Irreversible decline in Chinese population linked to economy

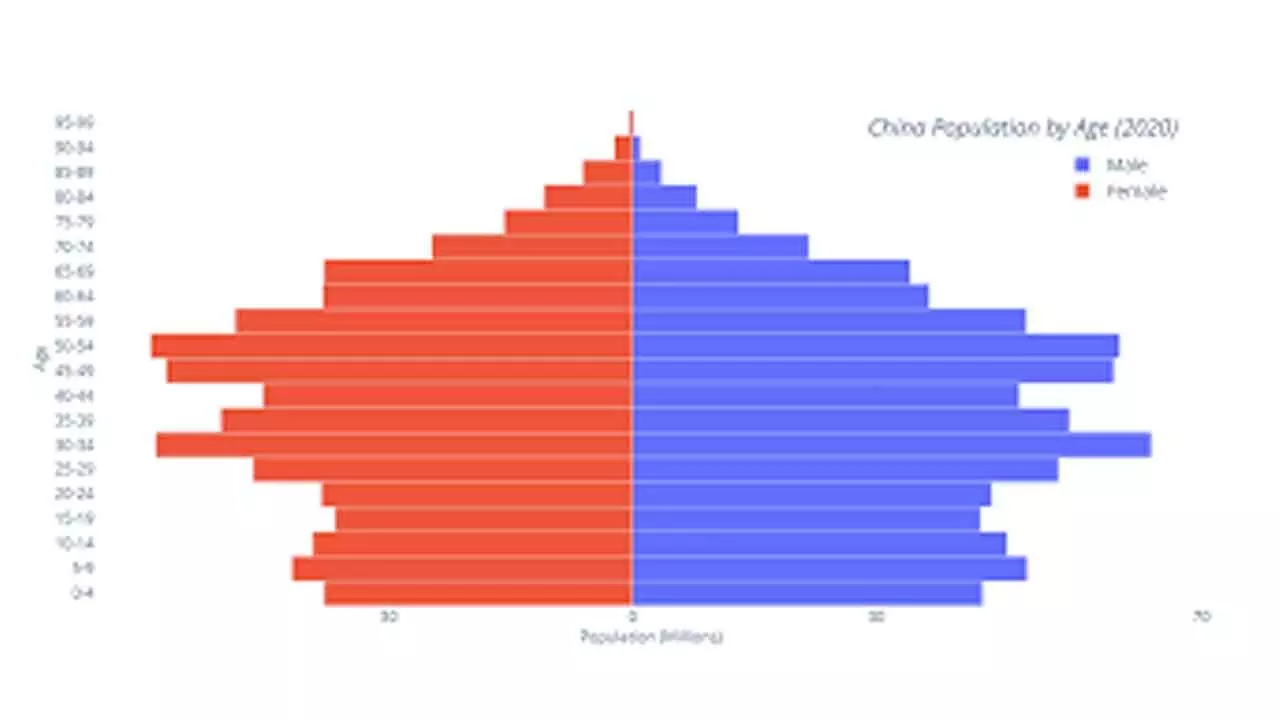

Back in April 2023, the UN acknowledged that India had overtaken China as the most populous country. Incidentally, China’s population reached its peak size of 1.426 billion in 2022, after which it started declining. Projections indicate that the size of the Chinese population could drop below one billion before the end of the century. By contrast, India’s population is expected to continue growing for several decades. The continued low birth rate in recent years in China shows that the damage caused to the population demographic, due to its one-child policy, is reportedly irreversible.

While Beijing has accelerated family-support policies and childcare subsidies, the birth count plummeted to a record low last year -- falling by about 10 million from its 2016 peak, reports the South China Morning Post. China’s population shrank for the fourth consecutive year. As per the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2025, the country saw only 7.92 million births, down 17 per cent from 9.54 million in 2024. “This marked the lowest birth figure since records began in 1949 and broke the previous record low set in 2023,” the report said. Data showed that the country’s total population also fell by 3.39 million in 2025 to 1.4049 billion from 1.4083 billion a year earlier, which marks the steepest annual population decline on record.

Notably, 2025 also saw one of the highest death tolls in five decades at about 11.31 million people. “The pace of the decline is striking, particularly in the absence of major shocks,” Su Yue, principal economist for China at the Economist Intelligence Unit, was quoted as saying. She blamed the declining population rate on a reluctance among young people to get married, combined with rising economic pressures. “The data should serve as a strong signal for policymakers to place greater emphasis on domestic structural reforms.

A more forceful policy response on fertility in the face of a shrinking population is crucial to counter the risk of a smaller consumer base in the future,” she explained. Meanwhile, China has accelerated efforts to revive its declining birth rate by rolling out a series of family-support policies aimed at lowering child-rearing costs and easing the pressures that have deterred couples from having children. In 1971, China and India had nearly identical levels of total fertility, with just under six births per woman over a lifetime. It fell sharply in China to fewer than three births per woman by the end of the 1970s. For India, it took three and a half decades to experience the same fertility reduction.

In 2022, China had one of the world’s lowest fertility rates (1.2 births per woman). India’s current fertility rate (two births per woman) is just below the “replacement” threshold of 2.1, the level required for population stabilisation in the long run in the absence of migration. During the second half of the 20th century, both countries made concerted efforts to curb rapid population growth through policies that targeted fertility levels.

These policies, together with investments in human capital and gender equality, contributed to China’s plummeting fertility rate in the 1970s and the more gradual declines in the 1980s and 1990s. India also enacted policies discouraging large families and took up a national family welfare programme beginning in the 1950s. India’s lower human capital investment and slower economic growth during the 1970s and 1980s contributed to a more gradual fertility decline than in China.