Sacred vs secular laws

Controversy dodges various temples as their administrators grapple with tradition and custom and the legal issue regarding allowing women entry in a shrines sanctum sanctorum. In defiance of this ritual, around 1,500 women activists gathered at Punes Shani Shingnapur Temple on Republic Day, the latest in many such incidents.

Supreme Court opined in December 2015 on the primacy of Agamas in appointing priests. It held that “denominations” laid out by Agamas such as descendants of particular sages were not based on caste and therefore did not violate Article 17 of the Constitution on abolition of unsociability on which the petitioners based their arguments

Controversy dodges various temples as their administrators grapple with tradition and custom and the legal issue regarding allowing women entry in a shrine’s sanctum sanctorum. In defiance of this ritual, around 1,500 women activists gathered at Pune’s Shani Shingnapur Temple on Republic Day, the latest in many such incidents. This follows three Court verdicts vis-à-vis some Southern temples which have attracted nationwide attention.

Underscoring, signs of a new awakening in sacred-secular relationship in the modern era. Two of these judgments relate to “archakas” (priests) appointment and the compulsory dress code for worshippers in Tamil Nadu’s temples. The third, prohibiting entry to women worshippers in Kerala’s famous Sabarimalai Temple.

Chronologically, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of priests appointment according to “Agama Shastras,” the treatise which prescribes the structure and functioning of Hindu temples, in petitions filed by priests’ association challenging a 2006 Tamil Nadu Government order allowing Hindus with necessary qualification regardless of their caste to become priests in temples in the State. The Court held that deviation from the age-old custom and usage would be an infringement of religious freedom, even as it did not annul the order.

Recall, this debate started in 1972 when the DMK Government amended the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment Act to put an end to the hereditary and common system of appointment of temple priests. This was challenged in the Supreme Court which partially supported the order by abolishing the hereditary system but upheld the authority of Agamas in selection. Plainly, continuance of the prevailing practice and consideration of the “denominations” factor followed in temples.

The issue was laid to rest by another government order, followed by an ordinance and a law declaring people with requisite qualification to be eligible for appointment as priests. Towards that end the State set up Archaka Training Institutes. Pertinently, this order was challenged in the Supreme Court in 2006 which opined in December 2015 again the primacy of Agamas in appointing priests. It held that “denominations” laid out by Agamas such as descendants of particular sages were not based on caste and therefore did not violate Article 17 of the Constitution on abolition of unsociability on which the petitioners based their arguments.

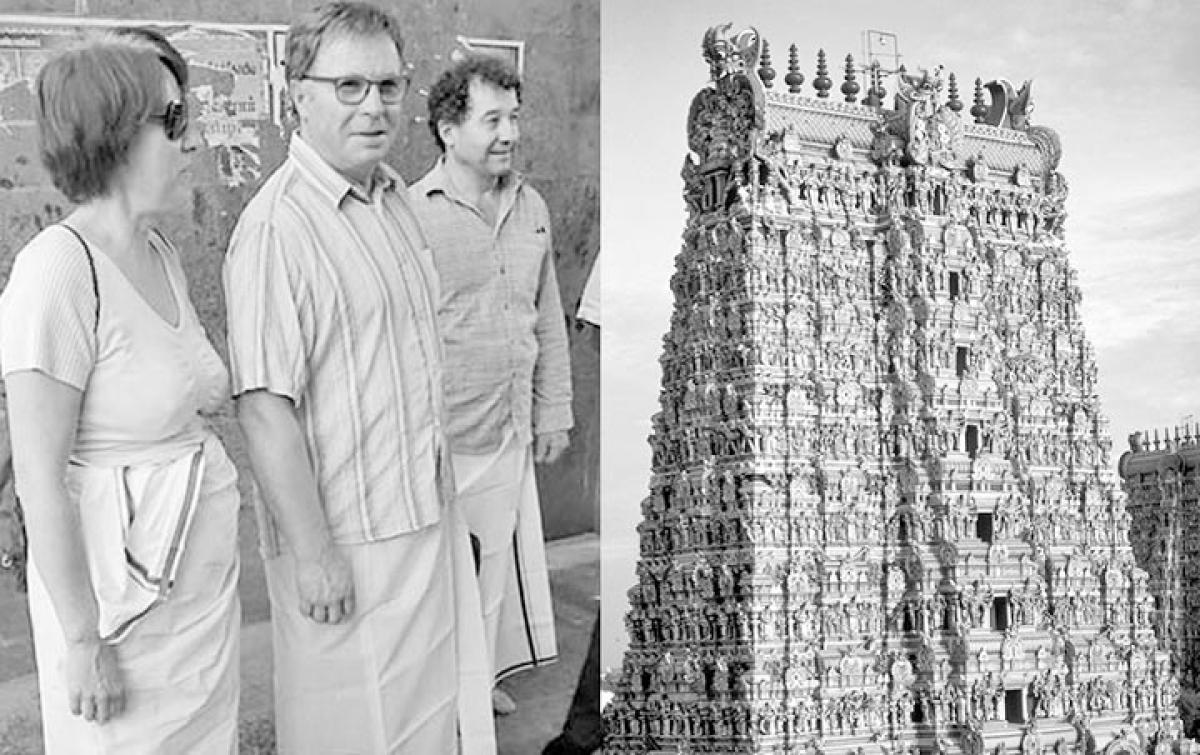

Politically, it is a setback to radical reformist posture adopted by many leaders and Parties in Tamil Nadu over several decades. The second litigation, relating to dress code for worshippers arose out of a directive issued by Tamil Nadu’s Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department following a directive issued by a single Bench of the Madurai branch of the Madras High Court. The code it held was in accordance with the rules pertaining to the attire of devotees and visitors according to the Agamas traditions and customs of the concerned temples and in conformity with the provisions in the Tamil Nadu Temple Entry Authorisation Act, 1947.

Temples started adhering to the dress code from the New Year. Indeed, a dress code is not a novel idea but in practice in many worship places worldwide. But in our country there is a growing tendency to detect a clash between democratic rights and traditional culture in every issue. The Tamil Nadu government then filed a writ appeal against the Madurai Branch’s directive of the ground that the dress code differs from temple to temple according to the local custom and no common code could be prescribed.

This case is now pending before a larger bench. Meanwhile, a stay is in force on implementing the Court order. The third litigation began when a group of lawyers in 2006 sought a directive to allow women entry to Kerala’s Saaremaa Yavapai Temple without age restriction. Presently, girls and women between 10-50 years are barred entry into this temple under the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Rules, 1965 which the Kerala High Court had upheld in 1991.

The Supreme Court has now asked the Kerala government to file a fresh affidavit and stated it would reconsider the case in the light of the fundamental rights and gender equality. Undoubtedly, the judicial reach is expanding due to an increase in controversies knocking on the Court’s doors frequently. Religion-related activities are primarily faith-based and it is difficult to dissociate them from traditions, customs, and usage. But who determines traditions as practiced today is open to question in the matter of worship.

Clearly, many social reforms like abolition of the “Devdasi” system and minimum age for marriage have taken place by eradicating pernicious customs. Simultaneously, traditions and customs also cannot remain static. They have to yield place to reforms to eradicate inequalities and discriminations in worship at public places. To achieve this in a society where religion itself is a way of life, requires a strong will and a capacity to push reforms gently.