The Magical Tale of Three Cities

Jaded and done to death, as a medium, cinema, today, which is a little over a century old, finds it difficult to spring a surprise. And, yet every now and then something magical comes along and leaves you spellbound when you are least expecting.

Jaded and done to death, as a medium, cinema, today, which is a little over a century old, finds it difficult to spring a surprise. And, yet every now and then something magical comes along and leaves you spellbound when you are least expecting.

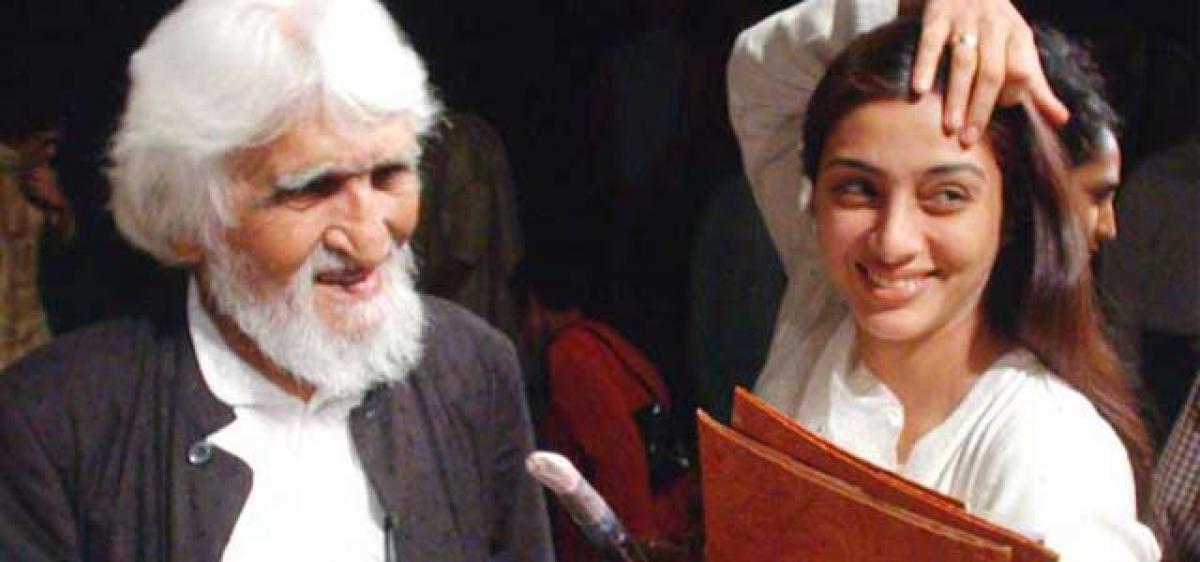

One of the films that not only remains an underrated, and even under-discussed, gem but could very well fall into the magical category is M. F. Husain’s ‘Meenaxi: A Tale of Three Cities’ (2005).

Made when Husain was 90-years old, ‘Meenaxi’ was a failure at the box office and even mocked for being a show-reel of sorts for a bunch of people that included composer AR Rahman, cinematographer Santosh Sivan, editor Sreekar Prasad, art director Sharmishta Roy and modern dance exponent Astad Deboo and Odissi artist Ileana Citaristi.

The film also courted controversy when a qawwali penned by Husain himself, Noor-Un-Ala-Noor, was targeted by Islamic groups led by All India Muslim Council for including a line inspired by a quote from the Quran.

Following protests Husain withdrew the film within days of its release, which was unfortunate for it devoid viewers to perhaps discover a film that was nothing less than a pure cinematic experience.

‘Meenaxi: A Tale of Three Cities’ begins with a beleaguered Hyderabadi writer, Nawab (Raghuveer Yadav), struggling with a classic writer’s block. It has been five years since his last book came out and everywhere he goes people seem to be asking the one question that he dreads- when is the next book out?

At a family wedding, Nawab bumps into Meenaxi (Tabu), a self-obsessed perfumer seller in Hyderabad and she dares Nawab to use her as a muse to finally get around writing his novel. Meeting Meenaxi ignites Nawab and he tries to get close to her and while she spends time with him she couldn’t care less for being his muse.

Bustling with new ideas ever since Meenaxi stepped into his life, Nawab forges ahead and starts writing the story. He sets the tale in Jaisalmer and also includes the local foul-mouthed mechanic (Kunal Kapoor) for good measure.

Meenaxi keeps mocking Nawab and with each step Nawab begins to get lost in the labyrinth that he creates. Fed up with Meenaxi’s constant bickering when, in the book, things start getting boring in Jaisalmer, Nawab turns the story around and sets it Prague.

Here Meenaxi is Maria, an orphan, the mechanic becomes Kameshwar. The Meenaxi obsessed Nawab, too, keeps slipping in and out of the story. At some point, the roles switch and Meenaxi starts dictating what would happen next. She mocks Nawab and he plummets further into despair.

The line between reality, myth, dream, and fiction blur with Nawab dying before finishing his work. But is he dead in the book or in reality? Is Meenaxi really there or is it just Nawab’s personification of the ultimate woman?

‘Meenaxi’ might be a tad too experimental for most but as a film, it remains a lost masterpiece that perhaps suffered thanks to the reputation that preceded it.

Being a follow-up to the uber experimental ‘Gaja Gamini’ (2000), a thematic film that envisioned Madhuri Dixit as a manifestation of womanhood seen from the artist’s eyes, ‘Meenaxi’ in spite of a comparatively more traditional structure of a story besides the theme, was dismissed even before being given a fair chance.

It was not like ‘Meenaxi’ was not self-indulgent as a film – after all, the narrative seems to be just an excuse for the painter-filmmaker to celebrate the three cities he loved the most – but in a departure from the template that he used in ‘Gaja Gamini’, Husain evoked the uniqueness of the three locations and merged them wonderfully well with the narrative.

Being an artist Husain is someone who knows the mysterious ways inspiration ends up working in. The moment the narrative introduces us to Nawab and the power his pen ostensibly wields, it immediately undercuts him by pitting him against Meenaxi, who is supposed to be the muse but ends up being a shrewd manipulator.

But the space that Husain truly scores in is in the manner he visually interprets the concept of dissonance between a creator and the creation. In an interview given to a newspaper when the film came out, cinematographer Santosh Sivan put the notion of Husain making a film after ‘Gaja Gamini’ in an interesting perspective.

He mentioned that when someone of M.F. Husain’s eminence makes a film, “he is under no compulsion to do anything other than what comes from within.” It is this aspect that cuts across ‘Meenaxi’ in all departments and the result is the sheer brilliance of storytelling in a form that comes alive for all senses.