Use of religion as a key factor in development

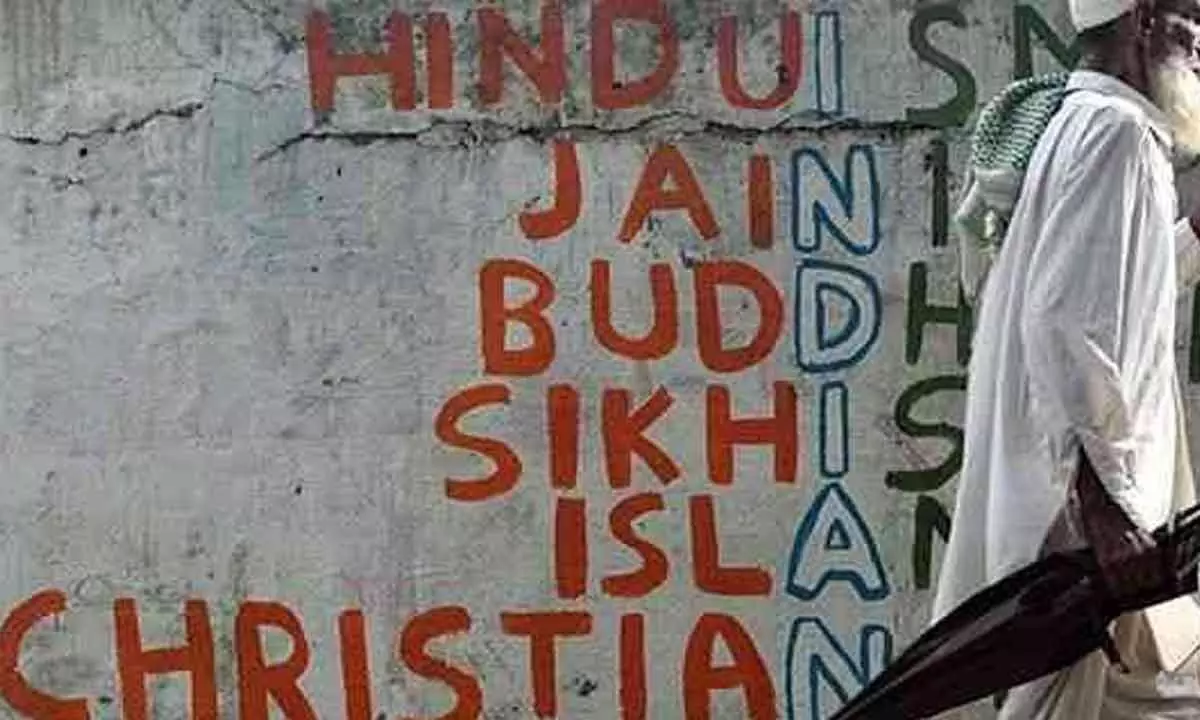

Faith-based development is fine, but guard against conversion of one’s faith

Can religion be the key to development in the world? Can development be planned through religion? Do development studies encompass religion to evolve ways and means of modernising a society? The debate in the West still continues on the efficacy of religion as a key contributor in the development of a region.

Gilles Carbonnier is the vice-president of the International Committee of the Red Cross and Professor of Development Economics at Geneva's Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies. Carbonnier is an academic, development economist and passionate humanitarian. He has traced the early theories of development (in the West) to enlightenment and modernisation traditions. But, development studies have widely neglected religion, he feels.

In one of his works on religion and development, he says "given that the origins of development assistance trace back to missionary ventures and religiously inspired initiatives during the colonial era, this is something of a surprise. Today, faith-based organisations remain highly prominent actors in the aid industry. (…) The lack of attention to religion and faith in development research and policy thus stands in stark contrast to the paramount role played by religion in the daily lives of individuals and communities, particularly in the most active field of international development cooperation, the developing world."

For those who believe in the role of religion in development, it was wrong to separate the functions of the State and the Church. However, even if the West agreed to separate the Church from the governance, it always used religion to "develop" the backward or uncivilised world everywhere. The name given to this mode of development which always had strings attached to it was aiding faith-based organisations (?).

