Live

- Over 7,600 Syrians return from Turkiye in five days after Assad's downfall: minister

- Delhi BJP leaders stay overnight in 1,194 slum clusters

- Keerthy Suresh and Anthony Thattil Tie the Knot in a Christian Ceremony

- AAP, BJP making false promises to slum dwellers for votes: Delhi Congress

- 'Vere Level Office' Review: A Refreshing Take on Corporate Life with Humor and Heart

- Libya's oil company declares force majeure at key refinery following clashes

- Illegal Rohingyas: BJP seeks Assembly session to implement NRC in Delhi

- Philippines orders full evacuation amid possible volcanic re-eruption

- Government Prioritizes Welfare of the Poor, says Dola Sri Bala Veeranjaneyaswamy

- Two Russian oil tankers with 29 on board damaged due to bad weather

Just In

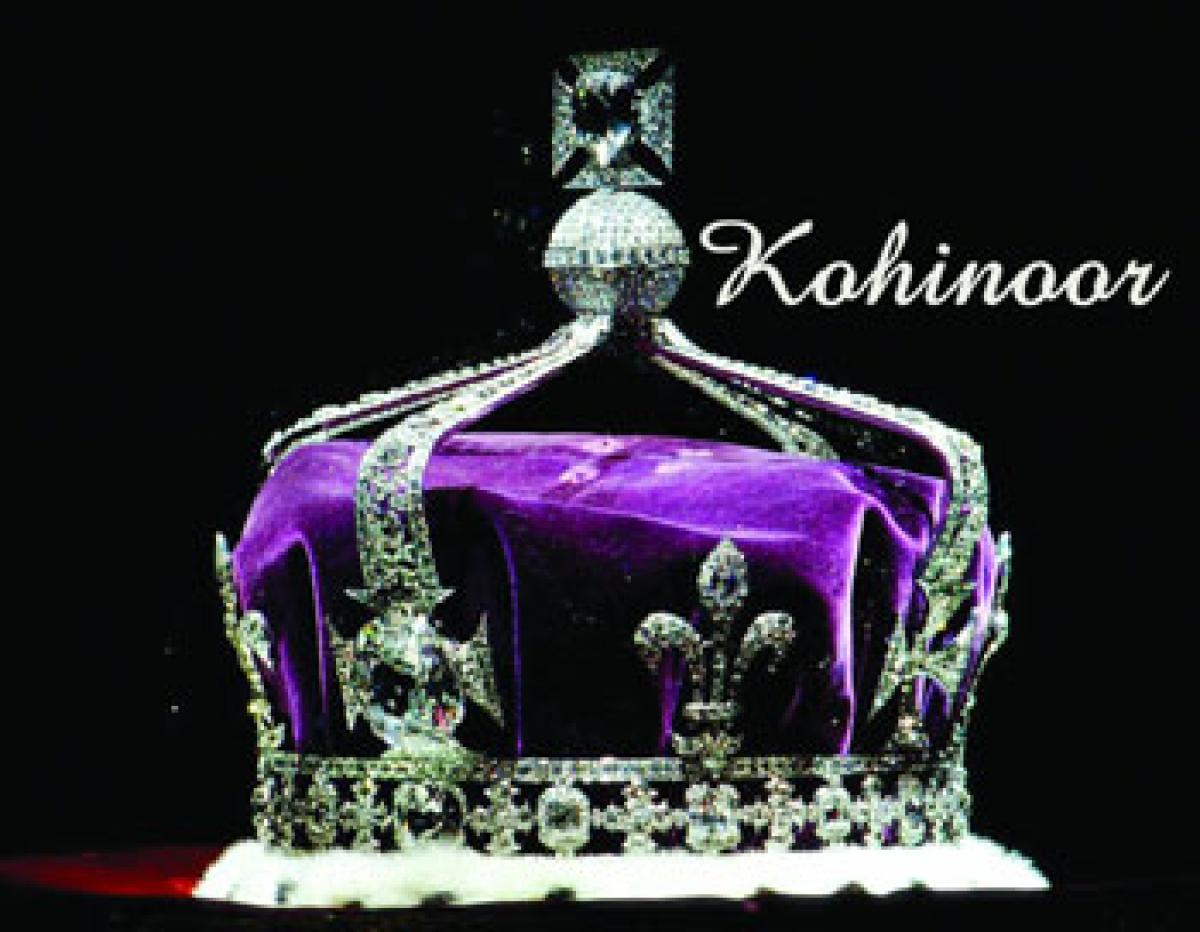

If the place of birth is any claim to ownership, then Koh-i-Noor, the famed diamond now part of the British Crown’s jewellery, should be returned to Andhra Pradesh.

There is no dispute so far as this most controversial gem in the world is concerned – is that “the Mountain of Light or Koh-i-Noor was mined at Vinukonda in the present-day Andhra Pradesh.” But is anyone even talking about it? Individuals, groups and political parties have laid claims, while successive governments have watched with interest, unwilling to take an official stand or act upon it.

There is no dispute so far as this most controversial gem in the world is concerned – is that “the Mountain of Light or Koh-i-Noor was mined at Vinukonda in the present-day Andhra Pradesh.” But is anyone even talking about it? Individuals, groups and political parties have laid claims, while successive governments have watched with interest, unwilling to take an official stand or act upon it.

In terms of history, which is not being disputed, the diamond was originally 793 carats when uncut. It is difficult to imagine it today by gemologists, leave alone laymen. Once the largest known diamond, it is now a 105.6 metric carat diamond, weighing 21.6 grams in its most recent cut state. Now, people from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan are staking claim to it

If the place of birth is any claim to ownership, then Koh-i-Noor, the famed diamond now part of the British Crown’s jewellery, should be returned to Andhra Pradesh.

