Surrender is the only way forward for naxals

Democracy remains the decisive path to change

Even after independence, three major internal challenges have long plagued the nation: Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir, separatist militancy in the Northeast, and the scourge of naxalism. The first two issues have been effectively addressed under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Now, the country is witnessing the final phase of dismantling the third: Left-wing extremism, aka Naxalism.

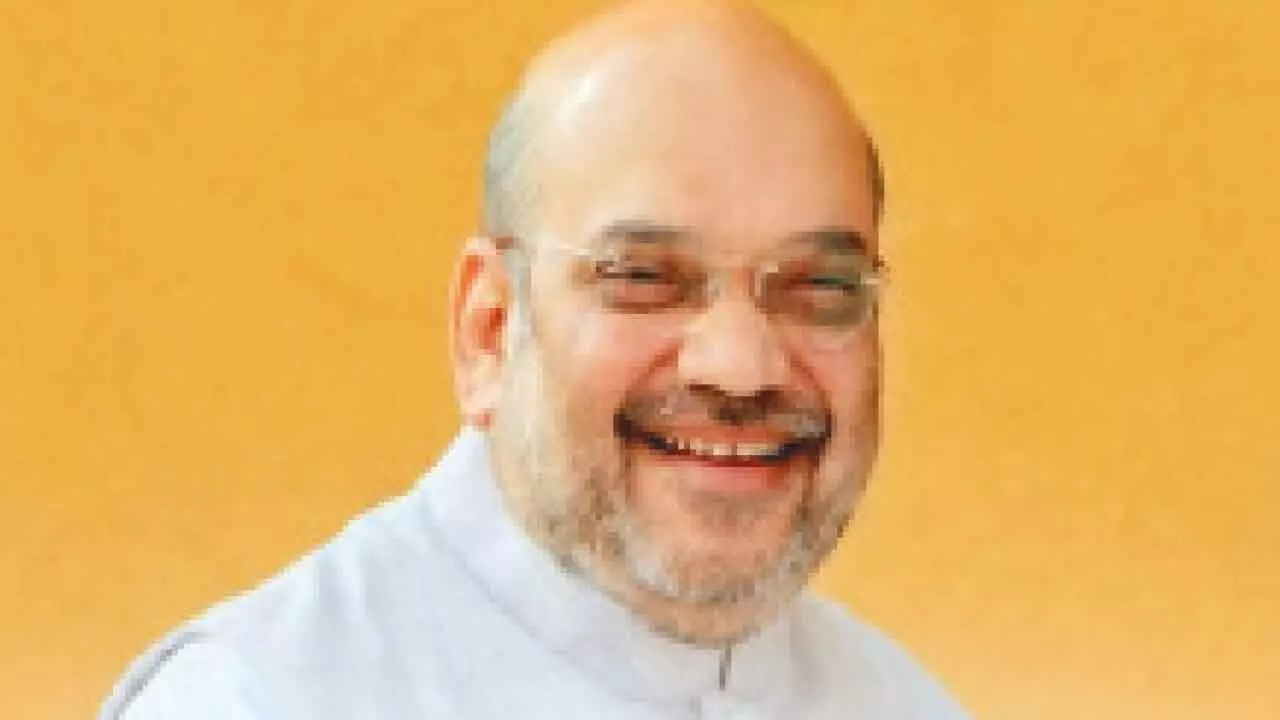

At the recently held “Bharat Manthan” event organised by the Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, Union Home Minister Amit Shah categorically rejected overtures from naxal factions calling for talks and ceasefires. He made it clear that while the government is committed to the Constitution and the rule of law, those who have chosen the path of violence will not be welcomed with open arms by simply declaring their intent to lay down arms.

I had the opportunity to attend this event and offer insights into the social, political, and developmental challenges in Maoist-affected areas. What has brought the nation to this turning point is not just the success of security operations, but a broader national effort encompassing social awareness, developmental initiatives, and democratic empowerment.

In his Independence Day address this year, the Prime Minister spoke with heartfelt concern about how tribal communities have suffered immensely due to naxal violence. Generations of tribal families have lost their youth—bright, promising minds misled into armed struggle. This loss is not just personal but a national tragedy. The government is therefore striving to empower tribal communities, offering educational and developmental support to enable their youth to compete globally and showcase their talents. However, the Maoist leadership continues to obstruct this progress. By hiding behind forests and portraying themselves as protectors of tribals, they seek to maintain their grip through intimidation and misinformation.

