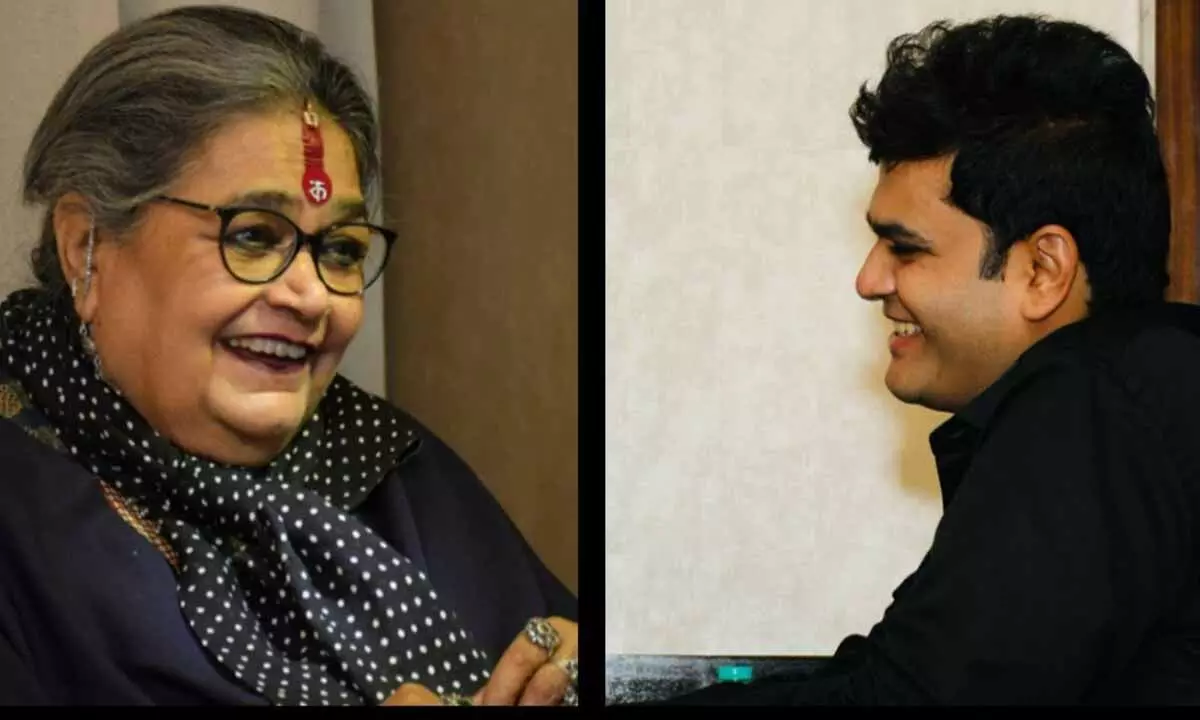

Usha Uthup and Rhythm Wagholikar on Music, Identity, and a Life Sung in Truth

She Owns Her Truth: Usha Uthup in an Exclusive with Rhythm Wagholikar

In the heart of a bustling city, where the cacophony of life often drowns the subtle melodies of the soul, I found myself standing before a door that promised an encounter with another music icon. The door creaked open, revealing a room bathed in warm hues, and there she was—Usha Uthup.

Clad in a vibrant sari that danced with every colour imaginable, her presence was both commanding and comforting. Her signature bindi sat proudly on her forehead, and her bangles chimed softly, echoing the rhythm that has been the heartbeat of her life. Her eyes, lined with kajal and framed by glasses, sparkled with a mischief that seemed eternal and a wisdom that only time could grant.

“Come in, love,” she beckoned, her voice a rich contralto that resonated with warmth. “I’ve been waiting.”

As I stepped in, the room seemed to embrace me, much like the woman who now stood before me—a living testament to the power of authenticity. There was no artifice in her greeting, only a genuine openness, as though the music that had connected her to millions around the world also tethered her to every single person she met.

“Ma’am?” I ventured hesitantly.

She chuckled; a sound as melodious as her songs. “Ma’am? Call me Didi, Rhythm.”

And just like that, the formalities dissolved. She picked up the phone, her voice turning affectionate. “Hi love, this is Usha… Usha Uthup. I need three coffees, one cold chocolate, and some sandwiches to munch on.” Her tone was as familiar as if she were speaking to an old friend, and perhaps, in her world, everyone was.

As we settled in, she leaned back, her demeanor relaxed yet regal, as if every fold of her sari carried with it a piece of musical history. “Let’s keep this extempore,” she said, setting the tone for our conversation—unfiltered, honest, and entirely from the heart.

“I come from a Christian school, a Tamilian home, and was surrounded by Muslim neighbours,” she began, her voice weaving through memories. “That’s what truly made me feel secular.” Her upbringing was a tapestry of cultures, each thread contributing to the rich fabric of her identity. It wasn’t just a story of tolerance—it was one of celebration. She wasn’t shaped by boundaries, but by bridges.

She recalled her school days with a fond smile. “My teacher, Mrs. Davidson, thought my voice had too much depth. She couldn’t place me with the other girls in the choir. So instead, she handed me a trampoline and asked me to join the clappers.” She laughed, not with bitterness, but with the joy of someone who had long since made peace with the past. Who knew the girl who couldn’t sing in the choir would go on to sing for millions?

