The oppressive transformation

For a brief period in the early 1980s, most variants of popular Hindi cinema across the big, the small, as well as the middle variety, happily shared the same space and, in fact, co-existed within the minds of the audiences as well. What separated this period from any other in the then six decades that cinema in India had existed was that for a brief period almost three generations of filmmakers w

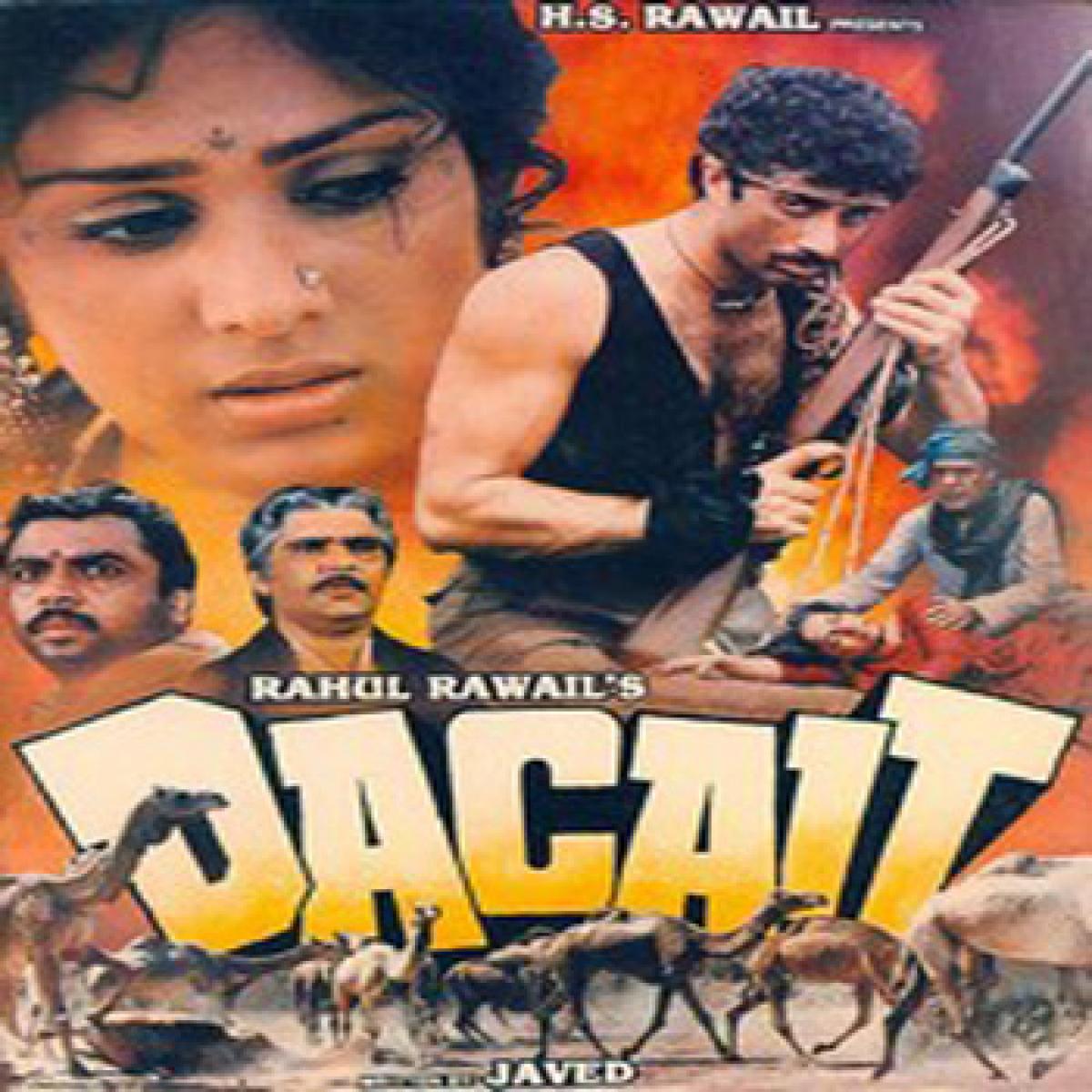

Rahul Rawail’s ‘Dacait’ (1987) was the biggest blow to popular Hindi cinema and the manner in which the high-profile film tanked somewhere, pushed mainstream cinema back by decades

For a brief period in the early 1980s, most variants of popular Hindi cinema across the big, the small, as well as the middle variety, happily shared the same space and, in fact, co-existed within the minds of the audiences as well. What separated this period from any other in the then six decades that cinema in India had existed was that for a brief period almost three generations of filmmakers were making films at the same time.

With popular filmmakers such as Raj Kapoor, BR Chopra, Chetan and Vijay Anand, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Raj Khosla to Yash Chopra, Manmohan Desai, Prakash Mehra to Subhash Ghai, Mahesh Bhatt, Shekhar Kapur and Rahul Rawail making the films they were best known for, and parallel cinema’s Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani and Saeed Akhtar all getting to make their kind of films, the decade showed immense potential to change many definitions.

Additionally, this was also a time when new leading men and women were emerging from the shadows of the past. While an Amitabh Bachchan was still going strong, winds of change were sweeping the landscape in the form of Kumar Gaurav and Kamal Haasan followed by Naseeruddin Shah, Sunny Deol, and Anil Kapoor along with an up and coming Sridevi and Deepti Naval, who were fast replacing Hema Malini and Shabana Azmi or Smita Patil as options.

