Repeal 1987 Act to liberate Hindu faith in Telugu States

The 1987 Act significantly impacted Telugu Brahmanas and Hindu institutions, fostering deep disillusionment with the TDP. Politicians and bureaucrats colluded to exert strict control over temples, enabling mismanagement and misappropriation of temple lands, wealth, and income. Their increasing interference in religious practices undermined temples’ spiritual authenticity, endangering cultural continuity and community cohesion. These changes continue to weaken temples’ financial stability and disrupt traditional rituals

This commercialisation starkly contrasts with other faiths. Muslims enter mosques and Christians attend churches without fees, as these spaces remain free from state control. Yet, the unconstitutional takeover of temples has imposed a financial burden on Hindus, effectively turning spirituality into a transaction. This modern “temple tax” surpasses even Aurangzeb’s infamous Jizya, discouraging poorer Hindus from visiting temples due to costs. The result is a growing disconnection from spiritual roots, fostering cultural deracination

The relationship between Telugu Brahmanas and the Telugu Desam Party (TDP), a major political force in Andhra Pradesh (AP), has been fraught with tension due to conflicting views on historical policies, particularly the AP Charitable and Hindu Religious Institutions and Endowments Act of 1987 (here after the 1987 Act) enacted during Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao’s (NTR) tenure. To understand this dynamic, we must examine the socio-political context, the policies’ implications, their impact on Hindu communities, and propose solutions to address persistent grievances.

Historical context - AP’s socio-political evolution:

AP’s political landscape has been shaped by caste dynamics and ideological differences. Established in 1953 from Telugu-speaking regions of the Madras Presidency and expanded in 1956 with parts of Hyderabad State, the state has been influenced by two prominent land-owning castes: Reddys and Kammas. Historically, both communities were torchbearers of Sanatana Dharma, patronising Brahmanas and Hindu institutions. However, their political trajectories diverged over time.

While the Reddys gravitated toward the Indian National Congress (INC), the Kammas, seeking a counterbalance, aligned with the Justice Party, a Dravidian movement that was critical of Hindu religion and the role of Brahmanas. This ideological influence shaped the perspectives of some Kamma intellectuals and leaders, though many continued to engage with Hindu practices personally. After the 1953 division of the Madras Presidency, the Justice Party’s influence waned in Telugu regions, and the Reddy-dominated Congress gained prominence. Many Kammas turned to entrepreneurship, including the film industry, becoming an economic powerhouse but remaining politically marginalised until the 1980s.

Rise of Telugu Desam Party:

In 1982, the public humiliation of Chief Minister T. Anjaiah, a Reddy, by Rajiv Gandhi during a Hyderabad visit sparked widespread outrage, perceived as an insult to Telugu pride (Atma Gauravam). NTR, a charismatic film star and devout Hindu, founded the TDP, capitalising on this sentiment. In 1983, the TDP won a landslide victory in the AP Assembly elections, ending the dominance of the Congress party.

NTR’s spiritual persona and patronage of Brahmanas initially inspired hope among Telugu Brahmanas, who viewed him as a champion of Hindu traditions. However, policies shaped by a coterie of Kamma intellectuals and bureaucrats, influenced by the Justice Party’s ideology, soon led to friction with the Brahmana community, particularly through the enactment of the 1987 Act.

Challa Kondaiah Commission- A turning point

In 1984, the TDP government established the Hindu Endowment Commission, led by Retired Chief Justice Challa Kondaiah, a Kamma from Anantapur district. Educated in Madras during the peak of the Dravidian movement, Kondaiah’s perspective reflected its ideology. Tasked with reviewing temple and endowment administration, the commission’s 1986 report proposed sweeping changes, culminating in the 1987 Act. While framed as a governance reform, the Act’s provisions were perceived as an assault on Brahmanas and Hindu religious traditions, echoing the Justice Party’s critique of Hindu traditional structures.

The 1987 Act: Key provisions and harms:

The 1987 Act introduced measures that disrupted long-standing temple traditions and marginalised Brahmanas in several ways:

• Section 16 abolished hereditary roles such as trustees, mutawallis, or dharmakartas, changing traditional temple governance structures.