Usha Uthup never trained in classical music for a long tenure. She didn’t belong to the lineage of gharanas. Her voice didn’t climb the scales with studied precision—it shook them with its soulfulness. Her strength was not in technical finesse, but in emotional resonance. “I never thought of music as a career,” she admitted. “Back then, it wasn’t about breaking stereotypes; it was about embracing who I was. The universe seemed to conspire in my favour.”

There was no rebellion in her voice, only grace. “I’m a people’s person,” she said. “Music isn’t my business; communication is.” That perhaps explained why her songs felt like both performances and conversations. She was never trying to impress; she was simply reaching out.

Fluent in Tamil, English, Hindi, French, and Marathi since childhood, she had an uncanny ability to blur lines. Today, she sings in 17 Indian languages and 8 foreign ones and constantly adding more to her repertoire. She had no training, yet her voice became a bridge across cultures, castes, and countries. “For me, music has no boundaries—no caste, no creed, no colour, no gender. The song is always more important than the singer.”

Her journey began in nightclubs, and even there, she made a difference. “People expected a nightclub singer to wear a long, shimmering gown, maybe show some body. But I walked in with my sari, bindi, and bangles. I was gharelu—homely—and proud of it.” She made the sari just so iconic, made tradition rebellious. In spaces that thrived on artifice, she was honest. In an industry that celebrated the exotic, she brought the comfort of the familiar. The nightclubs then would read Tonight and every night Usha…Usha Uthup, no cover charge.

Her father was a policeman, her mother and grandmother steeped in culture. From them, she inherited discipline and depth. “My limitations became my strengths,” she said. “I didn’t see it as breaking barriers—I was just being me.”

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, the very idea of a sari-clad woman crooning in a nightclub was unthinkable. And yet, there she was, singing “Fever,” “Tom Jones,” “Frank Sinatra,” and even “Skyfall”—her rich, smoky voice pouring from a visage wrapped in tradition. “The voice that emanated from this Indian body,” she said, smiling, “always surprised people.”

But her Indianness was never for show—it was devotion. “It’s fantastic to be a citizen of the world,” she said, “but I always say, ‘Thank you, God, I am Indian.’ And thank you for the sari.” That piece of cloth was more than clothing; it was her identity, her resistance, her pride.

In every performance, she introduced her team—the musicians, the technicians, the people behind the scenes. “For the last 56 years, I’ve done this. They’re my family. How could I not?” In a world that often centers the spotlight on one, she shared it with many.

Her career, spanning more than five decades, is a saga of reinvention. From singing disco hits like “Hari Om Hari” in the 1980s to winning a Filmfare Award for “Darling” in ‘7 Khoon Maaf’, she has been unrelentingly relevant. Her collaborations range from R.D. Burman to Bappi Lahiri, from jazz bands in Kolkata nightclubs to symphonies abroad. She even recorded Adele’s “Skyfall” in her own voice—haunting, regal, unforgettable.

She sang “Darling,” a chartbuster that catapulted her voice into a whole new generation, and yet it was sung with the same ease with which she once sang bhajans at home. That duality—of being rooted and reaching out—is what made her a musical genius.

She reminisced about the greats who shaped her—Harry Belafonte’s “Matilda” was one of her earliest inspirations. Though she never met him, he was in her bones. Then there were other singers she liked —Girija Devi, Kishori Amonkar, RD Burman. “And Lataji…” she whispered, her voice softening. “Lataji Mangeshkar was… pure love.”

Her eyes lit up as she shared a memory. “I performed for her 75th birthday and shouted from the stage, ‘Didi, I need your 2 kg of mishri!’ And would you believe it—she sent it, couriered specially to me.” She laughed, but the tears weren’t far behind. “Whenever I passed by Peddar Road, I’d call her, just to hear her voice. I would always say, ‘, the world needs people like you.’”

The reverence she held for her contemporaries and juniors alike was humbling. “I miss KK so much. Such a beautiful voice, gone too soon. And I always try to call Shankar Mahadevan, Harriharan, Arijit, Shreya… and others, I just want to tell them I’m listening. Their music means something.”

At 77, she isn’t resting on legacy. “I’m learning more Western music—French, Spanish, Italian. I’m trying to find the links between their traditions and ours. Music is a study, an eternal one.”

When I asked her if she had any dreams left, she didn’t hesitate. “There’s nothing specific. But I want to keep giving and loving. If my music gives joy, my job is done.”

And then I asked her a question she said only one other person—her nephew—had ever asked. “What message would you leave the world when you’re gone?”

She paused, took a sip of water, and closed her eyes. “I want to be remembered as someone who brought smiles. Through my music, through the way I spoke, through the way I loved. And above all, I want to take my sari to the world. I take immense pride in it.”

Before I left, she sang. A bhajan in Haryanvi—soulful, resonant, pure. Then a snippet of “ye mat Kaho khuda se,” then something French, Italian, Spanish and many others. In her voice, every language became home. It wasn’t mimicry—it was communion. And with every note, she reminded me that music, at its best, doesn’t just entertain. It heals. It binds. It blesses.

As I stepped away, the echo of her voice lingered. It wasn’t just the music I carried with me—it was her spirit. Her unwavering belief in the power of love, laughter, tradition, and, above all, connection.

Usha Uthup didn’t chase stardom. She simply sang. And in doing so, she became a star the world could never quite look away from. She sang not to dazzle but to embrace. Not to conquer, but to console. In her bangles, her bindis, her saris, and her voice lived a truth so rare it felt like a benediction.

And as the door closed behind me, I realised I had not just met a pop queen. I had met a heartbeat.