Live

- Over 7,600 Syrians return from Turkiye in five days after Assad's downfall: minister

- Delhi BJP leaders stay overnight in 1,194 slum clusters

- Keerthy Suresh and Anthony Thattil Tie the Knot in a Christian Ceremony

- AAP, BJP making false promises to slum dwellers for votes: Delhi Congress

- 'Vere Level Office' Review: A Refreshing Take on Corporate Life with Humor and Heart

- Libya's oil company declares force majeure at key refinery following clashes

- Illegal Rohingyas: BJP seeks Assembly session to implement NRC in Delhi

- Philippines orders full evacuation amid possible volcanic re-eruption

- Government Prioritizes Welfare of the Poor, says Dola Sri Bala Veeranjaneyaswamy

- Two Russian oil tankers with 29 on board damaged due to bad weather

Just In

Occurrence of the unexpected and the unlikely doesn\'t only work for literary genres like horror, and mystery, let alone fantasy and science fiction, but comedy too. Although much of comedy\'s effect is from the commonplace represented in a way that evokes humour, sometimes something startlingly incongruous works wonders - a comic \'Theatre of the Absurd\', where certainties disappear, and the sublime

Occurrence of the unexpected and the unlikely doesn't only work for literary genres like horror, and mystery, let alone fantasy and science fiction, but comedy too. Although much of comedy's effect is from the commonplace represented in a way that evokes humour, sometimes something startlingly incongruous works wonders - a comic 'Theatre of the Absurd', where certainties disappear, and the sublime and the ridiculous exist side by side.

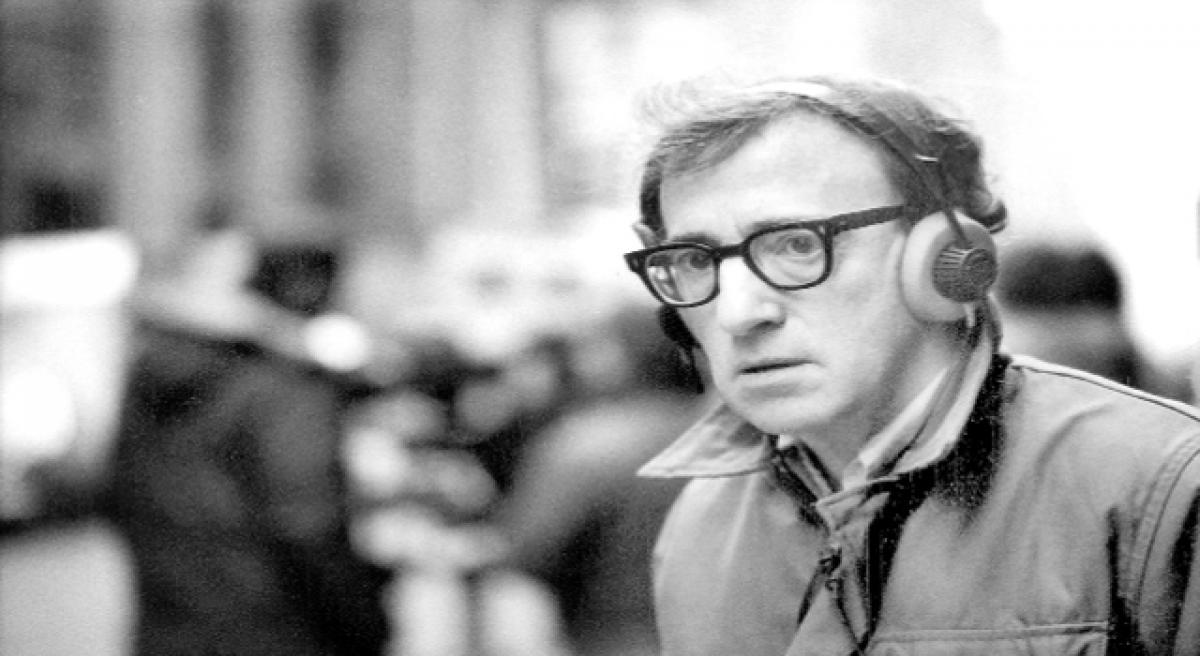

And Woody Allen is a leading practitioner of that. Much feted for his quirky films (where he wrote the screenplays too), usually featuring nerdy and neurotic characters, and exploring love, relationships and other facets of the human condition, Heywood 'Woody' Allen (b. 1935) began his career by writing jokes and scripts for stand-up comedians and TV in the 1950s. He then became a stand-up comedian himself, before graduating to plays and then films - but that is another story.

