Ashokan Edicts And Visionaries Spread Messages Of Tolerance And Peace

Ashokan Edicts And Visionaries Spread Messages Of Tolerance And Peace

- Due to his geographical conquests and the messages of tolerance he preached throughout his expanding kingdom, he has come to be hailed as one of the most exemplary monarchs in world history.

- The discovery of another inscription in 1915, in which the Emperor identified himself as 'Ashoka Piyadasi,' made this conceivable.

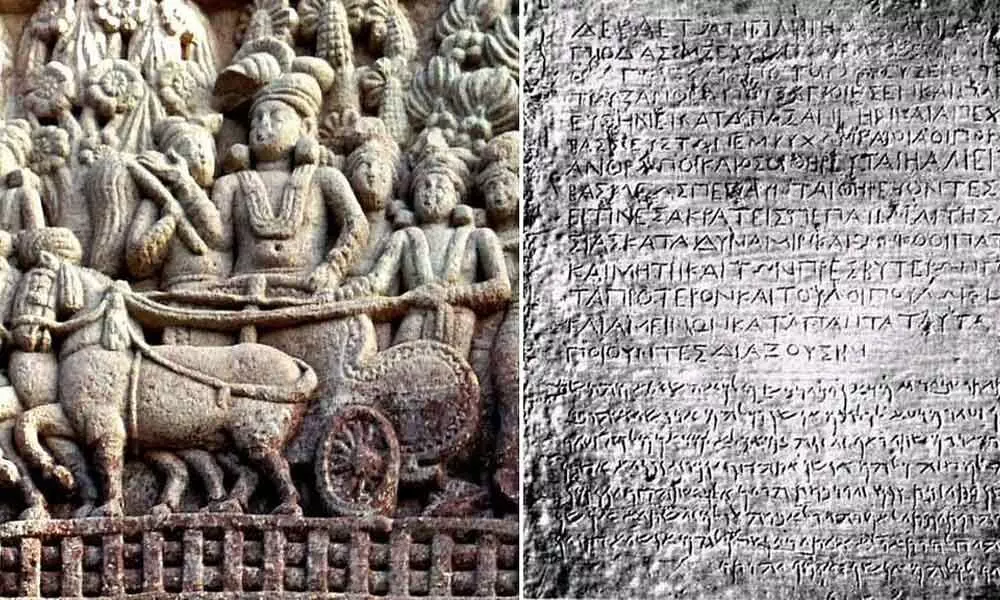

Few lines are engraved for posterity on a big grey boulder in Pakistan's windswept Khyber valley. 'Doing good is hard – Even beginning to do good is hard.' These are the words of Ashoka, the third Mauryan monarch, who ruled over one of South Asia's largest, most cosmopolitan, and powerful empires. Due to his geographical conquests and the messages of tolerance he preached throughout his expanding kingdom, he has come to be hailed as one of the most exemplary monarchs in world history.

Ashoka also fostered a philosophy of mutual respect and tolerance for individuals of different religions through his edicts. He writes in his 7th edict explaining that the king intends that all traditions should exist everywhere.

Without the discovery of the Ashokan edicts in the 19th century, these visionary ideas and the humanitarian ethics of Emperor Ashoka would have remained forgotten. Till the edicts were interpreted by Orientalist scholar James Princep in 1837, Ashoka was just an ancient Indian rule and emperor like others but everything changed when scholars realized what his inscriptions meant. Surprisingly, when Princep began deciphering the edicts, no one knew who the author was. The original inscription did not mention Ashoka, instead referring to 'Piyadasi', referring t 'Beloved of the Gods. It required the world more than seven decades to realize that Ashoka was Piyadasi. The discovery of another inscription in 1915, in which the Emperor identified himself as 'Ashoka Piyadasi,' made this conceivable. Though many of these rock faces have since disintegrated, Ashoka's message can still be found on rocks all around India, from the Khyber Pass to South India.

To comprehend Ashoka's lessons, people must first grasp the remarkable story of transformation that preceded them - a history that begins eight years after Ashoka's accession to power, in 270 BC. Ashoka's first battle after becoming emperor was an invasion of Kalinga, an autonomous feudal state on India's east coast. The triumph gave him a wider dominion than any of his forefathers, but it came at a high price. According to historical accounts, the Kalinga was one of India's worst conflicts, with 100,000 to 300,000 people.

Observing the massacre and the great suffering that ensued took a toll on Ashoka's emotions. In Rock Edict 13, the distraught emperor denounced military conquest and murder, writing that he was much grieved by the slaying, dying, and expulsion of captives that occur when an unconquered land is subjugated. He abandoned the predatory foreign strategy that had previously defined the Mauryan empire in favour of a policy of peaceful coexistence. 'The roar of the drums of battle has been replaced by the music of ethics,' Ashoka says in his own iconic words inscribed on the 4th edict.

A changed Ashoka wanted to communicate his new outlook on life by carving words into freestanding rocks and massive stone pillars throughout the empire and along major trade routes. He wished for his words to encourage individuals of all ages. The inscription on ethics has been inscribed in stone so that it may endure long and that my descendants may act in accordance with it, Ashoka declares at the end of the 5th rock edict.

He also wanted them to encourage people from many communities and areas. As a result, his edicts are not limited to a single language or location. To ensure that his communications were widely understood, Ashoka wrote them in vernacular languages such as Brahmi and Kharoshti rather than Sanskrit.

Building great roads connecting vital trade centers, planting trees along with them for shade, developing mango groves, botanical pharmacies, restrooms, and even hospitals for humans and animals are all part of Ashoka's public works. Ashoka went on frequent inspection tours to ensure that these initiatives were carried out, and he expected his bureaucrats to do the same. His legacy of responsible statehood, tolerance, and generosity is etched in India's rocks even now. As a result, it's probably natural that India's new flag features an Ashokan emblem, the Ashok Chakra. This ancient Indian emperor's goal of a humanitarian society should be remembered by modern India.