A desanctified, usable Gandhi

During the last two decades, Tridip Suhrud has emerged as a vital bridge between the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century world of Gujarati literature and culture—from within which Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi emerged—and the global fraternity of scholars who find in Gandhi a voice

During the last two decades, Tridip Suhrud has emerged as a vital bridge between the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century world of Gujarati literature and culture—from within which Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi emerged—and the global fraternity of scholars who find in Gandhi a voice that defies the seductive mix of the enlightenment values and a utopic, urban-industrial world to project an altogether different vision of a desirable society.

In that alternative vision, there is a built-in admission that the enlightenment might have made some significant contributions to human civilization but the utopic vision, which the enlightenment projects, has little or nothing to say about the central problem humanity faces today— massive, organized, structural and, one might add, ‘scientized’ violence—towards fellow humans, living nature and future generations that are supposed to inherit the earth.

That quasi-nihilistic violence, which in the twentieth century took a toll of roughly 225 million lives in only genocides, has two crucial components. First, the brutalization that in many societies have taken an epidemic form and, second, the cultivation of political terror without which—one of the protagonists of the French Revolution, Maximilien Robespierre, believed—virtue was helpless.

Like many others, Suhrud rediscovered Gandhi after the emergency and the suspension of civil rights in India in the 1970s. That discovery is part of a larger movement that sees Gandhi as a serious thinker, whose heritage can no longer be left at the mercy of two kinds of admirers who have played an important role in retailing Gandhi earlier.

The first kind venerates him as a saint who must be shelved, because it will be unfair to drag him into the dirty, violent, corrupt world of everyday politics. Talking of this Gandhi, poet Umashankar Joshi once rather sharply reminded philosopher and thinker Ramchandra Gandhi at a seminar that

saints in India were a dime a dozen; Gandhi was unique in that he was one saint who was willing to live in the ‘slum of politics’.

Joshi added that he had borrowed his words from historian Arnold Toynbee who, after the assassination of Gandhi, had said in an homage, ‘Henceforth mankind will ask its prophets, “Are you willing to live in the slum of politics?” ‘Second, there are those who see Gandhi as only a practical visionary whose political and social interventions were either from Indian traditions or ex nihilo, that is, from nowhere. Hence, these admirers consider any serious intellectual engagement with him either a waste of time or an attempt to mislead the present generation of Indians away from the real Gandhi.

There is a touch of vulgarity in this stereotype of Gandhi, and it has become now a political ploy to say that Gandhi was all about doing, not thinking or researching. Such a stance has helped the likes of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar to claim that not only was Gandhi anti-science and superstitious, but ignorant of modern European political theory. My sporadic encounters with Gandhi over the last fifty years prompts me to propose that, among the great freedom fighters and political and social reformers of twentieth-century India, Gandhi was arguably the best acquainted with the dissenting political thinkers and scholars of the West who tried to break radically with the Dionysian self of the European civilization.

The three persons Gandhi called his intellectual gurus were all Western—Leo Tolstoy, Henry David Thoreau, John Ruskin—and, perhaps we may now add, Ralph Waldo Emerson as the fourth. And Gandhi was in excellent touch with movements that were fighting racism, colonialism and for what we now might call feminism, human-scale technology and environmental justice in other parts of the world. Not surprisingly, the Sri Lankan Gandhian, T.K. Mahadevan, whose book Dvija was rediscovered during the emergency, claimed that Gandhi seriously took to the street only twice in his life; the rest of the time he was thinking and writing.

Gandhi’s ninety-seven-volume Collected Works endorses Mahadevan, not his critics. It is in this context that we must judge Tridip Suhrud’s efforts to bring the power and the complexity of Gandhi’s thought to this generation of Indian intellectuals. Probably Suhrud’s first majestic effort along these lines was his much-acclaimed, four-volume English translation of Narayan Desai’s massive four-volume Gujarati biography of Gandhi, My Life Is My Message, later to become the basis of Desai’s moving series of storytelling, Gandhikatha, in riot-ravaged Gujarat in the first decade of this century.