• Section 25 mandated bureaucrats to set schedules of articles and requirements for worship and offerings, undermining priests’ autonomy and subordinating religious practices to state control.

• Section 34 terminated hereditary roles for Archakas, Mirasidars, and other functionaries, stripping them of traditional responsibilities and livelihoods.

• Section 144 abolished priests’ shares in hundi, ritual fees, and income from other services. It also abolished rights to temple lands allocated for their sustenance.

These provisions impoverished Brahmanas, disrupted sacred practices, and subjected temples to bureaucratic control, raising concerns about the erosion of Hindu traditions under the guise of reform.

Undermining of Brahmanas and Hindu institutions:

The 1987 Act significantly impacted Telugu Brahmanas and Hindu institutions, fostering deep disillusionment with the TDP. By eliminating hereditary rights and temple incomes, the Act deprived priests of their traditional livelihoods, leading to financial hardships and a shortage of trained Archakas as many pursued other professions. Politicians and bureaucrats colluded to exert strict control over temples, enabling mismanagement and misappropriation of temple lands, wealth, and income. Their increasing interference in religious practices undermined temples’ spiritual authenticity, endangering cultural continuity and community cohesion. These changes continue to weaken temples’ financial stability and disrupt traditional rituals.

Telugu Brahmanas felt betrayed by the TDP, especially by NTR, whose spiritual persona and support for Hindu traditions had initially inspired expectations of protection for their community and religious roles. Instead, the Act’s reforms economically and socially marginalised Brahmanas, diminishing their livelihoods and roles as spiritual leaders. Although amendments in 1990 and 2017 by Congress-led governments offered some relief, they failed to fully address the Brahmanas’ economic struggles, reduced roles, and exclusion from temple governance. Ongoing political and bureaucratic interference has further eroded their social prestige and the integrity of Hindu institutions, weakening their spiritual authority in Hindu society.

Broader impact on Hindu society:

