Cries of abuse in Catholic church start to be heard in Japan

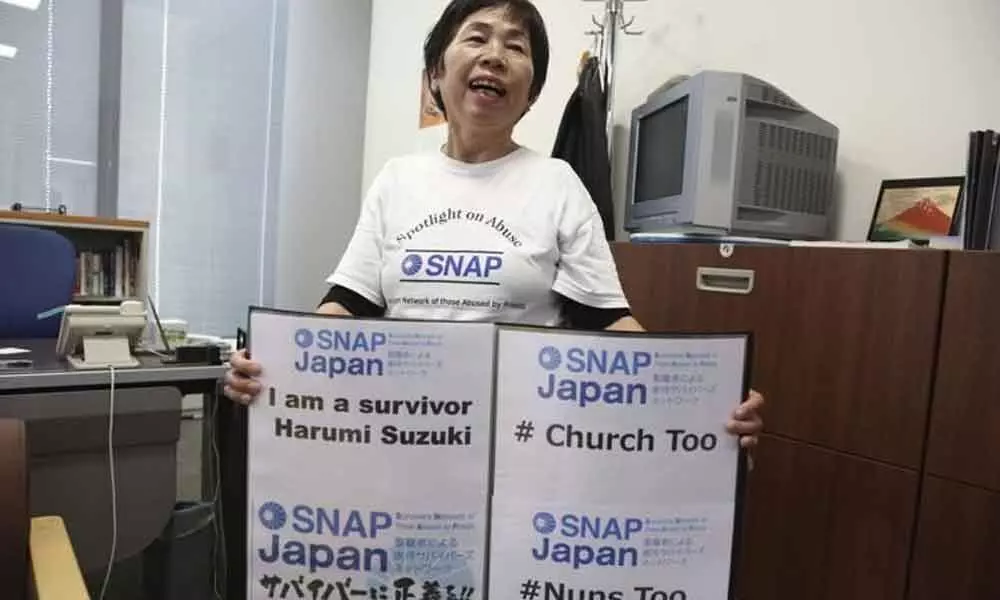

During Pope Francis' recent visit to Japan, Harumi Suzuki stood where his motorcade passed by holding a sign that read: “I am a survivor.”

During Pope Francis' recent visit to Japan, Harumi Suzuki stood where his motorcade passed by holding a sign that read: "I am a survivor." Katsumi Takenaka stood at another spot, on another day, holding up his banner that read, "Catholic child sexual abuse in Japan, too."

The two are among a handful of people who have gone public as survivors of Catholic clergy sexual abuse in Japan, where values of conformity and harmony have resulted in a strong code of silence.

But as in other parts of the world, from Pennsylvania to Chile, Takenaka and Suzuki are starting to feel less alone as other victims have come forward despite the ostracism they and their family members often face for speaking out.

Their public denunciation is all the more remarkable, given Catholics make up less than 0.5% of Japan's population. To date, the global abuse scandal has concentrated on heavily Catholic countries, such as Ireland, the U.S. and now, many countries in Latin America.

All of which could explain why the Catholic hierarchy in Japan has been slow to respond to the scandal, which involves not only children being sexually abused but adults in spiritual direction — an increasingly common phenomenon being denounced in the #MeToo era.

In a recent case, police were investigating allegations by a woman in Nagasaki, the region with the greatest concentration of Catholics in Japan, that a priest touched her inappropriately last year.

Japanese media reports said the woman had been hospitalized for PTSD. Police confirmed an investigation was underway but the church declined to provide details, citing privacy concerns.

The Catholic Bishops' Conference of Japan launched a nationwide investigation into sexual abuse of women and children this year, responding to the Vatican's demand for an urgent response to the global crisis.

The results haven't been disclosed, and it's unclear when they might be ready. Similar studies have been carried out by the U.S., German and Dutch churches, with the findings made public, and government-mandated inquiries have devastated the church's credibility in countries like Australia and Ireland.

The Japanese bishops' conference has said it carried out various investigations since 2002, but the names of the accused, the nature of the allegations or any other details have never been released.

Broadcaster Japan News Network said 21 cases were found in the latest investigation. The conference declined to confirm that number. It's unclear whether that intcludes decades-old cases like Takenaka's and Suzuki's.

In a rare case of the church taking action, Takenaka received a public apology earlier this year from Nagasaki Archbishop Joseph Mitsuaki Takami for the sexual abuse he suffered as a child at the Salesian Boys' Home in Tokyo, where he was placed after his parents' divorce.

"I think his apology was sincere in his own way. But the response has lacked a sense of urgency, and there is no sign they will take any real action," Takenaka told The Associated Press.

Takenaka's alleged perpetrator was a German priest, who he said initially took off the boy's clothes to examine bruises from beatings he suffered from other boys at the home.

The priest's examinations escalated to fondling and other sexual acts, which went on for months until the priest was transferred, he said.

He reported that the priest told him he would go straight to hell if he told anyone and gave him candy and foreign stamps. Takenaka identified his abuser as the late Rev. Thomas Manhard.

The Salesians in Munich confirmed Manhard had worked in Japan from 1934-1985, when he returned to Germany. He died a year later. Spokeswoman Katharina Hennecke said the order had no information in its records about allegations against him. Takenaka's account was confirmed by the Rev.

Hiroshi Tamura, who runs the Salesian Boys' Home and said he was conferring with the Japanese bishops' conference to work out a response to his claim.

Takenaka, a civil servant in his 60s, said the church needs to be proactive in disclosing details about the abuse it has uncovered, identifying offending clergy and how they were penalized. He said an outside investigation is needed and a forum for victims to come together.

"The victims are isolated," Takenaka said. "No one knows for sure if the abuse is still going on." Pope Francis has emphasized the global nature of the abuse problem, summoning bishops conference leaders from around the world to the Vatican this past February and passing a new law requiring all cases be reported to church authorities.

Associated Press