A re-look at globalisation needed

The traditional Hindu method of greeting with a 'Namaste' is often attributed to the need felt for hygiene and cleanliness. The gesture actually signifies gratitude and respect to the person to whom it is intended. Whatever that may be, with the birth and spread of pandemics over the last several years such as SARS, Bird Flu and Swine Flu, and now, the COVID-19, the 'Namaste' is increasingly gaining popularity as the preferred mode of greeting

The advent of the forces of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation in the early nineties of the previous century ushered in the beginning of a new era in the economy of the world. And in India, it represented a second watershed in the country's history as an independent nation, the first having been the successful culmination of the freedom movement, the birth of the republic.

In the 1990s, the United Nations and its organs, primarily the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, decided, with the concurrence of all the member countries, to open up to global competition the markets of individual countries with mandated quality standards and dismantled excessive tariff and duty structures. Economies of nearly every country in the world underwent a process of transformation on account of the emergence of the new forces- and a period of structural adjustment began, in response to the new demands on their socio-economic and political systems.

In a large number of cases, including India, international agencies, such as the World Bank, stepped in to help countries to cope with the pangs of adjustment, with what were known as Structural Adjustment Loans and grants. And thus, began a long and complex series of steps that needed to be taken to ensure that the process of growth and development continued in a competitive environment, but always with a close watch kept on the need for equity and justice.

As has been observed in this column in the past, the new syndrome saw India transit from the Nehruvian - and rather romantic - Mahalanobis phase of growth 'with' justice to the more practical, and contemporary, regime of growth 'and' justice. No longer was implicit faith placed in the process of 'trickle-down' an economic phenomenon, according to which the fruits of growth and development invariably flow to all sections of society, from the richest to the poorest. It was realised that for equity to accompany growth, external and positive interventions would be required.

While growth, driven by large capital inflows took place unhindered and market was allowed to be king, 'safety nets' were also put in place to identify and protect those adversely affected. In that process the cult of integration ceased to be confined merely to economies, and spread to other sectors, such as Science and Technology, Education, Health, Trade, Commerce and Industry.

The Central and state governments began a process of gradual withdrawal from certain sectors. Privatisation of public transport had already occurred to a large extent. Now, following an aggressive exit policy, the Central government began to concede to the private sector considerable investment and activity space in sectors such as civil aviation, telecommunication etc. Even the railways, which initially remained solely within the realm of the public sector, has now started selectively parceling out, or outsourcing, parts of its activities to private players.

It was mostly in the areas of social infrastructure, such as health and education, that the impact of growth on equity was seen to have a sharp impact. The quality of delivery of services no doubt improved considerably but, simultaneously, there was a steep rise in costs, with the increasing private investment and growth triggered inflation.

Remedial measures were promptly appropriately instituted say, initiating programmes such as 'Arogyasri' in the erstwhile Andhra Pradesh state and corrective supportive measures like reservations and scholarships for the those belonging to the Scheduled Castes, the Scheduled Tribes, certain backward castes, as well as some economically backward classes, in the field of higher education were introduced. In other words, appropriate "safety net" measures were being put in place from time to time.

It was largely in the power sector, however, that the policies of various states came into sharp conflict with the recommendations of the international lending institutions such as the World Bank. In the name of favouring agriculture and driven largely by political considerations, the public sector undertakings in the power sector were ordered to distribute power at heavily subsidised and, very often, zero cost.

Naturally this impacted adversely on the profitability of the power distribution companies and the tariffs payable by industrial, commercial and domestic consumers had to be raised steeply in order to cross- subsidise the operations of the undertakings.

Borders dividing countries soon became mere geo- political entities. Countries that were earlier separated, by barriers such as language and culture, found a new way of discovering oneness, between and amongst them, in the amalgamation provided by universal media of communication, such as the internet.

With the globalisation of the economies, the world has become one with growing international relations in trade and commerce as well as tourism and social contacts. Developments such as these have also impacted all other aspects of human relations. One such is the gesture used for greeting others. For centuries, especially in the western world, the shaking of hands has been the most common way of exchanging greetings, whether by way of love, affection, friendship or, on occasion, making up after a period of rivalry or bitterness.

But it is gradually being realised that shaking of hands is much more than merely a gesture of goodwill. In addition to the affection that is communicated by the contact and the gesture of friendship that the act represents, there is always the possible danger that bacteria or viruses may also move from one person to the other.

The traditional Hindu method of greeting with a 'Namaste' is often attributed to the need felt for hygiene and cleanliness. The gesture actually signifies gratitude and respect to the person to whom it is intended. Whatever that may be, with the birth and spread of pandemics over the last several years such as SARS, Bird Flu and Swine Flu, and now, the COVID-19, the 'Namaste' is increasingly gaining popularity as the preferred mode of greeting.

With the increase in speed of travel, whether by air, sea, or land, and the consequent explosive growth in the field of connectivity of various parts of the world, goods, services, and even persons, are taking less and less time to reach faraway places. In a manner of speaking, distance no longer mattered and distance stood annihilated. Quite apart from the many positive advantages of such a technological achievement, there is the danger also of infections spreading quickly and widely, a danger that can hardly be ignored anymore, as is evidenced by the current phase of COVID-19.

It is thus being realised that dismantling of the barriers of entry and exit, and integrating with other countries, results not merely in the globalisation of markets but also of certain vulnerability and exposure.

Thus, while nations of the world are generally enthusiastic about the advantages the forces of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation brought with them, they are now beginning seriously to wonder whether 'localisation' might not be a highly necessary, if not essential, approach to international relations, especially in the field of public health.

And here lies the rub. In their anxiety to insulate themselves from the possible risks free travel brings, countries should be careful not to lose the advantages that globalisation brought in in other forms earlier.

All countries need also to recognise the opportunity that the current situation presents, to consolidate and improve their health and medical infrastructure. The recently conducted SAARC video conference would have been much more reassuring and productive if the announcement following the conference had also contained a resolution to strengthen the equipment and personnel manning the laboratories entrusted with the task of testing the presence or otherwise of the Corona virus and could have taken the lead and showed the way to the other countries. Committing adequate resources for that purpose would also have gone a long way in substantially enhancing public confidence in the ability of the SAARC countries to handle the emerging situation effectively. International cooperation should go that little further than mere expression of goodwill and solidarity and tackle specific issues with a sense of purpose and determination.

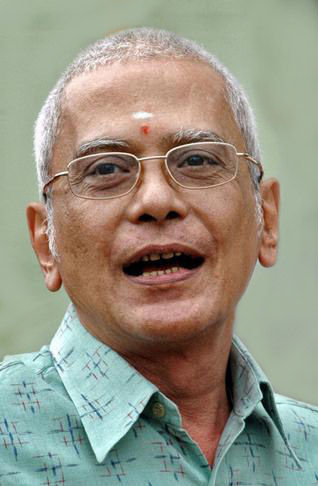

(The writer is former

Chief Secretary, Government of Andhra Pradesh)