Like Father, unlike Son

There were very rare occasions when children overrule their fathers edicts Some regard the reason for such a rare tradition as the respect that the former possess for latters sacrifices and others regard it as a mark of fear, as father is regarded as the first master of his children

There were very rare occasions when children overrule their father’s edicts. Some regard the reason for such a rare tradition as the respect that the former possess for latter’s sacrifices and others regard it as a mark of fear, as father is regarded as the first master of his children.

Before I start writing on the recent instance where a gentleman with utmost scholarship and wisdom, and with no less respect for his father, overruled his father’s pronouncements, on multiple occasions, it would only be prudent on my part to cite a famous adage: The pen is mightier than the sword and a judge’s pen is far mightier than anyone else’s pen.

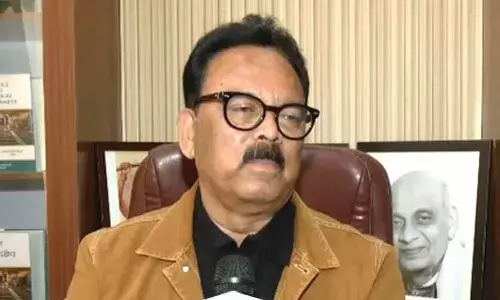

Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, an incumbent Judge of the Supreme Court of India was named in the headlines of myriad newspapers in recent days for his dissenting judgment in the Aadhaar case and for his majority pronouncement on adultery.

Late Justice Yeshwant Vishnu Chandrachud, father of Justice D.Y.Chandrachud, a retired judge of the Supreme Court of India had to face immense criticism for two landmark verdicts pronounced by the Supreme Court of India.

The first is the 1976 ADM Jabalpur case, famously known as Habeas Corpus case. In this case a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court had held that none can approach courts challenging the abrogation of their personal life and liberty when the Emergency was in operation.

The Supreme Court applied the doctrine of procedure established by law and held that Article 32, the right to approach the Supreme Court of India for infringement of fundamental rights, remains suspended during the times of emergency.

The Supreme Court in this infamous case has overruled the pronouncements of nine High Courts and, regrettably, ruled in favour of the dispensation of that day which invoked Article 352 of the Constitution of India and imposed national Emergency on the ground of prevailing internal disturbance in the country.

The verdict of the Supreme Court in the Habeas Corpus case was subsequently criticised by many prudent minds on the ground that the courts cannot sanction a practice which was manifestly arbitrary and it cannot put the interests of the oppressive State above the fundamental rights of the individual.

In one of his interviews, late Chief Justice P. N Bhagwati, who was part of the five-judge bench which heard the Habeas Corpus case, expressed his remorse for his majority pronouncement in the ADM Jabalpur case. He said: The Supreme Court’s attitude was far from satisfactory during the Emergency period.

The Supreme Court’s decision to expand its jurisdiction, under Article 142 of the Constitution of India, and an unwavering intention to introduce a new concept of “Judicial Activism” was largely regarded as an exercise undertaken to whitewash the guilt, in the words of late Justice P.N. Bhagwati, perpetrated by the apex court in the ADM Jabalpur’s case. The subsequent pronouncement of the apex court in 1978 in the Maneka Gandhi’s case bears testimony to this very fact.

The procedure established by law was superseded, in the aforementioned case, by the due process of law. Forty-one years later, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud in his Right to Privacy verdict has overruled his father’s decision. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud wrote, “The judgments rendered by all the four judges constituting the majority in ADM Jabalpur are seriously flawed."

"Life and personal liberty are not creations of the Constitution. These rights are recognized by the Constitution as inhering in each individual as an intrinsic and inseparable part of the human element which dwells within," Justice DY Chandrachud wrote in his privacy judgment. The second occasion in which the son has overruled his father’s decision is on the recent verdict pertaining to Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code.

Section 497 which was unanimously struck down by the Supreme Court reads as follows: Adultery.—Whoever has sexual intercourse with a person who is and whom he knows or has reason to believe to be the wife of another man, without the consent or connivance of that man, such sexual intercourse not amounting to the offence of rape, is guilty of the offence of adultery, and shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to five years, or with fine, or with both. In such case the wife shall not be punishable as an abettor. This Thomas Babington Macaulay’s provision was regarded as highly discriminatory as it reduces women to a mere ‘chattel’ status.

When the Section 497 was challenged before the Supreme Court in 1985 a judgment authored by Justice Yeshwant Vishnu Chandrachud, father of Justice D. Y Chandrachud, in Sowmithri Vishnu vs.Union of India had upheld the constitutional validity of the aforementioned section.

The then Chief Justice of India Y V Chandrachud had held that: “It is better, from the point of view of the interests of the society, that at least a limited class of adulterous relationship is punishable by law. Stability of marriages is not an ideal to be scorned”.

Thirty-three years after his father’s pronouncement Justice D.Y.Chandrachud overturned the 1985’s verdict saying the perspective taken in the earlier judgment cannot be regarded as a “correct exposition” of the constitutional provision. Justice Chandrachud held that women have equal rights under the Constitution of India and their independent existence should not be compromised.

It is essential to comprehend the distinction between a civil remedy and a criminal remedy to appreciate the verdict pronounced by the Supreme Court on Adultery. Criminal offence is regarded as an offence against the State and it entails a punitive action against the convict. However, a civil remedy entails either compensation (liquidated or unliquidated) in monetary terms or divorce in marital related affairs.

The Hindu Marriage Act of 1955 contains an explicit provision under Section 13(1) (i) for seeking divorce if adultery could be proved by either spouse and other religions have their own personal laws where adultery is a ground for seeking divorce.

The court has arrived at a conclusion, rather unanimously, that an issue which concerns two individuals should not be regarded as an offence against the society at large.

However, the moral aspect behind the Supreme Court’s latest 497 verdict is occupying much space in the public discourse. One should realise that a constitutional court verifies a specific provision, under challenge, on the cornerstone of whether it is constitutionally tenable or not. The court has no obligation to delve into the moral aspects of a provision.

The Supreme Court’s primary onus is to uphold the constitutional guarantees and to certify as to whether a specific provision of law under contention is in compliance with the constitutional safeguards or not. When the answer is in affirmative such a provision should be allowed to pass the muster of judicial scrutiny and if such answer is in negative then the court possess an inherent right in striking it down.

My moral values unequivocally compel my conscience to endorse father’s standpoint of 1985 on adultery, however, my legal knowledge reminds me that no provision of law which is manifestly arbitrary and which is in categorical contravention of the Part III of the Constitution of India be allowed to sustain.

PVG Umesh Chandra