Better days for Pak minorities?

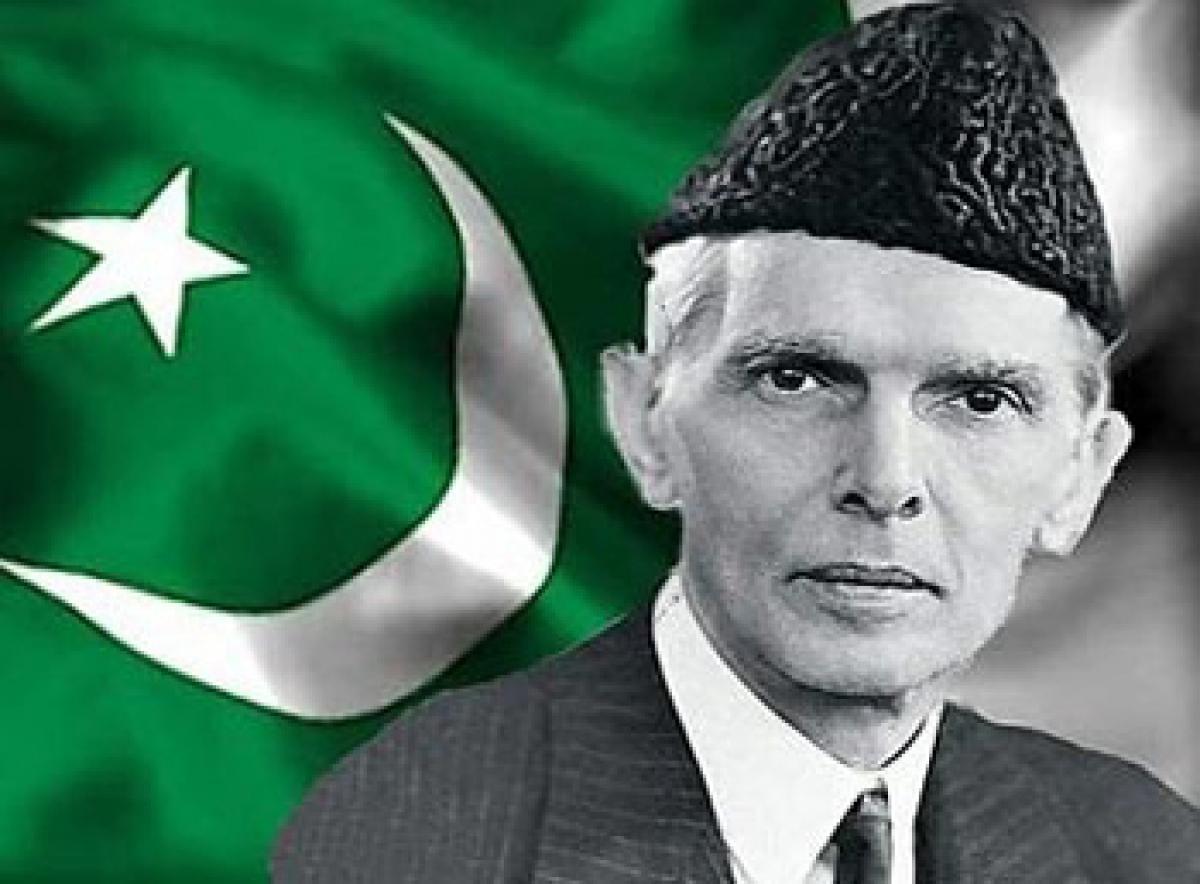

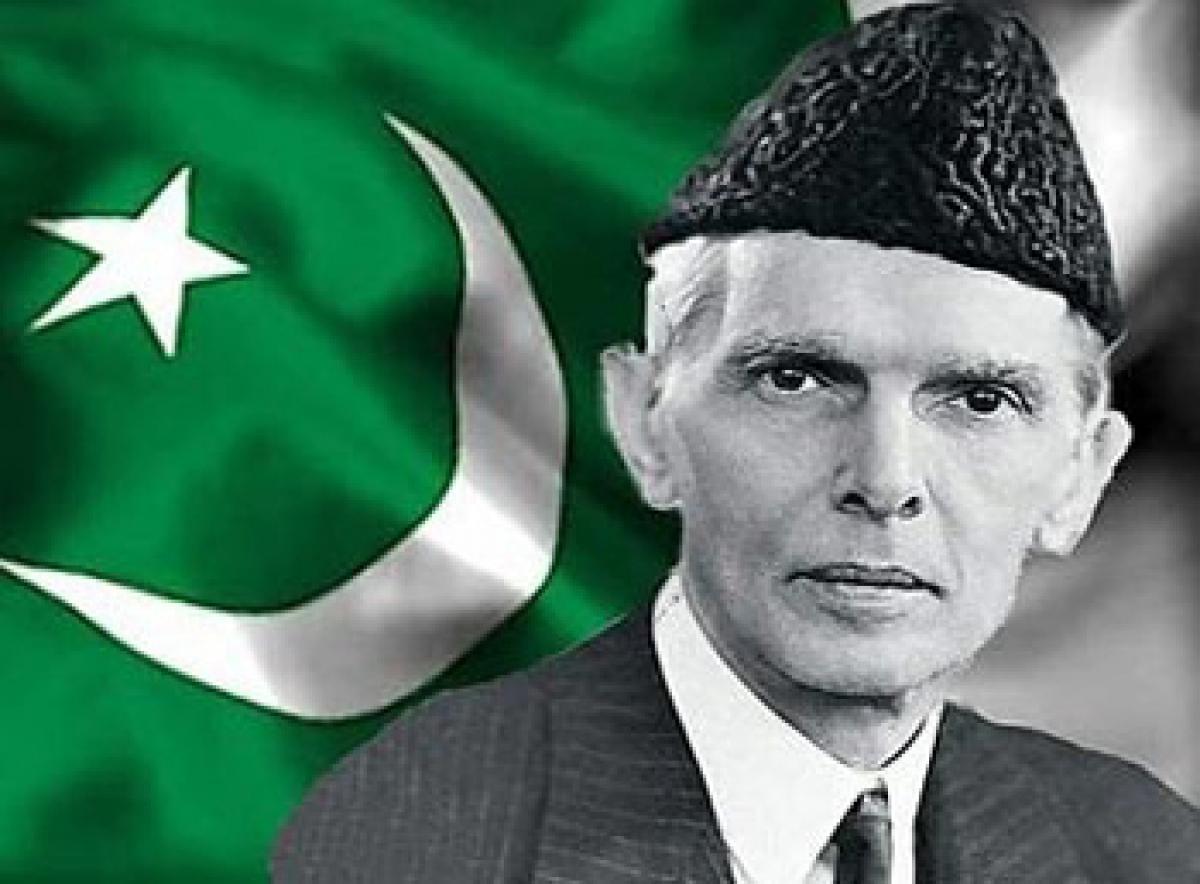

Better days for Pak minorities. That Pakistan is unkind to its religious minorities is widely known. But that its National Assembly has passed a resolution seeking a better deal for them, citing the wishes and a speech of its founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, does make news.

National Assembly has passed a resolution seeking a better deal for them, citing the wishes and a speech of its founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah. He had said: “You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the state… You will find in course of time that Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state. However, Pak paid no heed to the voice of its Quaid-i-Azam Urdu for 68 years. That an attempt is being made to correct itself and assure the much-needed rights to the minorities is significant.

National Assembly has passed a resolution seeking a better deal for them, citing the wishes and a speech of its founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah. He had said: “You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the state… You will find in course of time that Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state. However, Pak paid no heed to the voice of its Quaid-i-Azam Urdu for 68 years. That an attempt is being made to correct itself and assure the much-needed rights to the minorities is significant.

Plight of minorities in Pak

There is no system in place in Pakistan for registration of marriages of Hindus, Sikhs and Baha’is. This means that they can’t legally prove their marriages at home and abroad, and wives can’t claim property of their dead husbands. In the absence of the law, the Hindus, particularly women, suffer for want of a marriage certificate. Unable to prove their marital status, they are also subjected to kidnapping and forced conversion for marriage

That Pakistan is unkind to its religious minorities is widely known. But that its National Assembly has passed a resolution seeking a better deal for them, citing the wishes and a speech of its founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, does make news. To many in India, that Pakistan observes “Minorities Day” may also be news. It needs recording here since last week’s development went unreported.

.jpg)

Let it be stated at the outset that the resolution and the debate that preceded it are likely to be dismissed as tokenism. They may well be so. But they must be noted for a simple reason: India’s own record of treating its minorities is questionable. It is relatively better, but there are no brownie points to be scored by making a comparison.

It is true that there is no system in place in Pakistan for registration of marriages of Hindus, Sikhs and Baha’is. This means that they can’t legally prove their marriages at home and abroad, and wives can’t claim property of their dead husbands. In the absence of the law, the Hindus, particularly women, suffer for want of a marriage certificate.