Desai took Gandhikatha not only to small towns and villages of Gujarat but to different parts of India and even to the United States and was invited to take it to Bangladesh when death intervened. Suhrud’s second major venture was the translation of Chandulal Bhagubhai Dalal’s perhaps unintentionally moving biography of Harilal, Gandhi’s prodigal eldest son. It was published as Harilal Gandhi: A Life, with a marvellous brief foreword by Ramchandra Gandhi, which in two pages provides a brilliant, refreshingly new perspective on the critical role Harilal unwittingly played in his father’s life as both a seductive anti-self and an unacknowledged critical-moral presence. This book and its suggestive foreword must be read by anyone trying to enter the inner life of Mohandas Gandhi.

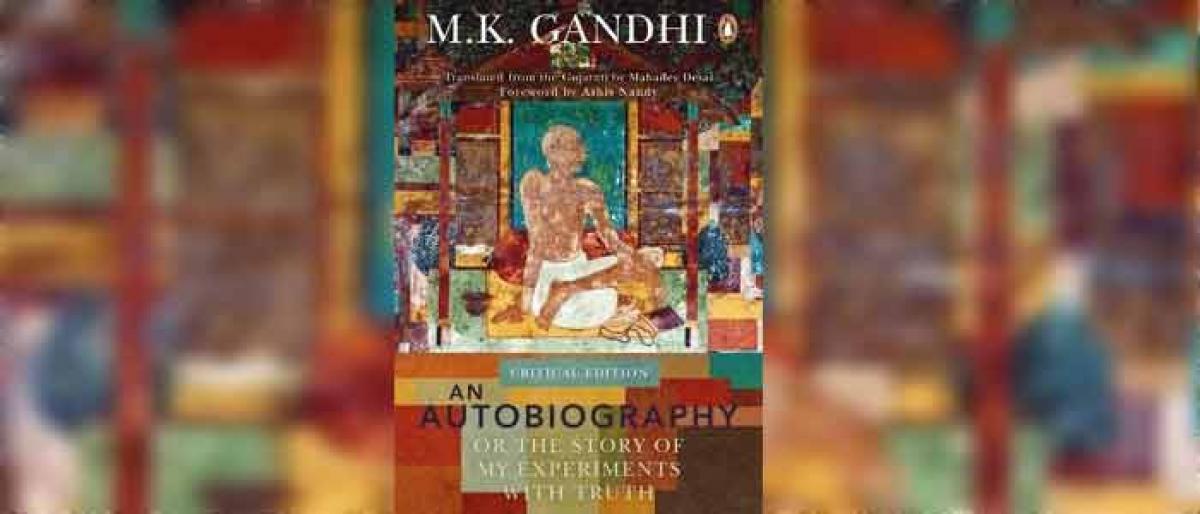

The predecessor of the present book was a joint venture of Suresh Sharma and Tridip Suhrud—an annotated, critical edition of Hind Swaraj. It can be considered a companion volume to this, an annotated, critical edition of Gandhi’s autobiography. The reader will be able to read the autobiography not only as it stands in English but also get some flavour of the Gujarati version and should be able to make a fair guess about the author’s intentions, the translator’s hesitations and ambivalences and, perhaps, even about the tonal differences between the Gujarati and English versions.

Suhrud is an excellent, non-intrusive guide, but he also keeps more than enough space for you to draw your own conclusions and differ violently with his version of truth. (Indeed, this foreword, too, differs at some points from Suhrud’s more diffident reading of his own project, as reflected in his less-known book, Reading Gandhi in Two Tongues and Other Essays.)

On second thoughts, the present book is one that mediates between not merely Gandhi’s time and ours, but also indirectly between Gandhi’s global vision and an over-Indianized, venerated but de-radicalized Gandhi—caught in a spider’s net called Indian politics.

Extracted with permission.