Although it’s not entirely possible to pinpoint when Hindi cinema made the promise of a possible change, the moment when it conceivably broke the pact is. While parallel and middle cinema had their own struggles by the mid-1980s. One of the poster boys of the so-called new Hindi cinema, Rahul Rawail was the filmmaker who launched the careers of Kumar Gaurav with ‘Love Story’ (1981), a spat with the producer, Rajendra Kumar, saw Rawail not get the final credit for directing film, and Sunny Deol with ‘Betaab’ (1983), Rawail was one of the most sought after filmmakers in the 1980s.

Along with Subhash Ghai and Shekhar Kapur, Rawail formed a neat troika of sorts that was largely responsible for the new blood in popular Hindi cinema. ‘Dacait’ came at a time when Bachchan was busy in the throes of politics and with the industry seeking a new numero uno amongst the leading men the spotlight had fallen on Jackie Shroff, Anil Kapoor, and Sunny Deol.

In this lot the main contention seemed to be between Kapoor, who had graduated from being a strong supporting act in ‘Mashaal’ (1984) to a full-fledged hero with ‘Meri Jung’ (1986) and Deol, who with ‘Arjun’ (1985), which was also directed by Rawail, had displayed enough prowess to take on the mantle of the new “Angry Young Man”.

Interestingly enough the breakthrough films of both Kapoor and Deol were written by Javed Akhtar and perhaps, therefore, the expectations from ‘Dacait’ were sky-high as besides being written by him, it featured Deol in the lead and had Rahul Rawail calling the shots.

The film followed the trials of the city-educated Arjun Yadav (Deol) who returns to his village to discover that the local zamindar Thakur Bhanwar Singh’s (Raza Murad) land grabbing antics have forced his friend Makhan Mallah (Raj Nanvag) to become a dacoit. Arjun’s elder brother Amrit (Suresh Oberoi) gets into a tussle with Bhanwar Singh’s son, Badri (Dan Dhanoa), which leads to a blood feud between the two families.

Arjun tries to follow the path of law by trying to register a complaint against the Thakurs but the no-good local cop Vishnu Pande (a stellar Paresh Rawal) ensures that nothing comes off it. On the day of the marriage of Arjun and Amrit’s sister, Shanta (Urmila Matondkar), Bhanwar Singh avenges his son’s honour. Amrit is killed and hung from a tree, Shanta is raped and forced to commit suicide and their mother (Rakhee) with a shaved head is made to dance in front of everyone.

Bhanwar Singh leaves Arjun to die but fate decides otherwise. Arjun survives the ordeal and becomes a dacoit hiding in the ravines and plotting his revenge. In many ways ‘Dacait’ is the ideal Hindi film that came to define the 1980s – it tried to mix art-house and popular and attempted something that was same, same but different.

It was a throwback to the yesteryears in terms of characters, theme as well as the narrative but Rawail tried to adorn it with a different treatment. Dacoit films have been a near rite of passage for many stars – Dilip Kumar (‘Ganga Jamuna’ (1961), Sunil Dutt (‘Mujhe Jeene Do’ (1963), Dharmendra and Vinod Khanna (‘Mera Gaon Mera Desh’ (1971), Amitabh Bachchan (‘Ganga Ki Saugandh’ (1978), Mithun Chakraborty (‘Daata’ (1989) and later Sanjay Dutt (‘Jai Vikranta’ (1995) – and while most films have high drama (‘Heera’ (1973), ‘Rajput’ (1982) and extremely stylized (‘Sholay’ (1975) some like ‘Ghulami’ (1985) and ‘Batwara’ (1989) still managed to explore the intricacies of the caste system that led to young men taking up arms.

‘Dacait’ follows the tradition of ‘Mujhe Jeene Do’ and ‘Ganga Jamuna’ where it probes the circumstances that prompt the making of a brigand and tried to balance the art and commerce. According to an interview given by the film’s cinematographer Ranjan Kothari in the book ‘40 Retakes’, ‘Dacait’ seemed to lose track towards the second half and especially due to the manner in which Javed Akhtar and Rahul Rawail approached the climax of the film.

Apparently Rawail wanted the end to feature Arjun strangling Bhanwar Singh with a sash that he tied around his head but Akhtar thought it was too ‘unheroic.’ Even though two endings were shot, the one retained was Akhtar’s version that featured Arjun gunning down Bhanwar Singh and Shafi Inamdar, an honest super cop who sympathises with Arjun, shooting him.

In a time when ‘Bandit Queen’ (1994) and ‘Paan Singh Tomar’ (2010) hadn’t happened and mainstream cinema was largely experienced to be entertained, ‘Dacait’ might have felt a tad too much of a downer. The fiasco of the film prompted commercial Hindi cinema to revert to somewhat safer bets and an example of this can be clearly seen in the way one of the then most promising young filmmakers, Subhash Ghai went from ‘Meri Jung’ to ‘Karma’ (1986) to ‘Ram Lakhan’ (1989).

Today, watching ‘Dacait’ seems like watching two different films split by an interval where the first-half that looked weaker on paper to the filmmakers seems more organic and the second half, which felt stronger during the narration, appears perfunctory and listless. But irrespective of what hindsight might proffer, ‘Dacait’ is a worth more than a second look.