Snake In the Mind’s Lake

The hitherto unchallenged snake is enraged. It raises its hoods and coils around Krishna and stings him in several parts of the body. All the dwellers of the cowherd habitation stand on the bank, highly petrified and worried about Krishna’s safety. The boy is unaffected, but he expands his body (bhakti grows gradually once it enters the mind) and that stifles the snake. Krishna wheels around the snake fast, holding its tail, bends its hump and jumps on to the hoods. It is such a great dance that even the divine musicians enter the scene and play their instruments

Indian thought analyses the mind in four levels. The first is merely to cognize a thing, and this level is called manas. The next level is to know and judge what it is. This level is called buddhi, the discriminating ability. The third is the notion of ‘I’, or ego, which is called ahamkara. The fourth level is the ability to collect from the pool of data; this is called chittam. All four are collectively called the antah-karana, the inner organ.

It is interesting to note that the manas and chittam are words of neuter gender. Buddhi is feminine in gender, and ahamkara is masculine. The ego sometimes controls buddhi, and sometimes buddhi controls the ego, as it happens in the case of a husband and wife.

The ego can sometimes be highly poisonous, hurting all people and spoiling the entire mind lake, like the serpent Kaliya in the story from The Bhagavatam. It can be a multi-headed snake, Kaliya, which means it has many factors that make a person egotistic – wealth, power, knowledge, beauty, achievements, rivals to be crushed, and so on. Anyone going near gets the poisonous fumes, gets hurt and runs away, as in the case of Kaliya, who entered a huge lake abutting the river Yamuna.

Now, the symbolism of the story is getting clear. When mentioning a lake such as manas sarovar, it usually refers to the mind. In the present story, we find that all the people who drink its water fall dead. Krishna is still a cowherd boy, taking his cows into the forest along with fellow cowherd boys. He sees his dead friends, and he becomes furious. He jumps into the lake and creates a huge flutter.

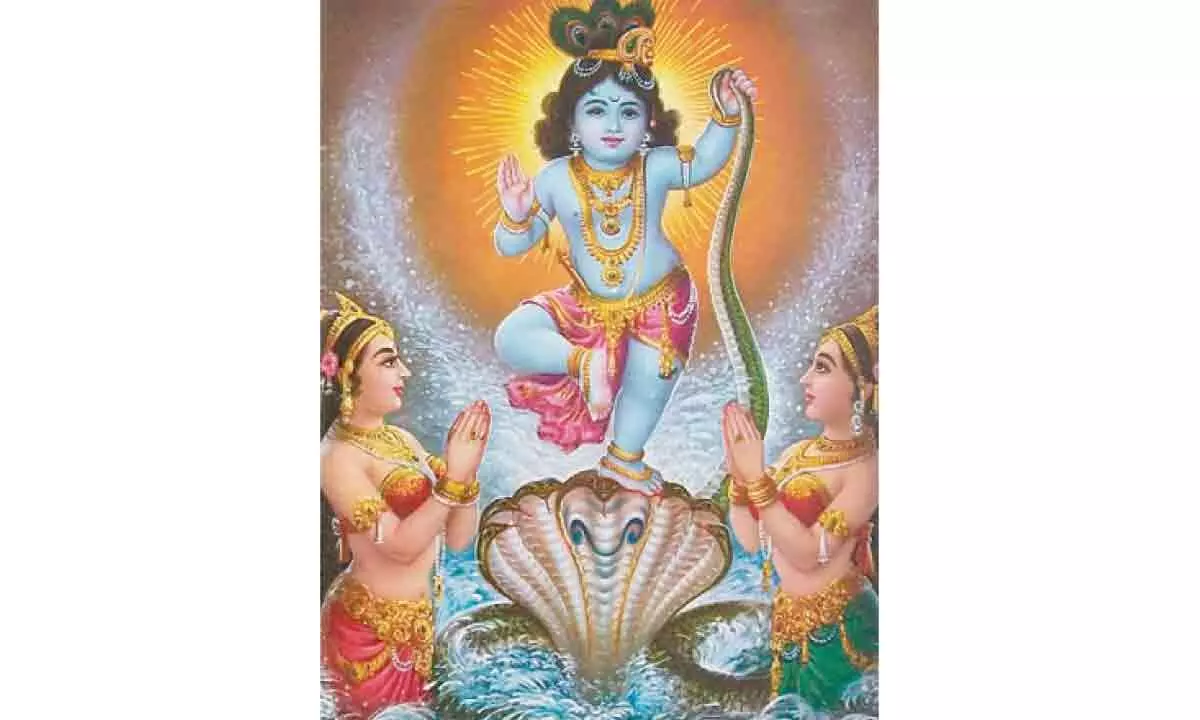

The hitherto unchallenged snake is enraged. It raises its hoods and coils around Krishna and stings him in several parts of the body. All the dwellers of the cowherd habitation stand on the bank, highly petrified and worried about Krishna’s safety. The boy is unaffected, but he expands his body (bhakti grows gradually once it enters the mind) and that stifles the snake. Krishna wheels around the snake fast, holding its tail, bends its hump and jumps on to the hoods. It is such a great dance that even the divine musicians enter the scene and play their instruments.

Here, the commentators come to our help to explain the symbolism. Vallabhacharya says that the pleasure-seeking sense organs are the heads of the snake. When people seek pleasure at the expense of others by hurting others, they are poisonous. They bind a person in the cycle of birth and death. Such senses are the multiple heads of the snake, and hence, Krishna jumps from one hood to another while holding the tail in one hand. This is the beautiful image we see in the story.

When bhakti enters the mind, there is an initial resistance, and that is what Kaliya’s actions signify. Slowly, Krishna subdues one head after another, and the snake falls unconscious, vomiting poison.

At this juncture, the wives (buddhi, the thinking power) of Kaliya enter the scene. When the ego gets into trouble, its wife, buddhi, awakens. It thinks of a higher power. The wives of the snake pray to the lord, accepting his mistakes. Their prayer is one of the beautiful passages in the Bhagavatam. It is a prayer to the Supreme Reality manifest in all beings. Krishna orders the snake to leave the lake, and Kaliya does so, signifying that the old, poisonous ego has gone. We can take it that the subdued ego is no longer hurting others, and the waters become pure. Now, all boys and cows can drink the water. It means that the person is friendly to all beings.

Many stories from puranas are such that even a child enjoys the action part of the story. An adult adores the benevolent nature of the lord. But, a mature student sees the struggle and effort in the mind of the seeker for inner growth.