Dr Ahluwalia is right: Future generations must learn from PV’s reform legacy

He stressed that carrying forward Rao’s reform legacy requires a conscious strengthening of cooperative federalism. He observed that economic transformation in India cannot be driven by the Centre alone and that effective coordination and trust between the Union and the States are essential for sustaining reforms. Rao intuitively understood this balance and governed with respect for India’s federal diversity, a lesson that remains central to India’s future economic progress

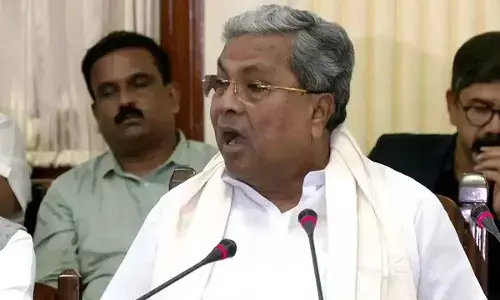

In his recent PV Narasimha Rao Memorial Lecture delivered in Hyderabad, Dr Montek Singh Ahluwalia reflected on PV’s enduring legacy, not merely as a reformer of the past, but as a statesman, whose approach to leadership, economic management, and political courage remains deeply relevant for India’s future. He emphasiszed that PV’s greatness lay not in isolated decisions but in his ability to combine political realism with intellectual openness at a moment of national vulnerability.

Dr Ahluwalia began by recalling the extraordinary circumstances of the 1991 balance-of-payments crisis, and how PV’s leadership during that period demonstrated calm resolve rather than panic. He highlighted that the economic reforms were not an abstract ideological shift but a practical response to crisis, undertaken with full awareness of political risks. In this context, he drew attention to the decisive choice of Dr Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister, noting that this partnership was foundational to India’s reform trajectory.

He referred to the ‘PV–Manmohan combination’ as a rare and powerful mix, suggesting that India’s future leadership would require a similar blend, a ‘PV–Manmohan mix’ combining political courage, intellectual depth, administrative discipline, and ethical seriousness. According to him, sustaining and advancing the PV legacy would demand leaders who can understand the compulsions of politics and the rigour of sound economics, rather than privileging one at the cost of the other.

Reflecting on the human and political pressures of the reform period, Dr Ahluwalia recalled the Harshad Mehta episode and the turbulence it caused in financial markets and public discourse. He maintained that this episode was a reminder of how fragile confidence was during the early reform years and how leadership had to navigate not only economic uncertainty but also political and institutional shock, which called for robust financial oversight and institutional credibility alongside liberalization.

In one of the most personal and revealing segments of the lecture, Dr Ahluwalia referred to the moment when Dr Manmohan Singh offered his resignation as Finance Minister and reportedly stopped attending office for two days, following political attacks linked to the market crisis. PV’s intervention at that moment was decisive, he pointed out.

Ahluwalia highlighted Rao’s instinct for institution-building and federal balance, observing that many reforms succeeded because they were implemented with sensitivity to India’s federal structure.

He stressed that carrying forward Rao’s reform legacy requires a conscious strengthening of cooperative federalism. He observed that economic transformation in India cannot be driven by the Centre alone and that effective coordination and trust between the Union and the States are essential for sustaining reforms. He noted that Rao intuitively understood this balance and governed with respect for India’s federal diversity, a lesson that remains central to India’s future economic progress.

In fact, a day earlier I was with him in a small gathering of well-wishers, purely as an informal circle of achievers from diverse specializations.

When I presented my book Democracy and Governance through Lens and Blurred Glasses: A Journey into Distorted Visions of Modern-Day Politics, he did not leaf through it casually but enquired whether there is any reference to Narasimha Rao in the book. The episode involving PV while he was Chief Minister and his Chief Secretary Valluri Kameswara Rao, an eminent ICS officer, attracted his attention as an example of the moral courage of a role-model civil servant and the humility of a Chief Minister of that era.

During the conversation, he recalled Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s civilizational grace that transcended party lines and Rajiv Gandhi sending Vajpayee abroad for medical treatment. Responding to changing the name of MGNREGA as VB–G RAM G, he remembered Sharad Yadav and spoke of a time when rural employment was treated as a moral responsibility.

Being candid about liberalization, he made it clear that what we see today is not what Rao had envisioned. Stressing that institutions must remain central, Dr Ahluwalia felt that India needs strong, independent, and uncaptured regulators in every field. He cited TN Seshan’s uncompromising tenure at the Election Commission as an example of institutional courage.

Coalition governments, despite instability, at least introduced checks and balances, he observed. On the current political leadership, his assessment was measured. He noted that one significant shift had been the breaking of an old elite monopoly in politics. That opening question about PV to me was not simply about a reference in a book, but about whether democracy is still understood as a delicate balance of courage, humility, and institutional respect. It reaffirmed that democracy lives not in proclamations, but in quiet moments when power pauses to listen, and that these moments, if remembered, still have the capacity to guide.

The former Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission maintained that remembering PV should go beyond ceremonial homage. The real tribute lies in nurturing leadership that reflects PV’s temperament, intellectually open, politically pragmatic, institutionally respectful, and morally anchored, and in ensuring that the reform spirit he ignited continues to evolve in response to India’s changing challenges.

Turning to the question of legacy transmission, Dr Ahluwalia made a distinctive suggestion that PV Narasimha Rao’s life and reform journey should be presented to younger generations in an accessible narrative form, explicitly referring to the ‘Amar Chitra Katha’ model. He argued that Rao’s contributions, particularly the story of reforms, deserve to be taught not merely as dry policy history but as a compelling national story of courage, intellect, and quiet determination. Such inclusion in educational curricula, he felt, would help correct historical neglect and inspire future generations to appreciate the complexity of nation-building.

What distinguishes Dr Montek Singh Ahluwalia is not merely his resume, but his temperament: a rare blend of analytical clarity and civil restraint. He listens first, speaks later, and when he does, it is without performance.