As a writer, he was hugely successful, both in quantity and quality. Inspired by humorists like SJ Perelman, his short pieces for various magazines display the same traditional themes of mischievous parody, nuanced irony, wry misadventures, playful inventiveness and the frankly ridiculous.

Collections of these, published as ‘Getting Even’ (1971), ‘Without Feathers’ (1975), ‘Side Effects’ (1980) and ‘Mere Anarchy’ (2007) prove that besides his cinematic accomplishments, he also occupies a hallowed place in the annals of humour, besides luminaries like Jerome K Jerome, PG Wodehouse, Douglas Adams and Kurt Vonnegut.

It is a dazzling display of comical literary pyrotechnics, with a wide array of topics and techniques rarely repeated. ‘Getting Even’ opens with ‘The Metterling Lists’, where Allen seeks to explain the fictional philosopher through the first volume of his just published laundry lists – it has to be read to be believed.

‘My Philosophy’ is what he develops when bed-ridden for a month after "my wife, inviting me to sample her very first souffle, accidentally dropped a spoonful of it on my foot, fracturing several small bones", and includes aphorisms like "Eternal nothingness is OK if you're dressed for it" and "Not only is there any God, but try getting a plumber on weekends".

For chess fans, there is "The Gossage-Vardebedian Papers" or a series of letters between the eponymous characters playing a game over mail, but both suspecting the other is cheating. In one, Gossage tells his friend his move is impossible "bound as we are to rules established by the World Chess Federation and not the New York State Boxing Commission". Other pieces span psychoanalysts, revolutionaries, rabbis, gangsters and even Count Dracula.

"Without Feathers" is more stylistically diverse, featuring among others "Selections from the Allen Notebooks" ("Had coffee with Melnick today. He talked to me about his idea of having all government officials dress like hens"), and "Explaining Psychic Phenomena” (where topics include a clairvoyant Greek psychic "who could concentrate on a person's face and force the image to come out on a roll of ordinary Kodak film although he could never seem to get anybody to smile").

‘A Guide to Lesser Ballets’ has, among others, ‘Dmitri’, which opens at a carnival with food and rides, while "many people in gaily coloured costumes dance and laugh, to the accompaniment of flutes and woodwinds, while the trombones play in a minor key to suggest that soon the refreshments will run out and everybody will be dead", and ‘The Spell’, the tragic story of a prince who falls in love with a woman who is half a swan "unfortunately divided lengthwise".

‘Fabulous Tales and Mythical Beasts’ tells us about beings like the "nurk" - "a bird two inches long that has the power of speech but keeps referring to itself in the third person, such as 'He's a great little bird, isn't he?'" and the "great roe", a beast with "the head of a lion and the body of a lion, though not the same lion", whose appearance "usually precedes a famine or news of a cocktail party".

In ‘A Brief, Yet Helpful, Guide to Civil Disobedience’ we learn governments can break hunger strikes by sound trucks saying "Umm... what nice chicken-umm... some peas-umm", "Slang Origins" explaining terms like "the cat's pajamas", "to beat the band" - which "originated from the custom of attacking with clubs any symphony orchestra whose conductor smiled during Berlioz" and only came to end when in one New York performance, "the entire string section stopped playing and exchanged gunfire with the first ten rows" and much, much more.

The first three books, collected in omnibus ‘Collected Prose’ (Picador) freely available here, are for you if you like such zany humour. But don't read it in public - your frequent guffaws and gusts of laughter might leave those around concerned at your sanity.

By: Vikas Datta

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com