Live

- Bejan Daruwalla’s horoscope

- Study warns: Ultra-processed foods may accelerate biological age

- CM pledges more political opportunities to Madigas

- Vizag attracts tourists as much as Kashmir

- Year-Ender 2024 Guide: Home remedies to relieve Period Pain.

- All India crafts mela begins today

- TTD gears up for Vaikunta Ekadasi fete

- Express Yourself

- Rajadhiraaj: Love. Life. Leela

- Students immerse in nature in Chilkur forest

Just In

A long-running Indian TV game show about a group of disparate people consciously living under the continuous view and direction of an omniscient but unseen observer may make for entertainment for some but should actually warn of technology\'s capacity to intrude into all aspects of human life. Much more so if used by the state to stifle dissent and instill conformity - as warned by a great writer

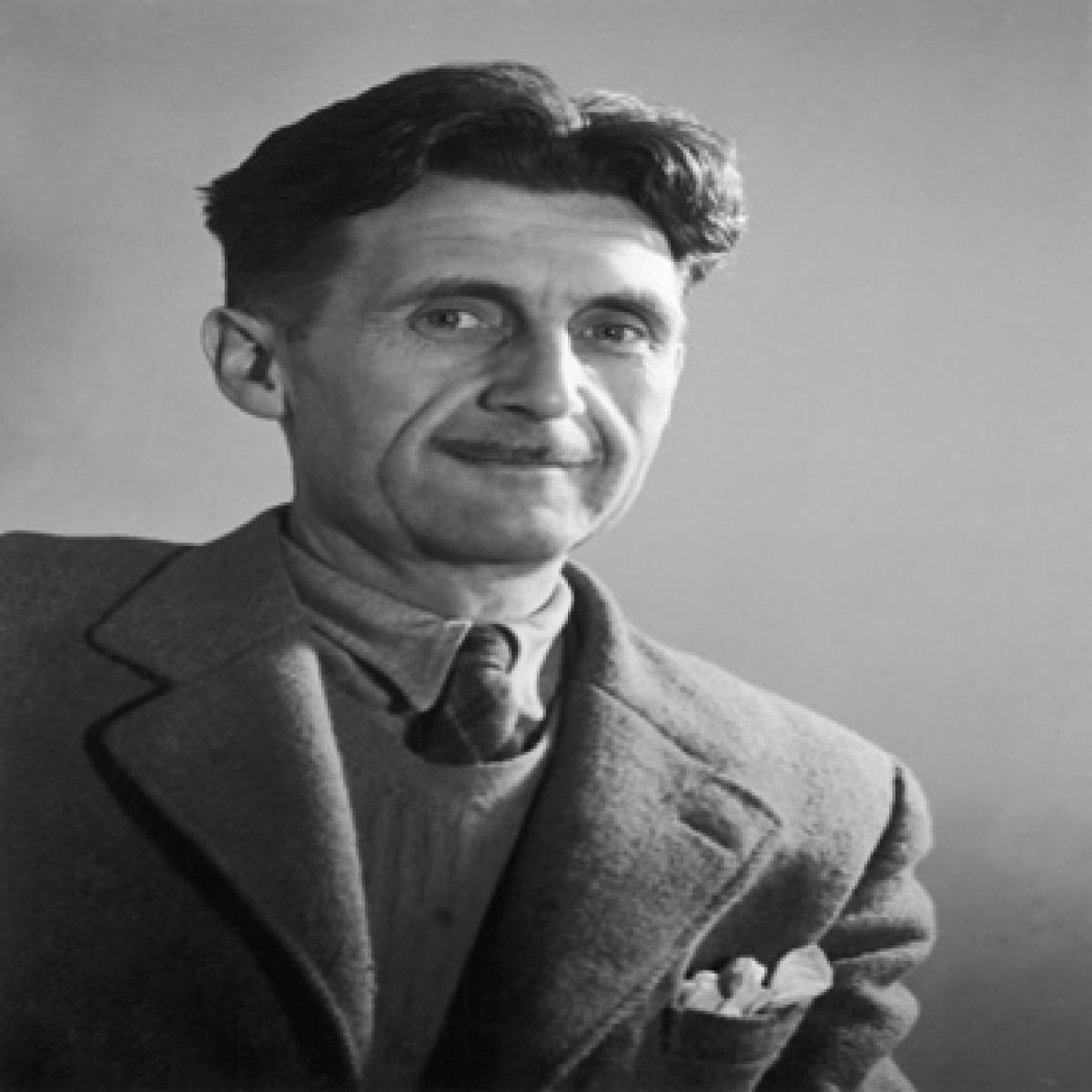

Prolific author George Orwell predicted today's nightmares decades ago in his books

A long-running Indian TV game show about a group of disparate people consciously living under the continuous view and direction of an omniscient but unseen observer may make for entertainment for some but should actually warn of technology's capacity to intrude into all aspects of human life. Much more so if used by the state to stifle dissent and instill conformity - as warned by a great writer whose one dire creation was used as the name of the original British version.

But ‘Big Brother’ was not George Orwell's only contribution to culture, politics and society but just one of his newly-created words and terms - cold War, thought police and thoughtcrime ("Thoughtcrime does not entail death, thoughtcrime is death"), doublespeak and unperson - that continue to have significant resonance even more than six decades after he coined them. Especially, for our country in present times.

Unlike monarchs and statesmen who can acquire immortality simply by their names becoming an adjective used to refer to their era, those in the cultural realm must earn it by pioneering a new style or enduring creations that awe, inspire, regale or warn - and Orwell's acquired it through the latter reason's last criterion.

Like Dickensian connoting the poor social conditions of the author's times, or Kafkaesque for surreal and disorienting situations or somewhat menacingly complex authority, Orwellian is also not very positive with its connotations of regime control and governance through propaganda, surveillance, misinformation, a cultish infallible leader, a scapegoat and/or external enemy and manipulation of the past - all designed to curb freedom and individuality.

