Rajini off the beaten track

Even so, a socio-political message on oppression of the Dalits, the country’s most oppressed class, and their rights in a film designed to further the stardom of an established superstar, the way it comes across in the just-released Kabali, is rare and welcome.

Sending message to viewers through a film is as old as the cinema in India that is among the oldest and has emerged as the world’s largest filmmaker. From spreading sentiment against the British rulers to combating narcotics among the young (Udta Punab), that story is nearly a century-old.

Even so, a socio-political message on oppression of the Dalits, the country’s most oppressed class, and their rights in a film designed to further the stardom of an established superstar, the way it comes across in the just-released Kabali, is rare and welcome.

The film is definitely a vehicle to promote the popularity of Rajinikanth, who is acknowledged even by Amitabh Bachchan as the only superstar the country has. Beneath its glamour and action, music and visual effects, however, is an unmistakable political message. While Rajini’s fans are celebrating and even those not touched by “Rajinimania” are watching with awe the hype that accompanied the film’s release, the more discerning are unlikely to miss that message.

Kabali shows that Rajinikanth is evolving. He is ready to break new grounds while trying to hold on to and expand his following among the film viewers. That, perhaps, explains his choice of the film’s director Pa. Ranjith, who earlier made ‘Madras' (2014). Since that film, Kabali has the strongest presence of Dalit talent. Except the principle artistes – Rajinikanth, real name Shivajirao Gaekwad is a Maratha and Radhika Apte is a Brahmin the rest of the crew, director downward, are all drawn from the Dalit pool.

It is hardly surprising that Rajinikanth, a Tamil and a Dalit, is shown reading a book by a prominent Dalit writer in Tamil. Dalit symbols are strewn in numerous details in the film without emphasis. It was widely reported before the film’s release that when Rajinikanth saw the edited version of Kabali for the first time, he said it was “100% the director’s movie and not an inch a Rajini film.” Discerning Tamil cinema watchers spoken to agree.

After years of mega budget, formulaic Rajini films, many will struggle to digest what Ranjith has done. Breaking away from the tailor-made yet typical screenplays often used, Ranjith ventures pretty far off the beaten track. Tamil Nadu's huge Dalit population will ensure the commercial success of this film provisionally slated to have cashed in a conservative Rs 300 crore.

The movie, a gangster action drama, has been released on 10,000 screens around the world, including more than 400 in the United States and several in Britain, China, Malaysia and Japan. More than 20 million people viewed the pre-release trailer on YouTube in just two weeks. But the real madness is taking place in India.

This is the first Indian film for world market at this scale. It has been dubbed not only in Hindi, Telugu, Malayalam and has a Tamil original. It has also been dubbed in Malaysian, Bahasa Indonesia, Japanese, English, Arabic, Mandrin and Portuguese languages. It needs noting that the stage for Kabali was set last year by another mega movie, Bahubali. S S Rajmauli’s film had set high standards in terms of acting, technique, special effects and much else that was indigenous. Its multi-lingual release ensured global success.

It has also raised high expectations for the sequel that is now under production. If Bahubali is a Telugu show going global, Kabali is its worthy Tamil successor. It would be churlish and in any case, too early, to compare the two. The significant thing is that language-wise, both films have smashed the north-south barrier that has given Mumbai-based Bollywood the advantage. Both are not ‘Madrasi’ films. They reach out to Hindi-knowing audiences anywhere.

Tamils are scattered in many countries, but Malaysia has the largest share. That makes this film a worthwhile (and profitable) joint venture, what with its global release and eight major brands endorsing it. Kabali is important because it has broken new grounds outside India. It is billed as Malaysia’s first ‘international’ film venture. Rajini’s character is a Malaysian from a family oppressed by the British and discriminated by the Chinese.

Multi-ethnic Malaysia is home to 2.1 million Indians, a majority of whom settled there during the British colonial era. Also, a bulk of them is Tamils and many are Dalits, from the classes oppressed in India. The caste distinctions have survived in distant Malaysia. Malaysia has 40,000 and neighboring Singapore has 30,000 Telugu-speaking people as well. If Bahubali was embraced there, so must be Kabali. Both films have had Telugu versions released in the United States and the Gulf region.

Made in Tamil and Malay, Kabali has, besides, Indian and Malaysian actors and crew; the Taiwanese actor Winston Chao plays the dapper villain who thirsts for Kabali’s blood. The presence of some marquee Malaysian names like Normal Hakim, Rosyam Nor, Zack Taipan, Tony Kassim and contribution of 1,000 Malaysian artistes and technicians adds to the film’s global lustre. Rosyam Nor is now making a beeline for ‘Kollywood’ in Chennai. Kabali may open the doors for many more.

All this prompted the presence of the top brass of the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC) including ethnic Indian ministers in Prime Miniter Najib Tun Razak’s government to attend the Kuala Lumpur premier. MIC, now in its 70th year, was formed with the Indian National Congress as its inspiration and was formed long before Malaysia (and Singapore) became independent from the British.

Who is Kabali and why? Rajinikanth had the choice of making a sci-fi (like Robot?) or play a real-life don. His daughter Saundarya made him opt for the latter. Thus, disclaimer notwithstanding, Kabali is loosely based on the life a yesteryear gangster, Kabaleeshwaran, who hails from Mylapore in Chennai.