The government has consistently offered naxals a chance to participate in the democratic process. However, rather than engage constructively, they have aligned with anti-national forces and sought weapons from external sources. This betrayal of the democratic spirit has left the government with no option but to act decisively.

Several factions within the Maoist movement remain at odds with one another, yet their capacity for disruption remains a shared threat. Some claim to have laid down arms and call for dialogue, while others have rejected even that. But the Centre maintains a firm and unified position: the time for negotiations has passed. Surrender is not a matter of public declaration—it is a responsibility. The only path remaining is to join the democratic mainstream and work the constitutional framework.

The perception of naxalites has undergone a dramatic transformation in public opinion. Once seen by some as revolutionaries, they are now widely regarded as domestic threats. This change did not happen overnight. It is the outcome of years of brutal killings, often targeting the very people they claim to protect.

Their acts of violence against police, elected leaders, and especially tribal villagers accused of being “informants” have eroded any residual sympathy. In the last two decades (2005-2025), an estimated 10,500 to 12,000 people have lost their lives to naxal-related violence. Of these, around 3,500 to 4,000 were civilians, and approximately 2,500 to 3,000 were personnel from the police and central security wings. The rest belonged to the Naxal cadre.

Most of the civilians killed were tribal villagers, targeted under suspicion of collaboration with authorities. In Chhattisgarh alone, official records show that police registered over 2,000 such cases in the past 20 to 25 years. In August 2024, for instance, the brutal murder of Nilso alias Banti Radha in Khammam district’s Charl mandal caused widespread outrage among Dalit and tribal communities. Once a committed Maoist, she was executed by her own organisation. Her death exposed deep fissures within the Maoist ranks—ranging from forced recruitment and internal violence to systemic abuse of cadres seeking a return to normal life.

Between 2001 and 2024, naxals killed at least 1,623 tribals in the Bastar region alone. In 2020, Bijapur district recorded 25 such murders. These so-called “people’s courts” are nothing more than instruments of fear, designed to terrorise villagers and deter any cooperation with development initiatives.

It is precisely this legacy of violence that prompted Prime Minister Modi to highlight the issue during his Independence Day speech. Bastar, once a region associated with landmines and gunfire, is now making headlines for its youth taking part in sports and national development. The Maoists’ record is further tarnished by evidence of cooperation with terrorist organisations.

In 2005, bullets used by Naxals were traced to Pakistan—the same type used in the Parliament attack.

In 2008, it was discovered that over 500 from the Maoist cadre in Kerala had trained with members of the banned Islamist group SIMI. Subsequent arrests revealed efforts to establish joint operations with groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba and Pakistan’s ISI. Arms trafficking routes from Nepal and suspected Chinese intermediaries added another layer of international conspiracy.

Maoists also formed tactical alliances with northeastern insurgent groups like NSCN-IM and PLA, while maintaining ideological solidarity with extremists in Jammu & Kashmir and Maoist groups in Bangladesh and Nepal.

As these revelations reached the public, support for the movement dwindled. Even within tribal communities, Maoist recruits have sharply declined. Lower-level cadre are either intimidated or ideologically disillusioned. Urban sympathisers, once vocal, now privately admit that violent insurgency has achieved little and that democratic engagement is the only viable path forward.

Notably, some senior Maoist leaders have already recognised this reality. Sujatakka, alias Pothul Kalpana, one of the most prominent Maoist figures, carrying a reward of Rs one crore on her head, surrendered recently. She was facing over 100 criminal cases. Her decision to give up arms and rejoin society marks a symbolic shift. The police facilitated her reintegration with immediate financial support and security. Her surrender has already inspired others within the movement to contemplate a similar step. In today’s technologically advanced world, the space for armed rebellion has shrunk rapidly. Intelligence capabilities and ground-level operations have become far more effective. Hiding in forests is no longer a sustainable option. The movement’s remaining leaders must now make a choice: cling to a crumbling ideology or re-enter society with dignity through surrender and rehabilitation.

If others follow Sujatakka’s example, the cycle of violence and counter-violence can end. It will allow the state to focus fully on external threats without the burden of internal subversion. Eradicating naxalism is akin to curing a disease from within—it strengthens the nation and fortifies its democratic foundation. The central government is unequivocal in its approach. Talks and ceasefires are not on the table. The only way forward for them is surrender, rehabilitation, and full integration into democratic life. It is time for those still in the jungles to accept this truth and take responsibility—for themselves, for their communities, and for the nation.

(The writer is a BJP National Council member)