For, the past records say – and there is no dispute so far as this most controversial gem in the world is concerned – is that “the Mountain of Light or Koh-i-Noor was mined at Vinukonda in the present-day Andhra Pradesh.”

But is anyone even talking about it? Individuals, groups and political parties have laid claims, while successive governments have watched with interest, unwilling to take an official stand or act upon it. The governments realise that it would not help to offend the British and more than anything else, the basic, owner-keeps-it, reality.

On a larger, general scale, we heard a brilliant case for British reparations to India made out by Congress lawmaker and former minister Shashi Tharoor earlier this year. It was hailed far and wide in India and possibly, other former victims of colonialism.

Expectedly, it was lambasted by the British writers who, while they may or may not be proud of their country’s imperialist past, do feel self-righteous about keeping what they got, by grabbing, looting, earning and annexing. Their tone is: “Look the bad boy is at it again!”

Everyone knows the British reparations are not forthcoming, just as the Koh-i-Noor, the other famed diamond, Daria-i-Noor, or for that matter a bulk of the British Crown jewellery, the antiques and other heritage that were acquired through centuries of colonialism, will not.

That has not stopped people from claiming Koh-i-Noor, however. That makes it one of the most recurring themes in the discourse among those who colonised and those who got colonised, anywhere. The latest claim on the diamond is made by a Pakistani lawyer who has filed a petition in the Lahore High Court.

To go back to the place-of-birth aspect and a bit of the past, it is believed to be the mythical Syamantak Mani, the diamond that appears in the Vishnu Purana and the Bhagavata. There is obviously no evidence or historical proof, unless you subscribe to the current “Hindutva-history” ethos.

The Persian name Koh-i-Noor came much later. Part of the mythology, or belief, is also a curse that is placed on the men who will wear the diamond: “He who owns this diamond will own the world, but will also know all its misfortunes. Only God, or a woman, can wear it with impunity.”

After several men lost their lives and kingdoms, Queen Victoria wore it – the reason perhaps that the curse has gained currency. Lady Diana did not live to wear it, nor is Prince Charles getting anywhere near becoming the king.

