Live

- Per capita availability of fruits, vegetables increases in India

- FII buying reaches Rs 22,765 crore in Dec as economic growth stays resilient

- National Energy Conservation Day 2024: Date, Importance, and Easy Ways to Save Energy

- Gastronomic trouble: After 'disappearing' samosas Himachal CM in row over red jungle fowl

- Meaningful dialogue a priceless jewel of democracy: Jagdeep Dhankhar

- CM Revanth Reddy Advocates for Gurukuls as Talent Development Centers

- Zepto’s expenses surge over 71 pc in FY24, losses at Rs 1,248 crore

- Tim Southee matches Chris Gayle's six-hitting record in his farewell Test

- AP Mnister Ponguru Narayana Inspects Highway Connectivity Roads to Amaravati

- Reduced inflow: Water levels in Chembarambakkam, Poondi reservoirs drop

Just In

In Erice, near the western coast of Sicily, a twelfth—century Norman fortress rises two thousand feet above the ground on a furl of rock. Viewed from afar, the fortress seems to have been created by some natural heave of the landscape, its stone flanks emerging from the rock face of the cliff as if through metamorphosis.

In Erice, near the western coast of Sicily, a twelfth—century Norman fortress rises two thousand feet above the ground on a furl of rock. Viewed from afar, the fortress seems to have been created by some natural heave of the landscape, its stone flanks emerging from the rock face of the cliff as if through metamorphosis.

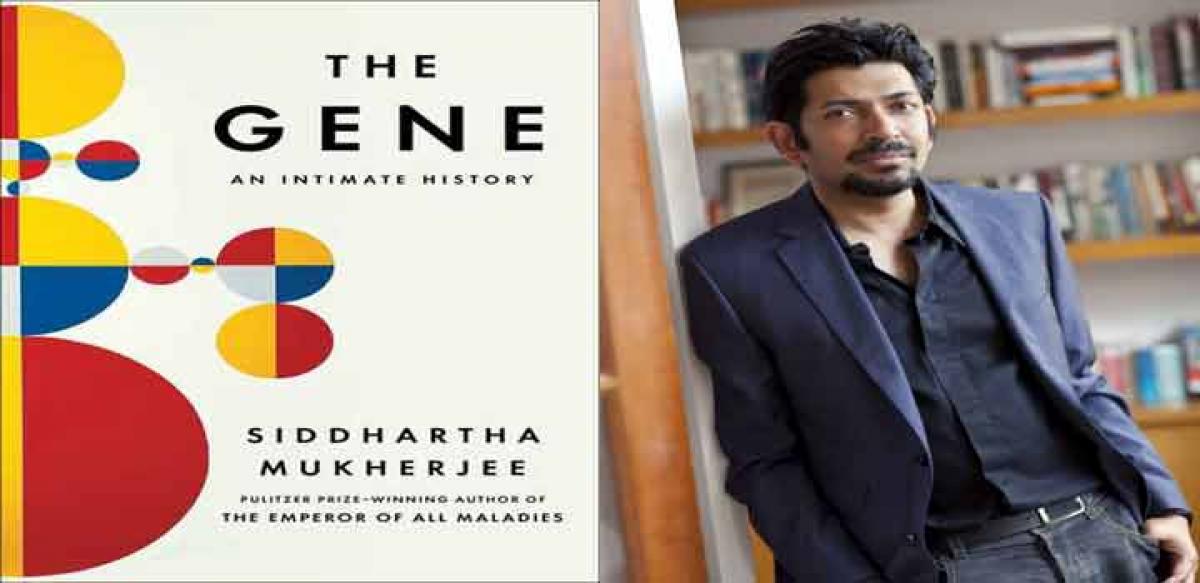

Siddhartha Mukherjee’s ‘The Gene’ is the story of the quest to decipher the master-code that makes and defines humans. The latest book of Siddhartha Mukherjee, author of ‘The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer’, and winner of the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in general non-fiction category, ‘The Gene’ is the story of the birth, growth, and future of one of the most powerful and dangerous ideas in the history of science: the ‘gene’, the fundamental unit of heredity, and the basic unit of all biological information.

