Live

- Chanchalguda Jail Officials Say They Haven't Received Bail Papers Yet, Allu Arjun May Stay in Jail Tonight

- BJP leaders present evidence of illegal voters in Delhi, urge EC for swift action

- Exams will not be cancelled: BPSC chairman

- Nagesh Trophy: Karnataka, T.N win in Group A; Bihar, Rajasthan triumph in Group B

- YS Jagan condemns the arrest of Allu Arjun

- Economic and digital corridors to maritime connectivity, India and Italy building vision for future, says Italian Ambassador

- SMAT 2024: Patidar's heroics guide Madhya Pradesh to final after 13 years

- CCPA issues notices to 17 entities for violating direct selling rules

- Mamata expresses satisfaction over speedy conviction in minor girl rape-murder case

- Transparent Survey Process for Indiramma Housing Scheme Directed by District Collector

Just In

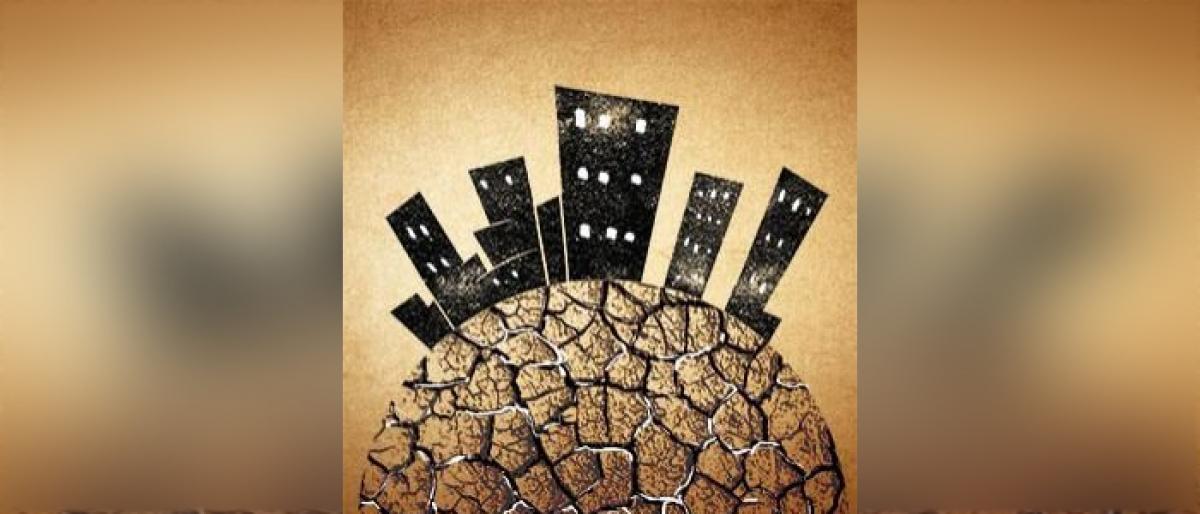

Cauvery and Cape Town—one a river flowing through agricultural fields and booming cities in south India and the other a modern and prosperous city in South Africa—have much in common. Let’s make the connection. Cape Town is on notice that the day when its water will run out is very close.

Cauvery and Cape Town—one a river flowing through agricultural fields and booming cities in south India and the other a modern and prosperous city in South Africa—have much in common. Let’s make the connection. Cape Town is on notice that the day when its water will run out is very close.

Already, the city is reeling under a water emergency, with politicians asking citizens not to flush or water plants. The question that Cape Town is facing is how will it manage its water more prudently—how will it ensure that the water is supplied to all and the sewage that leaves homes after supply is reused and recycled?

Can Cape Town do this? Can it live with its water endowment? Or will it do what all cities try and do—pipe more water from its surroundings or buy its way into ‘new’ water by desalinating seawater. But will this mean that the cost of water will go up and so will it spend more to supply to all, including its poor? Will it then have the funds to treat sewage? These are critical questions.

And this is where we must make the link with Cauvery. The February 2018 Supreme Court (SC) decision on allocation of Cauvery water provides closure to an age-old conflict. But it also raises some inconvenient questions, which will determine how cities manage water prudently and wisely.

The SC has argued that the city “is the seat of intellectual excellence particularly in terms of information technology and commercial flourish.” So, instead of the 1.75 thousand million cubic feet (TMCFT) allocated to the city by the Tribunal, the SC has allocated 6.5 TMCFT.

The Tribunal, in its calculation of Bengaluru’s water allocation, had used the following principles. One, that the city would get only as much allocation as its “rightful” share—only one-third of the city fell within the Cauvery basin, and so, only one-third of its water demand would be met from the river.

The SC has overturned that, arguing that cities like Bengaluru deserve more water regardless of their location. Therefore, it has, in effect, agreed that cities have the “right” to trans-boundary water supply.

The second principle established by the Tribunal was that groundwater—replenished through natural recharge, stream flow and through lakes and reservoirs—would meet 50 percent of the city’s water demand. Only 50 per cent would be allocated from the river. But the SC has dismissed this saying, “this assumption is unacceptable.” This is extremely unfortunate.

The fact is Bengaluru is a classic case of a city that is deliberately and willfully destroying its lakes. These were the sponges of the city, which would recharge groundwater and allow it to build on its rainwater endowment. Now, the SC has, in effect, said that the city does not need to bother about its lakes as it does not need to depend on groundwater for its water supply.

Instead, what should have been demanded is that the city first uses its own local water sources and only meets the deficit from the imported and transported Cauvery water. This would also be important as the transportation of Cauvery water is already bleeding the city and making water so costly that more and more people are switching to groundwater. So, it is a double whammy.

The city will disregard its local water sources and its people will have no option but to extract—overuse this source. Be clear, Bengaluru has not gained from this allocation. It will lose, whatever its politicians say today.

The third principle—this one upheld by the SC—is that the city’s water demand will be calculated only at 20 per cent. In other words, this is what the city “consumes”. The remaining 80 per cent of the water that is demanded and supplied is discharged in terms of waste. It is not consumed. This means that the city has to plan now deliberately to take back this sewage water and to treat it, clean it and reuse it.

This is where all water sums are going wrong. Tamil Nadu, the state downstream and Chennai, the other metropolis at the end of the Cauvery waterline, complained that Karnataka is not giving it water, only sewage. And this is where Bengaluru will have to change.

The SC has also said that drinking water will get the highest priority in terms of allocation—it will be prioritised over the demand of water by agriculture and food. This portends for new water conflicts. We have to remember that in countries like India, a vast number of people still get their employment from agriculture and so water is used in rural areas.

But in the west, where people have moved away from agriculture and indeed moved away from rural to urban, water is used in cities and industries. All in all, as I said, not much difference. Cape Town, Bengaluru and Chennai, all have a common present. The question is if they can create a new future that is water-secure because it is water wise.

By: Sunita Narain

(Courtesy: Down To Earth of which the writer is the Editor)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com