But, Orwell, the pen name of Bihar-born Eric Arthur Blair (1903-50) and most atypical middle-class Englishman, needs to be seen through a wider prism than his last two - though most famous - works. And neither should ‘Animal Farm’ (1945), an allegorical account of how revolutions can get subverted and ‘1984’ (1949), set in a dystopian future where an authoritarian state does its best to stamp out individual thought and foster blind conformity and adoration of leaders, be dismissed as just referring to Stalinist Soviet Russia, due to the superficial resemblances.

Let alone his other longer works of social satire or his non-fictional accounts of poverty and deprivation and internecine infighting on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War, Orwell's best writings are his lucid essays. These span a wide gamut of political, social and literary issues, from witnessing the taking of life or performing the act oneself to the travails of a book reviewer, and from that unique English affectation - making the perfect cup of tea - to a vividly evocative description of the spring season to defending PG Wodehouse, in trouble for 'propaganda' broadcasts for Germans early in the Second World War, and a penetrating analysis of his works.

But those that stand out are on nationalism and language and its relation to politics and both remain as, if not more, relevant today as when he wrote them in the 1940s. In ‘Notes on Nationalism’ (published in October 1945), Orwell makes a compelling case that it is based on abandoning common sense and facts, with it has the "habit of assuming that human beings can be classified like insects and that whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled 'good' or 'bad'," and secondly, it entails "the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil..."

He, however, stresses it be not confused with "patriotism", which is "devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people" and by "its nature defensive, both militarily and culturally" while nationalism is "inseparable from the desire for power". His examples may be dated but the principles remain valid.

Likewise, in ‘Politics and the English Language’ (April 1946), he postulates a link between bad prose and oppressive ideologies, and how "political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible", such as (for then) "continuance of British rule in India". Since the brutal language such a defence will entail will be unpalatable, it necessitates "political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness". We are all too familiar with it for decades now.

Orwell also divined measures that could divert attention of the masses - "films oozing with sex" and "rubbishy newspapers containing almost nothing but sport, crime and astrology" (as per ‘1984’). It would have been interesting to know what he would have made of social media and handheld communication and entertainment devices.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com