This reminds one of Amitabh Bachchan portraying Mumbai’s “original don” Haji Mastan (Deewar) and Rishi Kapoor playing the fugitive Dawood Ibrahim (D-Day). Tamil Nadu seems to have exported some to Mumbai. Kamal Haasan played Nayakan on the life of varadhararajan Mudaliar (Vardhabhai).

Everyone loves a don. Marlon Brando-starrer Godfather with its sequels is a cult movie. So is Don that Amitabh played in 1973. It has not lost its mass appeal even after Shahrukh’s Don2 partly shot in Malaysia. Shahrukh’s romantic image was enhanced wooing a don’s daughter in Chennai Express. And now there is talk of Don3.

Saying something about the movie, seen first-day-first-show in Downtown Delhi, amidst rapturous screams and whistles of Rajinikanth’s fans would not be out of place. When the don is shot twice, everyone reacts as if he’s dead. Nobody bothers to call for an ambulance. One scene later, he’s alive and on phone, grandly challenging his adversary. Nobody explains how he survived. Superstar is fine, but super-natural?

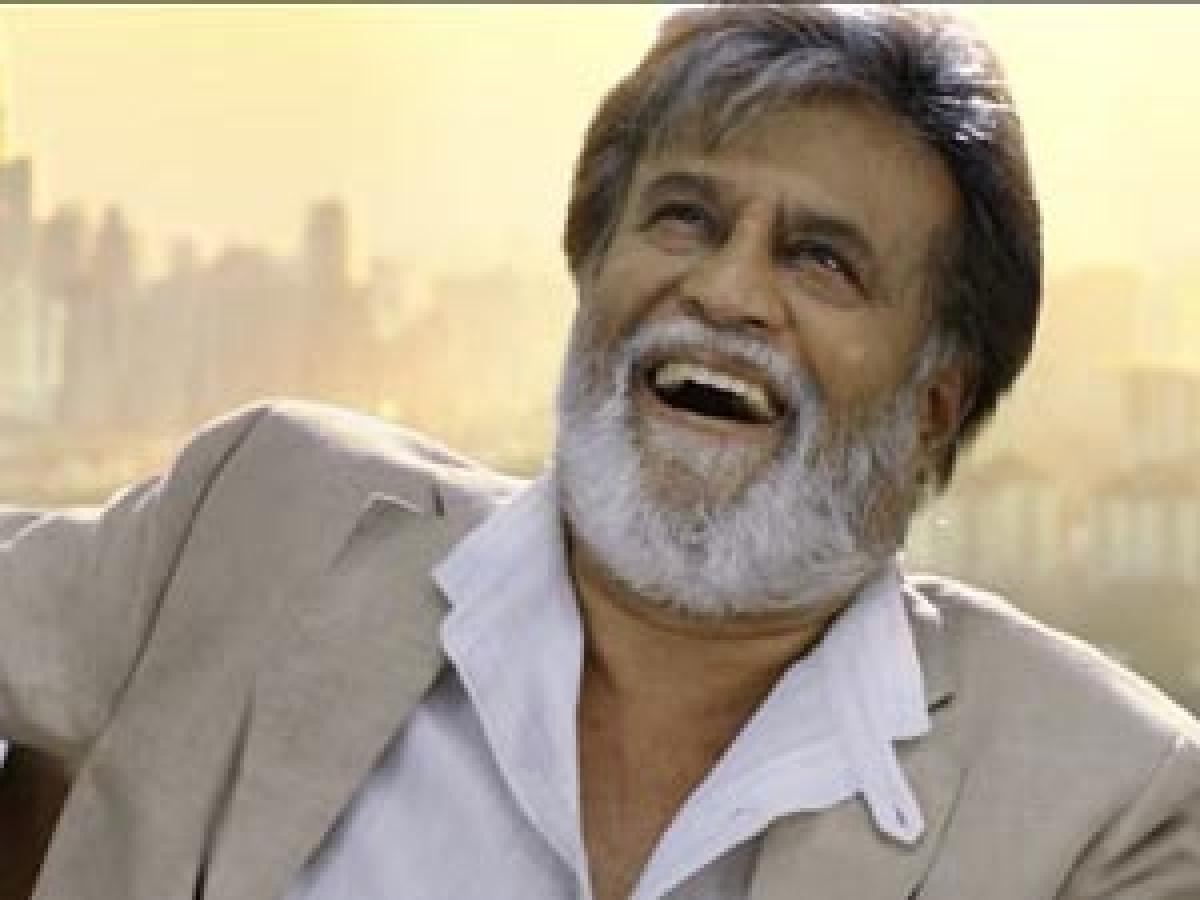

For all its glamour, action, humour and despite good photography quick editing and background music, the film drags. It shows that the superstar is getting slower, less nimble on his feet. Playing his age for a change, he is 65, but a slender, sprightly 65. The older Kabali look is perfect salt and pepper hair, grey beard, white shirt, grey suit, dark glasses. Rajini does look a cold-blooded gangster.

He is the family man the audience loves a gangster with a golden heart. He seeks to reform the youths going bad. He keeps forgiving and that proves his undoing. Where the plot stutters, the subtle mannerisms become the strength of the film deft hand movements, a sarcastic smile on the corner of the lip and close-ups of Rajinikanth where the raw actor in him comes out. And that is why Kabali will be talked about, for Rajinikanth’s emotions.

By Mahendra Ved