The future remains uncertain, no matter which king or queen rules England. In the near future, it is likely that if Kate Middleton, the wife of Prince William, who is second in line to the throne, eventually becomes queen consort, she will don the crown holding the diamond on official occasions.

In terms of history, which is not being disputed, the diamond was originally 793 carats when uncut. It is difficult to imagine it today by gemologists, leave alone laymen. Once the largest known diamond, it is now a 105.6 metric carat diamond, weighing 21.6 grammes in its most recent cut state.

It was originally owned by the Kakatiya dynasty (the Telangana angle), that had installed it in a temple of a Hindu goddess as her eye. The diamond changed hands between various feuding factions in the region several times over the next few hundred years. It moved from Raja of Malwa to Alauddin Khilji, the Delhi Sultan, and passed over to the Mughals.

Both Koh-i-Noor and Daria-i-Noor (which means “Sea of light” in Persian) , also one of the largest cut diamonds in the world, weighing an estimated 182 carats, became part of the Iranian Crown Jewels after the Persian victory over the Mughal emperor of India in 1739. Nadir Shah of Persia returned the crown of India and accepted a treasure as a payment which include the Daria-i-Noor, in addition to the Koh-i-noor and the Peacock throne.

The Koh-i-Noor was acquired from the Iranians by Maharaja Ranjit Singh whose capital was Lahore, and his empire was predominantly in the area that is now part of Pakistan. Now, Ranjit Singh was born in the city of Gujranwala. His last surviving granddaughter, Bamba Sutherland, died a Pakistani, lying buried in London at what is called “Gora Kabristan.” Ranjit Singh’s Samadhi is in Lahore with the famed Badshahi Mosque in the background.

This, precisely, is the case being made in the petition filed on December 3 this year by the Pakistani lawyer, Jawaid Iqbal Jafree, making Queen Elizabeth II as a respondent.

It was from Punjab, that was annexed by the East India Company that the British acquired the Koh-i-Noor. Lord Dalhousie, Britain's then colonial governor-general of India arranged for the huge diamond to be presented to Queen Victoria in 1850, during British colonial rule. Travelling with it on the ship, he was supposed to have carried it in a belt with which he never parted.

“Koh-i-Noor was not legitimately acquired. Grabbing and snatching it was a private, illegal act which is justified by no law. Her Majesty the Queen will rise in the highest public interest with facilitating honest disposal and transferring the possession of the Koh-i-Noor diamond which was illegally taken,” says Jafree, who has written 786 letters to Queen Elizabeth II in the last 50 years. The court has not yet admitted it for hearing.

Repudiating Jafree’s claim, Pakistan’s writer Haroon Khalid claims the diamond for Punjab as a whole. Ranjit Singh was the ruler of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, he reminds the current Pakistani rulers who, he says, have repudiated the inclusive approach that its founder Jinnah preached.

“To be a part of this debate Pakistan would need to accept that its history is not just the history of Muslims in the sub-continent, but of all the people that coexisted here before and with the Muslims,” Khalid writes.

Jafree’s claim is the latest in a long line. Mercifully, it has not drawn any significant or angry reactions from India, considering the current phase of strained India-Pakistan ties and the domestic discourse in both countries that has the media, especially the social media, doing all the sabre-rattling.

India also has made regular requests for the jewel's return, saying the diamond is an integral part of the country's history and culture. When India did that in 1976, the then Pakistan premier Z A Bhutto chipped in with a counter-demand. Soon, someone in Afghanistan claimed, saying that Ranjit Singh had ruled there too. And then Bangladesh claimed it, saying it was once part of the British-ruled undivided India.

All this made it most easy for the British to ignore and reject the demand. During a visit to India in 2010, British Prime Minister David Cameron said in an interview on Indian television that the diamond would stay in London. “What tends to happen with these questions is that if you say yes to one, then you would suddenly find the British Museum empty,” he said. Period.

The British divide-and-rule policy worked in the past. Now, Koh-i-Noor remains with the British today for precisely the same reason. But why blame the British?

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com