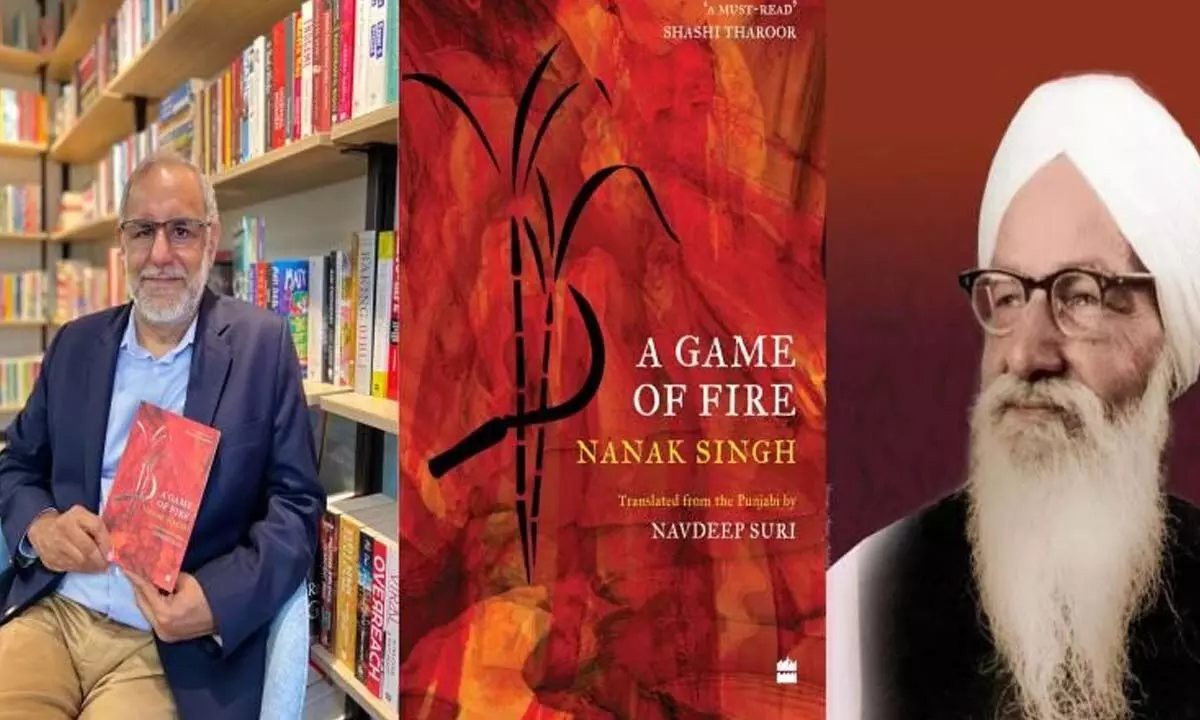

Ex-diplomat discovers Amritsar’s dark side while translating his grandfather’s book

When India was celebrating its 75th year of independence, author and former diplomat Navdeep Suri thought it was important that we realise the price we paid for it.

When India was celebrating its 75th year of independence, author and former diplomat Navdeep Suri thought it was important that we realise the price we paid for it. He says in many ways ‘A Game of Fire’ (HarperCollins India), which his grandfather Nanak Singh wrote in Punjabi decades ago, holds more significance today.

‘A Game of Fire’ is a sequel to ‘Hymns in Blood’ by the same author, also translated into English by Suri, who believed that the stories of the pain of Partition should reach a wider audience conversant with the English language. And in the process of translating his grandfather’s books, he discovered more about the latter’s personality.

“Translating these two novels was a discovery and a journey at two different levels. The first was that I discovered my grandfather, you know, because he passed on when I was just 12. While translating, I got acquainted with his robust opposition to communalism, his staunch, almost iron cast, and uncompromising position for a secular India,” Suri said, adding that while Nanak Singh was a devout Sikh, for him, humanity took precedence over religion.

The Partition stories that a generation grew up with were always about the atrocities that were committed by Muslims on the Hindus and Sikhs, accounts conditioned by the refugee narrative, but his grandfather through the book acquaints us with what the other religious groups did to the Muslims at a time when a collective madness descended upon the sub-continent.

And that’s not a story that many of us are comfortable telling or listening to, Suri added.

When he was researching his subject, the translator came across the startling fact that the last Census before Independence, which was conducted in 1941, showed that 46 per cent of Amritsar’s population was Muslim, but, as Suri pointed out, “I grew up in a city where there were virtually none”.

Stressing that the exodus of Muslims left a big gap in the culture of Punjab, the author told IANS that the exodus of a large number of creative people -- writers, artists and singers, who had been forced to go to Pakistan -- affected the soul of the state. “Manto wrote passionately about his experiences. Of course, the same holds true for Lahore from where many Hindus migrated to India,” Suri pointed out.

For someone who has extensively translated works from Punjabi into English, Suri knows too well that it is never easy for a translator to be ‘invisible’. “Being a translator, you are bridging not just the language, but also the time and space set in a certain geographical context. And in a certain time, context. One hopes to make it accessible to an audience that could be anywhere,” Suri said.

He continued by pointing out: “I personally feel it is very hard to stay invisible. Almost every translator will inject a piece of her or him into the translation. That is why today some people are saying, let’s call it transcreational. Yes. Because translation is as much of an art form as writing. One does leave her/his footprint as a translator. You’ll see that each one is different.”

Talking about his process, Suri said that as a translator he likes to ensure that the substance must retain fidelity to the original.

He noted: “But you have to ensure that it is also readable. You cannot do it line-by-line. You want to try and pick up a chunk and convey the context. It is important to make sure that the flavours of the original are retained to the greatest extent. You don’t want to over-explain. After all, one has to trust the reader’s intelligence as well.”

In the last 15 years, we have seen a revolution in translations from Indian languages into English, and the books getting major awards, Suri pointed out, emphasising that we have incredible literature in India.

“And everyone must be able to access it. What translators can do is really create bridges between different parts of the country,” Suri noted.

Currently taking a break, Suri plans to write something about the UAE, where he was posted as ambassador before his retirement from the IFS, and the momentous transformation in relations that we have seen between India and the emirate. “Also, I am blessed that my grandfather left us this enormous corpus of 59 books, including 38 novels. So, there’s plenty to choose from. The one that I have in mind, frankly, as the next one, is a masterpiece of his called ‘Ik Meyan Do Talwaran’, for which he won the Sahitya Academy Award in 1962,” Suri said. And to pique our interest, he added: “That is a book about the Ghadar movement. And Nanak Singh did extensive research and even spoke with many of the ‘Gadhari Babas’ who were still around in the late 1950s and early 1960s.”