Thus, we have a Christian organisation, World Vision International, for instance, with the largest budget among humanitarian and development aid non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with total expenditures on international programmes, international relief and rehabilitation programmes, community education and advocacy, administration and fundraising reaching $2.72 billion in 2011 itself. Similarly, the London-based NGO Islamic Relief has grown tremendously "influencing" a large part of the world with its aid activity. It has millions of pounds at its disposal for the "work."

The Indian government is, however, trying to keep a tab on the activities of such organisations now after coming across reports of "misuse" of funds. Several complaints have been received that the organisations have been funding the needy, no doubt, but with an ulterior motive of converting the locals here into their faith. There could be criticism against the Indian government for getting suspicious of the activities of the NGOs, but not only these NGOs are receiving overseas funds but they are not being transparent in showing the records. World over, anyway, there is no doubt as to how the money is being spent and to what end. Faith-related funding is seeking to increase the "size of the faith" everywhere through its "good work."

Giles also refers to the World Bank which engaged with religion and faith-based organisations under President James Wolfensohn in the 1990s. However, all these arguments, in the West, took a blow following 9/11. Governments started studying religious fundamentalism and their own practice of funding through religion.

A few bilateral development agencies, such as the UK Religions and Research Programme Consortium, the Dutch Religion and Development Knowledge Centre, and the Swiss reflection on the Role and Significance of Religion and Spirituality in Development, began to support research into the religion-development nexus.

Secular governments and faith-based organisations can't be compatible with religious extremism taking over the emotions of people. Developmental studies need to incorporate these two into their gamut more and more for a better worldview and safety, too. A serious investigation is needed world over into the faith-based funding of developmental activity.

If India resorts to it or at least keeps a check on it, there should be no complaint against the same. Many governments have started it already.

All this may sound interesting to the Western thinkers and philosophers. But India is not new to this thinking. A proper and unbiased study of Indian history tells us that Indians are not strangers to the religion-development theory. The Indian past tells us that Hindu temples served as nuclei of important social, economic, artistic and intellectual functions in ancient and medieval India. Burton Stein, a historian amongst anthropologists, states that South Indian temples managed regional development functions, such as irrigation projects, land reclamation, post-disaster relief and recovery too.

The place of temples in Indian society is indeed pre-eminent. It played an important role in uniting people through the various ritual activities. All the social activities of villages in medieval south India centered around temples. Temples were the repositories of our tradition, centres of education, charitable institutions, hospitals, centres of preservation of the fine arts and historical records, governing body of local self-government, place of entertainment, meeting place and place of Justice.

Schools and hospitals were often located in the temple precincts, and it also served often as the town hall, where people assembled to consider local affairs or to hear the expression of sacred literature. Only there was no attempt to convert anyone into the local's faith in India in the past. The society had always been tolerant and allowed all faiths to nestle in India and flourish throughout. The aberrations are from elsewhere.

Development was possible in India in the past because a temple was not just a matter of faith or 'Astha.' It was a centre for local administration in whose matters faith had a limited or nil role. A temple was an expression of faith but not the whole faith itself. This is the essence of Hindu life. Rather it was!

One should not forget that religious adherence is on the rise, as is clearly seen in recent research on religious demographics. It plays both negative and positive roles in relation to inclusive growth some might argue. On the one hand, religion-related hostilities, prejudices and biases can lock people out and inhibit inclusive growth.

Beyond poverty alleviation, research also shows that when freedom of religion or belief (including interfaith and intercultural understanding) accompanies the rise of faith, the peaceful conditions necessary for inclusive growth are often strengthened. This has been acknowledged by the World Economic Forum, too.

The faith factor in inclusive growth (or development) is a complex topic which is only just beginning to be analysed. An economy that excludes kills! There should be no doubt about this cardinal principle.

A society that neglects development or the one which focuses only on faith loses out. People at the margins know how to fish, but they don't have access to the pond. They aren't able to engage and participate in the economic systems, markets, relationships, networks of support and collaboration and cooperation, tools, and models many of us take for granted. Hence, focus must be more on an inclusive system. India could become an economy of $5 trillion or even $50 trillion if it includes its population at the margins too. Is it prepared to do so? Or is it only interested in my faith vs your faith challenge?