Live

- MacBook Air M3 Hits Lowest Price in India: Find Details

- High Court Adjourns Hearing on Allu Arjun's Petition to 4 PM

- Pawan Kalyan praises Chandrababu Naidu at Swarnandhra Vision 2047 document launch

- Chirec International looks to transform education with Chirec 2.0 vision

- Telangana CM Revanth Reddy Responds to Allu Arjun's Arrest in Delhi

- Uddhav Thackeray to PM Modi: Pay attention to Bangladesh, act to end Hindus’ misery

- Allu Arjun Arrested: KTR Reacts on X, Calls Arrest Unfair

- Bold steps by Modi govt in reviving Indian heritage, culture: Union Minister

- What are the charges against Allu Arjun: Understanding the Charges Against Him

- Allu Arjun Objects to Arrest Procedure, Requests Breakfast and Change of Clothes

Just In

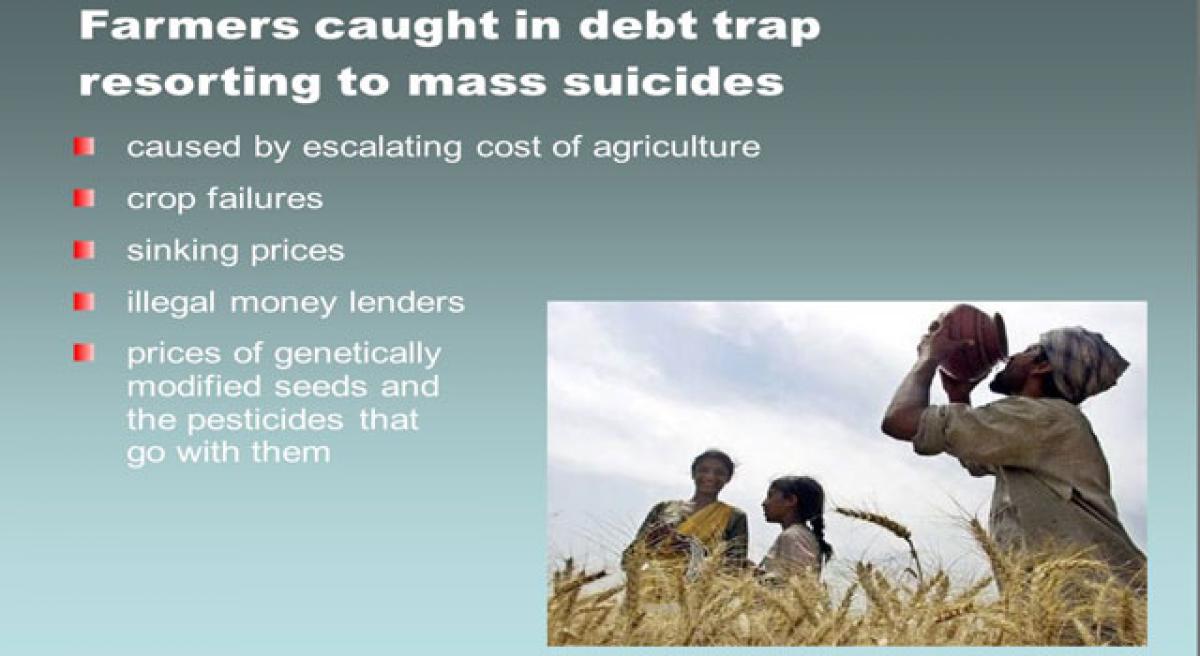

Notwithstanding the fact that the government is all set to waive-off billions of dollars in farmer loans, the actually distressed class among them will have no respite from their misery. They owe their debts to money lenders whereas the government waiver applies only to formal credit.

Notwithstanding the fact that the government is all set to waive-off billions of dollars in farmer loans, the actually distressed class among them will have no respite from their misery. They owe their debts to money lenders whereas the government waiver applies only to formal credit.

Almost every farmer in India’s massive rural swathes is tethered, in one way or another, to the sahukar, the Indian variety of the money lender, the ubiquitous, ravenous loan shark. For centuries, money lenders have monopolised rural Indian credit markets. Families have lost land, farmers have been asked to prostitute their wives to pay off debts, and, when all else has failed, they have tied the noose to end their misery.

An inescapable cycle of debt continues to grip rural India, particularly its farming class. Yet the public image of menacing debt collectors does not reflect the actual plight of India’s three million farmers. Money lenders have been around for generations, but their business has boomed ever since India’s economic priorities shifted, with globalisation, from agriculture to industry.

The arrival of high-cost seeds and pesticides and the attraction of bumper harvests have added to the debts. In farm belts money lenders operate under the guise of farm input sellers. In Maharashtra, farmers’ dependence on private money lenders has shown a steep rise at 40 per cent in the past one year. The total amount of loans disbursed by private money lenders was Rs 1,254,97 crore. Compared to 2015 statistics, the total amount disbursed thus has risen by Rs 358.63 crore.

According to the All India Debt Investment Survey 2012, nearly 48% farmers across the country took loans from informal sources such as moneylenders and landlords. The number had risen from 36% in 1991 and 43% in 2001. Among farmers who owned land parcels smaller than 0.1 hectares, 85% had pending loans from such informal finance sources.

While these small farmers pay exorbitant interest, affluent famers get subsidised credit. The government’s interest subvention (subsidy) scheme for farmers provides credit at subsidised interest rate of 7 per cent and for prompt re-payers at 4 per cent. Yet, the public image of menacing debt collectors does not convey the sentiments of millions of farmers.

The rapacious money lender, who plugs the huge gaps in credit supply in a hassle free process, is an inalienable part of a rural family. He is the first port of call in a distress situation, and is also the man they can turn to in times of need. For most villagers there is no life without him.

Farming distress has attracted a new breed of money lenders. Anyone with some disposable cash from shopkeepers, government officials, and policemen to village teachers now lends in the hope of making a killing. They are willing to extend credit, but at highly extortionate rates sometimes exceeding 50 per cent, which keeps borrowers in lifelong penury.

Loan sharks also do not ask questions regarding your borrowing history, meaning that the defaulters find a safe haven with them. Then there are those who are seeking to hide because of the shame of borrowing. Seeing as the transactions are quick and the requirements minimal, the moneylenders might seem like the perfect solution for those seeking a quick fix. Their customers agree that they are a working solution as long as you do not default on your loan.

A current of dread runs through the country’s suicide-ravaged farmlands as their debts pass from husband to widow, from father to children. Most villages are locked into a bond with village money lenders an intimate bond, and sometimes a menacing one. Popular cinema and classic literature tell many pathos-filled narratives of India’s poor caught in that karmic cycle of poverty. Those stories inevitably end in tragedy.

Farmers who fall into the money lending trap find themselves locked in a white-knuckle gamble, juggling ever-larger loans at usurious interest rates, in the hope that someday a bumper harvest will allow them to clear their debts so they can take out new ones. This pattern has left a trail of human wreckage.

Despite legions of committees and reports that have outlined ways of replacing moneylenders through stepping up institutional credit, the moneylender still remains the backbone of the rural financial system. It is a bitter truth which we have to swallow. The picture which Nobel Laureate Gunnar Myrdal presented in his memoirs Asian Drama almost five decades ago remains the same, despite gigantic efforts from both the private and public sector in bringing large swathes of people into the folds of formal finance.

“When the money lender sees that he can benefit from the default of a debtor he becomes an enemy of the village economy,” he wrote. “By charging exorbitant interest rates or by inducing the peasant to accept larger credits than he can manage, the money lender can hasten the process by which the peasant is dispossessed.” (INFA)

By Moin Qazi

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com