Live

- Gali Janardhana Reddy announces gold-plating of Anjaneyaswamy Temple tower

- Private practitioner found operating from govt clinic

- PM stresses on thinking out-of-the-box in every sector

- Lokayukta cracks down, seizes illicit assets worth crores

- Farmers protest over delay in canal repair

- Amid continuing furore, five more maternal deaths occur in State

- Fostering a robust innovation

- New AP tourism policy hailed

- Village that gave land for Suvarna Vidhana Soudha, a picture of apathy

- What’s The Matter At Hand?

Just In

Athletes might perform better when reminded of something a bit grim -- their impending death, suggests new research from the University of Arizona in the US.

Death-related prompts may enhance athletes' performance

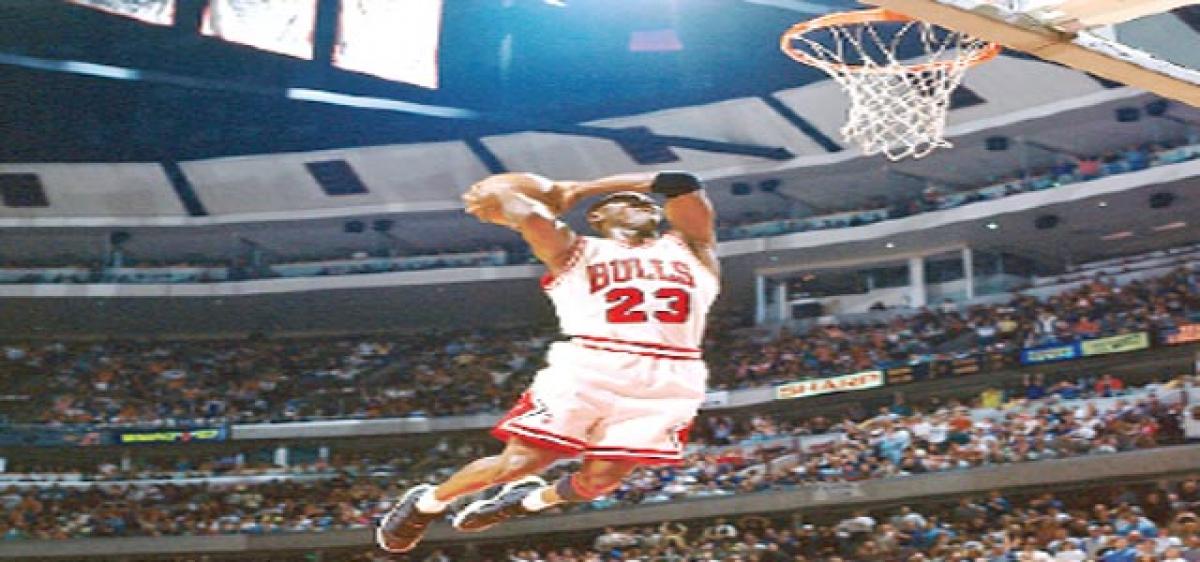

Athletes might perform better when reminded of something a bit grim -- their impending death, suggests new research from the University of Arizona in the US. The researchers found that basketball-playing participants scored more points after being presented with death-related prompts, either direct questions about their own mortality or a more subtle, visual reminder of death.

The improved performance is the result of a subconscious effort to boost self-esteem, which is a protective buffer against fear of death, according to psychology's terror management theory. "The theory talks about striving for self-esteem and why we want to accomplish things in our lives and be successful," explained co-lead investigator of the research Uri Lifshin.

"Your subconscious tries to find ways to defeat death, to make death not a problem, and the solution is self-esteem," he said. Participants in the studies were male college students who indicated that they enjoy playing basketball and care about their performance in the sport. None of them played for a formal college basketball team.

"When we're threatened with death, we're motivated to regain that protective sense of self-esteem, and when you like basketball and you're out on the basketball court, winning and performing well is the ultimate way to gain self-esteem," Lifshin said. While it may seem strange that something as dark as death could be motivating, coaches have in some ways intuitively known this for years, the researchers noted.

And while the researchers looked specifically at basketball, they think the effects are not limited to sport. "There's no reason why it shouldn't work in soccer as it does in basketball. We don't believe this is sport-specific and we don't believe this is gender-specific," Zestcott noted. (The findings will be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology.)

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com