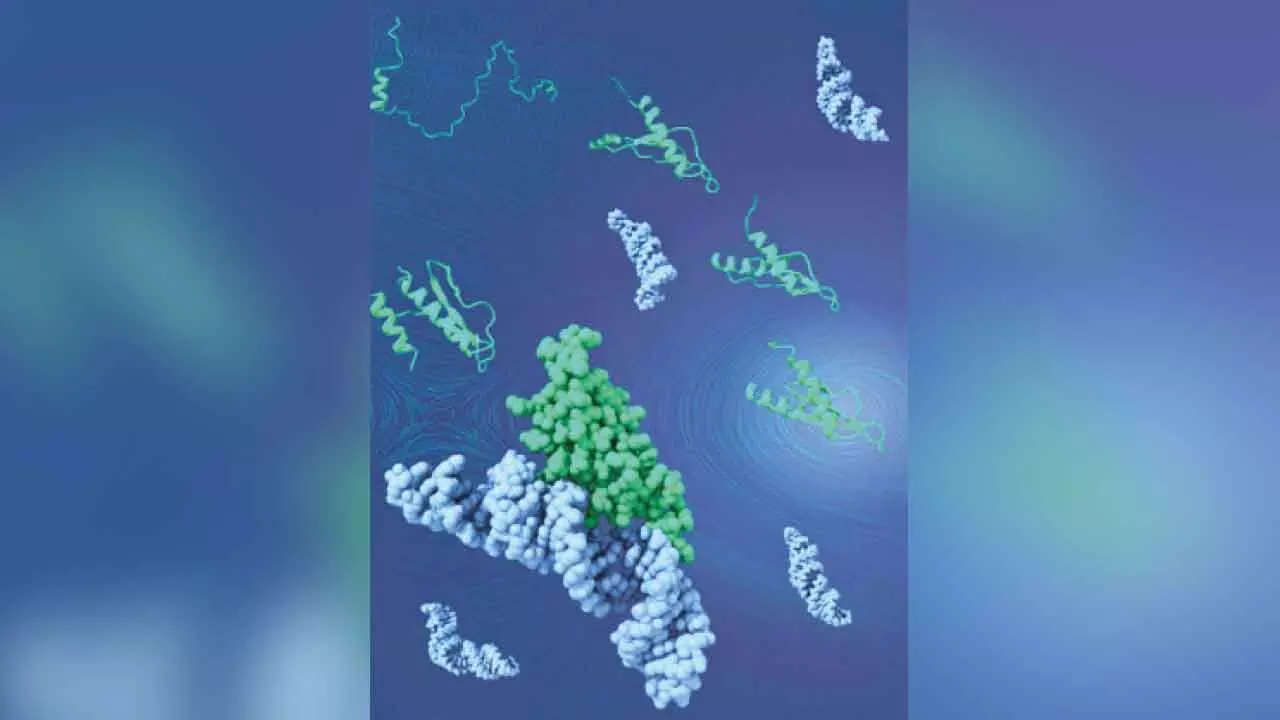

Hyderabad: Scientists at the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) have recently made a significant discovery: proteins can perform multiple functions by temporarily changing their shape, not only based on their fixed three-dimensional structure but also through their flexibility.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, reveals that two structurally identical plant proteins exhibit different substrate specificities, allowing them to recognise distinct substrates. The key difference is that one of the proteins is more flexible than the other.

This enhanced flexibility enables it to bind to various types of RNA molecules, as the protein can dynamically rearrange its structure to align with the shape of its partner molecules.

This property is crucial for gene regulation. Using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and advanced computational methods, researchers identified transient protein structures that constitute only 1 per cent of the total protein. These structures, which briefly change shape, play a vital role in recognising different RNA forms. “We demonstrated that a protein’s ability to change shape slightly is just as important as its stable structure,” said lead author Dr Mandar V Deshmukh.

Through these transient dynamic states, proteins can function efficiently in the complex conditions of the cellular environment, helping organisms to regulate their genes properly under changing circumstances. This discovery could lead to revolutionary advancements in drug design and the improvement of plant traits in the future.”

The study also revealed that changes in a few amino acids in non-active site residues of a protein can result in significant functional differences.

This underscores the importance of comprehensively studying both structure and dynamics, particularly in the development of drug target proteins. “The ability of some proteins to perform multiple functions, known as functional promiscuity, reflects one of Nature’s originalities,” noted Debadutta Patra and Jaydeep Paul, joint first authors of the study.

The research highlights how plants precisely control RNA processing using fewer proteins and without the need for an adaptive immune system. Scientists believe this study could pave the way for new discoveries in medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.