Rethinking design evaluation in a digital-first era

Why prototyping and digital making deserve a place in entrance exams

For decades, entrance exams for design, architecture, and engineering programs have prioritized drawing ability, theoretical knowledge, and problem-solving on paper. These skills remain important. But the nature of design work has changed fundamentally. Today’s designers do not stop at sketches or concepts, they are expected to translate ideas into tangible, testable forms using digital tools. In an era where hybrid making defines professional practice, it is time to ask a provocative but necessary question: should entrance exams test basic prototyping and digital making skills?

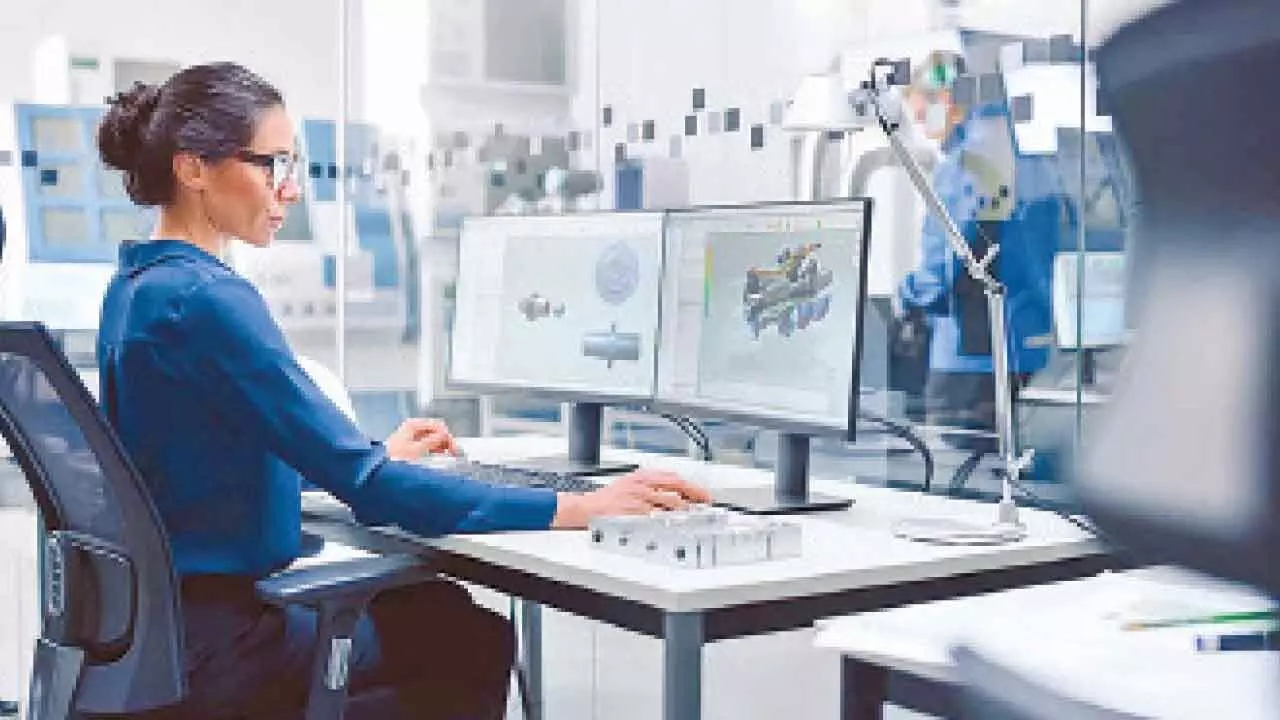

Design careers, these days, sit at the intersection of creativity, technology, and fabrication. Industrial designers routinely move between CAD software and rapid prototyping machines. UX designers collaborate with developers using interactive prototypes rather than static wireframes. Architects simulate structures digitally before a single brick is laid. Even product managers and entrepreneurs are expected to understand how digital prototypes work to communicate ideas effectively. The gap between “idea” and “making” has narrowed and education systems must reflect that reality from the very first gatekeeping moment.

Testing basic prototyping skills does not mean expecting applicants to be expert machinists or professional coders. Rather, it means assessing whether students can think through making. Can they convert a rough idea into a simple 3D model? Do they understand scale, constraints, and iteration? Can they use accessible tools, basic CAD software, laser cutting workflows, or simple digital mockups to express intent? These are foundational skills, not advanced specializations.

Critics argue that such testing would unfairly advantage students with access to expensive labs, 3D printers, or elite schools. This concern is valid, but solvable. Digital making does not have to be hardware-heavy. Free and widely available tools prototyping platforms allow students to demonstrate spatial thinking and process without costly infrastructure. Entrance exams can focus on reasoning, workflow, and decision-making rather than polished outputs. A low-fidelity prototype often reveals more about thinking than a perfect rendering.

In fact, incorporating prototyping into entrance exams could democratize evaluation rather than restrict it. Traditional drawing-based tests often privilege students with years of formal coaching. Digital tools, by contrast, are increasingly self-taught, explored through online tutorials, open-source communities, and experimentation. A student from a small town who has learned CAD from YouTube and built simple models at home may be better prepared for contemporary design practice than one trained solely in exam-oriented sketching.

Another argument against testing digital making is that entrance exams should assess “potential,” not “training.” But prototyping is not merely a trained skill, it is a way of thinking. The act of making forces candidates to observe details, confront constraints, iterate on failure, and balance imagination with feasibility. These qualities are at the heart of good design learning. A simple task, such as modeling a functional object with given constraints or creating a basic interactive flow can reveal adaptability, logic, and creative problem-solving more effectively than multiple-choice questions.

Importantly, testing prototyping skills would send a powerful signal about what institutions value. It would communicate to students that design is not just about aesthetics or theory, but about building, testing, and refining. This alignment between admissions and curriculum can reduce the shock many first-year students experience when confronted with fabrication labs and software-intensive courses. It prepares them mentally for a learning environment rooted in experimentation.

That said, digital making should complement, not replace traditional assessments. Drawing, observation, and conceptual reasoning remain essential. The goal is balance. A hybrid entrance exam model that combines sketching, problem-solving, and basic prototyping would better reflect the multidisciplinary reality of contemporary design careers.

As industries continue to blur the lines between designer, technologist, and maker, education systems must evolve accordingly. Entrance exams are not just filters; they are statements of intent. By testing basic prototyping and digital making skills, institutions can ensure they are admitting students ready to move from concept to code and from ideas to impact.

(The author is Director, Institute of Design at JK Lakshmipat University)