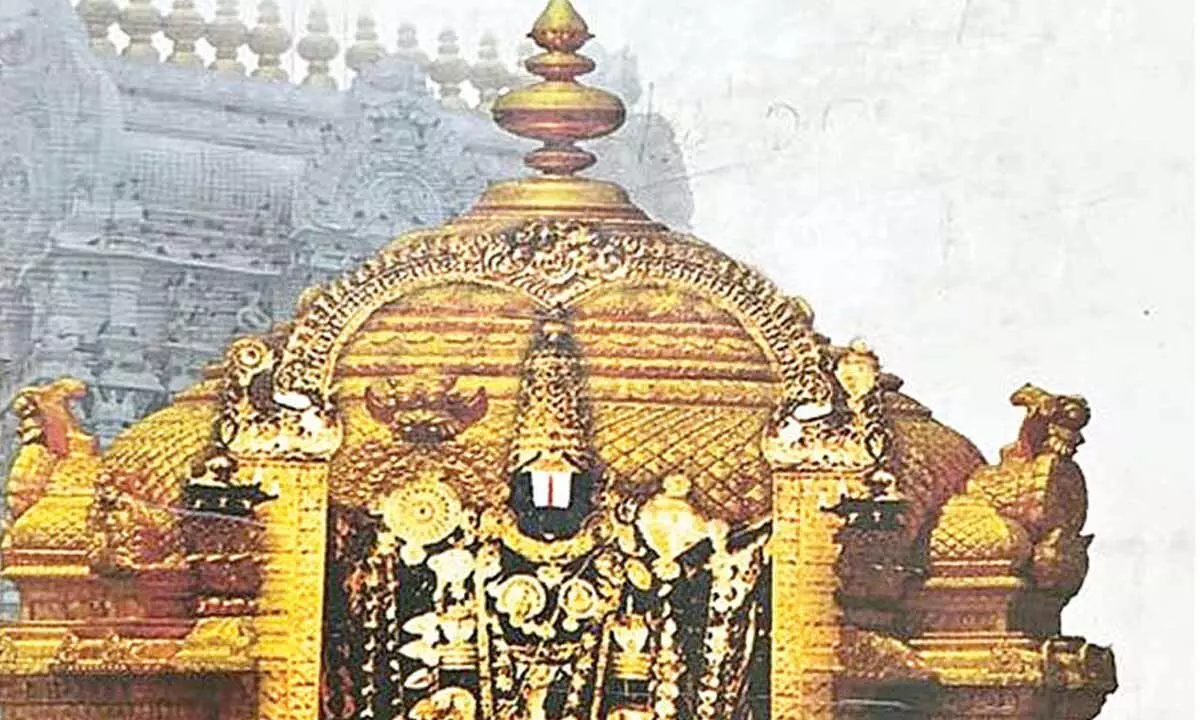

The 1987 Act has profoundly reshaped Telugu Hindu society, undermining the sanctity of temples, which have long served as vibrant hubs of spiritual and cultural life. Under the guise of reform, the Act has turned sacred temples into profit-driven commercial enterprises. From shoe stands to prasadam, darshan to special sevas, every aspect of temple worship is now monetised. Devotees increasingly feel like they’re buying movie tickets rather than seeking divine connection. A fundamental question arises: what right does the government have to charge Hindus for darshan of their own deities?

This commercialisation starkly contrasts with other faiths. Muslims enter mosques and Christians attend churches without fees, as these spaces remain free from state control. Yet, the unconstitutional takeover of temples has imposed a financial burden on Hindus, effectively turning spirituality into a transaction. This modern “temple tax” surpasses even Aurangzeb’s infamous Jizya, discouraging poorer Hindus from visiting temples due to costs.

The result is a growing disconnection from spiritual roots, fostering cultural deracination.

Worse, this environment emboldened Christian missionaries, who exploited the situation by contrasting the paid access to Hindu temples with promises of financial aid and free worship in churches. This predatory tactic has fuelled conversions, luring vulnerable Hindus away from their faith. By taking-over and commercialising temples, the government not only undermines Hindu spirituality but also threatens the cultural fabric of Telugu society, paving the way for Christianisation.

Restoring secularism and Hindu rights:

Secularism, a cornerstone of the Constitution, mandates a clear separation between State and religion. Yet, the State’s control over Hindu temples casts a dark shadow over its commitment to secularism. Articles 25 and 26 enshrine the fundamental rights of all citizens to freely practice their religion and manage religious institutions without State intrusion. By selective control of temples while leaving churches and mosques untouched, the State flouts constitutional equality, denying Hindus equal religious freedoms granted to Muslims and Christians.

To address these grievances and restore secularism, the following steps are essential:

• The 1987 Act must be repealed to eliminate state control over Hindu temples and rectify its detrimental effects on Brahmanas and Hindu society.

• A new legislative framework should establish inclusive temple management through Temple Committees comprising religious figures (Archakas, Pujaris, and Dharmacharyas) and devotee representatives.

• The new Act must explicitly prohibit bureaucratic or political interference in temple affairs, liberating Hindu institutions from state oversight and aligning with the constitutional principle of secularism.

• By restoring the rights of Hindus to manage their religious institutions, the new framework will uphold the fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 25 and 26, ensuring parity with Christians and Muslims.

This approach will restore the sanctity of temples, empower Hindu society, and safeguard Telugu Hindus’ spiritual and cultural heritage.

Conclusion:

The 1987 Act remains a deeply painful chapter for Hindu society and Telugu Brahmanas, who rightly view it as an assault on Hindu traditions. Rooted in the Justice Party’s anti-Hindu and anti-Brahmana legacy, the Act impoverished Brahmanas, subjected temples to bureaucratic and political control, and undermined the Hindu cultural ecosystem. Its lingering effects—pauperisation of Brahmanas, erosion of spiritual traditions, and increased vulnerability of Hindus to Christian missionary activities—continue to weaken Hindu society.

To uphold the constitutional principles of secularism and equality, the 1987 Act must be repealed, and a new Temple Act enacted to liberate Hindu temples from state control.

By empowering religious figures and devotees to manage temples in accordance with their sampradaya, this reform will restore the sanctity of Hindu institutions, protect the fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 25 and 26, and preserve the rich spiritual heritage of Telugu Hindus for future generations. The time has come to act decisively to safeguard Sanatana Dharma.

(The author is a retired IPS officer and former Director of CBI. Views are personal)