Siddhartha says – Three profoundly destabilising scientific ideas ricochet through the twentieth century, trisecting it into three unequal parts: the atom, the byte, and the gene. Each is foreshadowed by an earlier century, but dazzles into full prominence in the twentieth.

Each begins its life as a rather abstract scientific concept, but grows to invade multiple human discourses – thereby transforming culture, society, politics, and language. The extract from the book refers to Nobel Prize winning American biochemist Paul Berg, and his efforts to find possible mechanisms to control and regulate gene cloning during the 1970s.

The Erice Castle, or Venus Castle, as some call it, was built on the site of an ancient Roman temple. The older building was dismantled, stone by stone, and reassembled to form the walls, turrets, and towers of the castle. The shrine of the original temple has long vanished, but it was rumored to be dedicated to Venus. The Roman goddess of fertility, sex, and desire, Venus was conceived unnaturally from the spume spilled from Caelus’s genitals into the sea.

In the summer of 1972, a few months after Paul Berg had created the first DNA chimeras at Stanford, he traveled to Erice to give a scientific seminar at a meeting. He arrived in Palermo late in the evening and took a two-hour taxi ride toward the coast. Night fell quickly when he asked a stranger to give him directions to the town, the man gestured vaguely into the darkness where a flickering decimal point of light seemed suspended two thousand feet in the air.

The meeting began the next morning. The audience comprised about eighty young men and women from Europe, mostly graduate students in biology and a few professors. Berg gave an informal lecture—“a rap session?” he called it—presenting his data on gene chimeras, recombinant DNA, and the production of the virus-bacteria hybrids.

The students were electrified. Berg was inundated with questions, as he had expected—but the direction of the conversation surprised him. At Mertz’s presentation at Cold Spring Harbor in 1971, the biggest concern had been safety: How could Berg or Mertz guarantee that their genetic chimeras would not unleash biological chaos on humans?

In Sicily, in contrast, the conversation turned quickly to politics, culture, and ethics. What about the “spectre of genetic engineering in humans, behavior control?” Berg recalled. “What if we could cure genetic diseases?” the students asked. “[Or] program people’s eye color? Intelligence? Height? . . . What would the implications be for humans and human societies?”

Who would ensure that genetic technologies would not be seized and perverted by powerful forces—as once before on that continent? Berg had obviously stoked an old fire. In America, the prospect of gene manipulation had principally raised the specter of future biological dangers. In Italy—not more than a few hundred miles from the sites of the former Nazi extermination camps—it was the moral hazards of genetics, more than the biohazards of genes, that haunted the conversation.

That evening, a German student gathered an impromptu group of his peers to continue the debate. They climbed the ramparts of the Venus Castle and looked out toward the darkening coast, with the lights of the city blinking below Berg and the students stayed up late into the night for a second session, drinking beers and talking about natural and unnatural conceptions — “the beginning of a new era . . . [its] possible hazards, and I the prospects of genetic engineering?

In January 1973, a few months after the Erice trip, Berg decided to organize a small conference in California to address the growing concerns about gene—manipulation technologies. The meeting was held at the Pacific Groves Conference Center at Asilomar, a sprawling, wind—buffeted complex of buildings on the edge of the ocean near Monterey Bay, about eighty miles from Stanford.

Scientists from all disciplines—virologists, geneticists, biochemists, microbiologists—attended. ‘Asilomar If’ as Berg would later call the meeting, generated enormous interest, but few recommendations. Much of the meeting focused on biosafety issues. The use of SV40 and other human viruses was hotly discussed. “Back then, we were still using our mouths to pipette viruses and chemicals,” Berg told me.

Berg’s assistant Marianne Dieckmann once recalled a student who had accidentally flecked some liquid onto the tip of a cigarette (it was not unusual, for that matter, to have half-lit cigarettes, smoldering in ashtrays, strewn across the lab). The student had just shrugged and continued to smoke, with the droplet of virus disintegrating into ash.

The Asilomar conference produced an important book, Biohazards in Biological Research, but its larger conclusion was in the negative. As Berg described it, “What came out of it, frankly, was the recognition of how little we know.” Concerns about gene cloning were further inflamed in the summer of 1973 when Boyer and Cohen presented their experiments on bacterial gene hybrids at another conference.

Published with permission from Penguin Books India

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com