Unable to prove their marital status, they are also subjected to kidnapping and forced conversion for marriage. Absence of law also complicates other marriage-related issues like inheritance and adoption. Because of the absence of law, the minorities are also short-changed in the issuance of the government’s Computerised National Identity Cards. A more pluralistic India does score when seen in this light.

Precisely for this, it should take note of developments across the border. The Pakistan National Assembly chose for debate and adopting of the resolution August 11, the day in 1947 when Jinnah, with three days to go to Pakistan’s birth, had made a speech that he regarded as roadmap for Pakistan’s future. He had said: “You may belong to any religion or caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

He had also said: “You will find in course of time that Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state.” The resolution was moved by Ports and Shipping Minister Kamran Michael, a Christian. Many Members participated before it was adopted.

It was agreed that efforts would be made to make this passage a part of the country’s ethos and governance – 68 years after the speech was made. Some members wanted it to be made an integral part of the Constitution. Such efforts were made by M P Bangara, a Parsi lawmaker, in 2007, but did not succeed. Reporting the Assembly proceedings, the Dawn newspaper noted that unlike some other past occasions, the resolution was not opposed by the Islamist parties.

“There was no opposition to the resolution in the depleted house, though hardline religious scholars, like those in the government-allied Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam (JUI-F) and the opposition Jamaat-i-Islam, have in the past disputed a secular interpretation of the Quaid’s vision, which they say was actually of an Islamic state.” The lack of opposition by members of religious parties in the Assembly to what was clearly promotion of a secular point of view was unthinkable even a year ago.

Now, the militants’ mayhem has changed the mood. This part of Jinnah’s speech has for long been the sin qua non of Pakistan’s minorities, the liberals, the socialists and those who look to Jinnah as the modern, moderating influence on a nation created on partition of the Subcontinent on religious basis. It has been suppressed by many past regimes, subjected to misinterpretation by the conservatives and the clergy who have viewed from the prism of Islam and Islamic ethos alone.

That Pakistan of Jinnah’s vision lost its way. The National Assembly resolution is a strong reminder of that. Pakistan has had no population count for long. The US State Department's International Religious Freedom Report 2002 estimates Christians at 2.09 million; Ahmadis at 286,000, Hindus at 1.03 million; Parsis, Buddhists, and Sikhs at 20,000 each; and Baha'is at 50,000-100,000.

In an editorial hailing the Assembly resolution, Dawn observed: “At long last, and with one resounding voice, the representatives of the Pakistani people have spoken for the minorities of this country. In so doing, they may have taken a historic step towards a course correction for Pakistan’s future.” It noted that elsewhere, the resolution may read like an assertion of the obvious. But “in Pakistan it is difficult to overplay its significance, both from the point of view of content and timing.”

After independence, “contrary to Mr Jinnah’s words, the state lost little time in recasting faith — specifically the faith of the majority — as its raison d’être, and later, as the cornerstone of its foreign policy. A triumphalist narrative, especially from the ’80s onwards, was deliberately nurtured through means both subtle and overt, and the minds of entire generations poisoned for short-sighted objectives.”

The fallout within Pakistan, it lamented, “has been devastating, as witnessed in the lynching of blasphemy suspects, sectarian killings, the sacking of localities with minority populations, and the bombing of religious processions and places of worship, etc. Although religious extremism has disproportionately affected minority communities, it has over time morphed into the bedrock of a vast terrorist network that the state is now battling to destroy.”

The newspaper opined that for enduring change in the Pakistani society, “school curricula should be purged of divisive, prejudiced material, the country’s pluralistic heritage celebrated, and the blasphemy law revisited.” Some Pakistanis take the cue from India. Burjor Rustomji, a Parsi living in Pakistan writes: “Our good neighbor India has had three Muslim Presidents, besides many people of the minority communities in top responsible positions like Army Chief and Chief Justices.

We in Pakistan have a very myopic view of our nation, of our neighborhood and the world….. India adopted Mr. Jinnah's speech both practically and in spirit 68 years back, without a word. We have only just realised our mistakes, after losing thousands and thousands of innocent lives.”

This narrative cannot be complete without noting a video just out, “Saluting minorities: Gao Suno Badlo” that signs off with ‘Aao Sab Ko Karain Salam’. The simple lyric by Salman Haider needs no translation. “Kaheen khel ke maidaanon me, Kaheen adl k aiwanon me, Koi mehnat kash ka saathi, Koi sarhad pe de pehra, Koi dard ka daru thehra, Koi kaanon me ras gholay, Koi lafz ki girhen kholay.”