The Terror Trail

Mubaraka (congratulations),’ an excited caller exclaimed on the phone. The call was received in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and was made from Karachi, in Pakistan. This call, just a day after the deadly attacks, was one among the thousands of calls intercepted by the Indian Intelligence Bureau (IB).

Mubaraka (congratulations),’ an excited caller exclaimed on the phone. The call was received in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and was made from Karachi, in Pakistan. This call, just a day after the deadly attacks, was one among the thousands of calls intercepted by the Indian Intelligence Bureau (IB).

The mission had been accomplished and a congratulatory message was in order. Another call traced by the central agencies directed the police to a public call office (PCO) in Juhu, Mumbai’s posh waterfront suburb. This was not a work call; it seemed to be a personal one as the voices were filled with emotion. The police recorded the call, which was a hurried conversation between a mother and a son. It seemed like an anxious mother in Karachi was relieved to hear that her son was doing fine in Mumbai.

These calls raised the police’s suspicions that foreign organizations were involved in the mayhem that had ensued in Mumbai. Soon, a PCO owner approached the Mumbai Police with more information. Three calls were made from his telephone booth to Karachi, Dubai and Aurangabad.

Investigators continued to track more such suspicious calls from the western suburbs of Borivali and Malad to Afghanistan and Pakistan; some of these calls were made minutes before the first bomb went off. Most of the tapped calls recorded conversations about an accomplished mission.

Another eerie thought struck the investigators when they analysed the locations of the target: had the bomb planters watched the aftermath of the attacks from a safe distance? To make it harder to track the callers, several telephone booths in different locations had been used to throw the investigators off-track.

The handlers, who the police now believed sat across the border, used satellite phones, and most calls were routed through a third country. The only way to get a lead was by tracing all suspicious phone calls until at least thirty days before the incident.

Three months before the train blasts, several hoax calls were received on the Western and Central railway lines, as the planners prepared their final assault. The ATS found out later that the terrorists were carrying out mock drills to confuse the investigators.

During any police investigation, there are hits and misses. Every government agency tried adding new information. Aijaz Hussain, who was arrested by the Delhi Police, was one such ‘miss’. Initially the revelations he had made seemed vital, but the ATS soon reached a dead end following his lead. Also, by the third day there was so much irrelevant information and so many different theories floating around that it seemed as though most of them were a hoax.

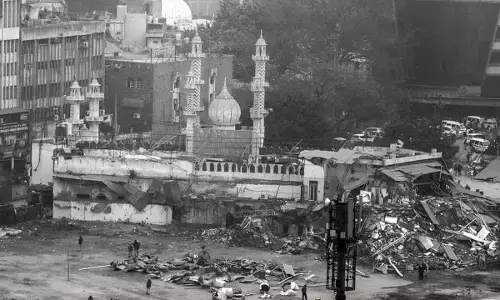

Unlike in the past, Lady Luck was not being kind to the investigating agency this time. In March 1993, the police had managed to crack the serial-blasts case within twenty-four hours because of an explosive-laden Maruti found at Worli and an RDX-laden scooter at Dadar that had led the police to the kingpin of the attacks, Tiger Memon. This time there were no easy clues available.

The ATS geared up for the probe and allotted two senior officers to supervise field investigations. ATS chief K.P. Raghuvanshi’s instructions to his officers were clear—food, family and fun had to take a back seat. ‘Locals are involved in the blasts.

Track them,’ Raghuvanshi told his men. Besides the ATS, the case was also being investigated by the Crime Branch, a unit of the Mumbai Police believed to have a better network of informers; the Special Branch, another unit of the Mumbai Police; the GRP; and intelligence agencies.

By now eighteen teams, of fifty officers each, were trying to hunt down the local bomb planters, many of whom the investigators believed were members of the banned SIMI. The police began combing operations in Muslim-dominated areas like Malwani, Mumbra, Shivaji Nagar and Mira Road.

The operations were intense, with the police picking up 200 men for questioning from Malwani alone. While thirteen people were asked to stay back, the rest were allowed to go home with bruised bodies. Facing harrowing questions from the media and their own bosses, investigators even considered the possibility of India’s most wanted criminal, Dawood Ibrahim, playing a role in the blasts. But that turned out to be another dead end.

In car sheds along the tracks, mangled remains of the train coaches continued to tell the ghastly story of the terror strike. The team of forensic experts studying the evidence suggested that RDX was used in the bombs with pencil or electrical timers.

When clubbed with nitro chloride, RDX is capable of destroying heavy metal. The police also believed that all the timers were set for 6.30 p.m., but a slight error in judgement eventually led to the bombs going off one after another.

RDX had been used twice in the past: once in the 1993 serial blasts and then in the 2003 twin blasts at the Gateway of India and Zaveri Bazaar in Mumbai. RDX was commonly routed through Nepal and Bangladesh, and concealed in boxes of computer hardware, fruits and vegetables.

This RDX found its way to the Marathwada region of Maharashtra, whose districts, including Aurangabad and Jalna, were slowly becoming a hotbed of suspicious activities. The police believed that SIMI members had made Marathwada their home after being driven away from other parts of the state following the ban in 2001. They believed that sleeper cells were active in the region too.

In May 2006, two months before the blasts, the ATS had discovered a large quantity of RDX in Aurangabad and Malegaon. The police seized 43 kilograms of RDX, sixteen AK-47 rifles, 3200 live cartridges and sixteen magazines of AK-47 rifles, and 50 hand grenades but state intelligence officers suspected that at least 1000 kilograms of RDX had been smuggled into India and stored in the Marathwada belt. A large part of this could have been used in the terror strike on 7/11.

At the time of the arms haul, the meaning of what had seemed like a senseless communication, via email, was now suddenly clear. ‘Bachey ki delivery ho gayi hai. Maa khairiyat se hai. (The baby has been delivered and the mother is fine.)’ ‘Shaadi ki tarikh tay ho gayi thi, magar use postpone karna pada. (The wedding date had been finalized, but it had to be postponed.)’

From ‘Six Minutes of Terror’, by Nazia Sayed and Sharmeen Hakim, Publisher: Penguin `209