New education policy: Critical issues

While there is truth in all these points, what does not receive enough attention, is the woefully poor state of institutional capacity, especially at the lower levels of administration.

Failure of education policy has been attributed, at least in part, to implementation issues. In this article, Kiran Bhatty, Senior Fellow at the Center for Policy Research, contends that the poor state of institutional capacity in education, especially at the lower levels of administration, does not receive sufficient attention. The New Education Policy should include a plan for institutional reforms as these are critical for successful implementation of policies and programmes

Failure of education policy has been attributed, at least in part, to implementation issues. In this article, Kiran Bhatty, Senior Fellow at the Center for Policy Research, contends that the poor state of institutional capacity in education, especially at the lower levels of administration, does not receive sufficient attention. The New Education Policy should include a plan for institutional reforms as these are critical for successful implementation of policies and programmes

Failure of education policy has been attributed, at least in part, to ‘implementation’ issues referring broadly to infirmities in institutional design. Poor incentive structures, lack of accountability, inappropriate fund flows, patron-client relationships and rent-seeking opportunities are commonly cited as the bottlenecks preventing policy from having the desired impact.

While there is truth in all these points, what does not receive enough attention, is the woefully poor state of institutional capacity, especially at the lower levels of administration. This is the segment of the administration or implementation machinery that has to deal with the huge surge in demand, and increasingly complex social classroom situations and institutional arrangements.

Unfortunately systematic research on institutions and detailed ethnographic studies of the bureaucracy do not exist. In the absence of quantifiable data, one is constrained to rely on field observations and anecdotal evidence, which tend to be given less attention than they should be, even though they highlight failures in the governance architecture that have an impact on all aspects of implementation.

In fact the absence of data on institutional functioning, despite the huge amounts of data being generated on education in general, is an important part of the problem we face in combating implementation failures. Other aspects of institutional design that need urgent attention are discussed below. As these are critical to the implementation of policies and programmes in education, policymakers would do well to address them on a priority basis.

Architecture, resources for RTE

The Right to Education Act (RTE) makes elementary education a fundamental right, but neither the finances nor the institutional architecture exists to enforce it. In fact there is no estimate of what it will cost to enforce the RTE (even in its most limited interpretation), as none of the states have made that calculation. In fact, it is not even clear how the obligation is distributed between the Central and State governments.

There is no information on the system by which the distribution of finances is aligned to the various objectives of education or levels of government. For instance, will the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) – Government of India’s flagship programme to achieve universal elementary education - provide funds for infrastructure while the states provide for ‘quality’ inputs such as teacher education or academic support, or vice versa? This has become even more pertinent with the devolution of more resources in favour of states, as per the recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission.

There is a legal obligation on the State to provide elementary education equally to all children, but there exist a range of providers, including public, private and public-private partnerships (PPPs). We do not know if the structure of statutory obligations applies uniformly to all of them, or what the interface between different institutional arrangements is, or how these will translate the Right into reality.

Nodal officers for RTE have not been provided yet in every State – some States such as Haryana have an RTE officer at the State level, and some states like Rajasthan have appointed an ‘RTE-in-charge’ at the district level. But many States have none. The Panchayat structures that have been designated ‘local authorities’ in State rules have been given no money, no training and no links to authority - rendering them ineffectual. No grievance redress mechanism exists for citizens, in case of violation of RTE.

The monitoring function has been shifted to the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR), with an annual budget that amounts to Rs 50 per school per year. No mechanisms exist for convergence with the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) or State education departments to link monitoring to feedback. To do justice to the constitutional imperative, appropriate governance architecture and commensurate resources are a necessary condition and should be at the forefront of the New Education Policy (NEP).

Coherence of arrangements

Lack of autonomy, and agency of frontline officials, distribution of resources commensurate with responsibilities, effective authority structures, and basic infrastructural and support systems are other aspects of institutional design that have been off the policy radar with obvious implications on implementation. Some examples to illustrate the failures in these areas are given below,

Cluster resource persons1 are expected to provide academic support, but have no say in training of teachers or authority over them. Similarly, Block Education Officers (BEOs) are expected to monitor schools, without transport, computers or adequate support staff. Block resource persons, who are better resourced, are reduced to conduits for data and information, rather than academic supervision or support.

An increasing amount of time of District Education Officers (DEOs) is spent in court, handling an ever-increasing number of cases filed by teachers and others in the system2. There are no legal officers or conflict resolution mechanisms within the system to ease the situation and allow the DEOs to perform their primary duties.

There are School Management Committees (SMCs)3 for making school development plans, but no system of integrating school plans with state plans. Eventually district and state plans are made on the basis of information in District Information System for Education (DISE) and allocation of resources by the Central Project Approval Board at MHRD, done in an arbitrary fashion at the state and district levels.

There is an elaborate architecture for monitoring, but no mechanisms for feedback, review and action. Monthly review meetings that are held at block and district levels never refer to the information collected in monitoring formats – the agendas are focused on fund utilisation and routine administrative matters.

Teachers for teaching

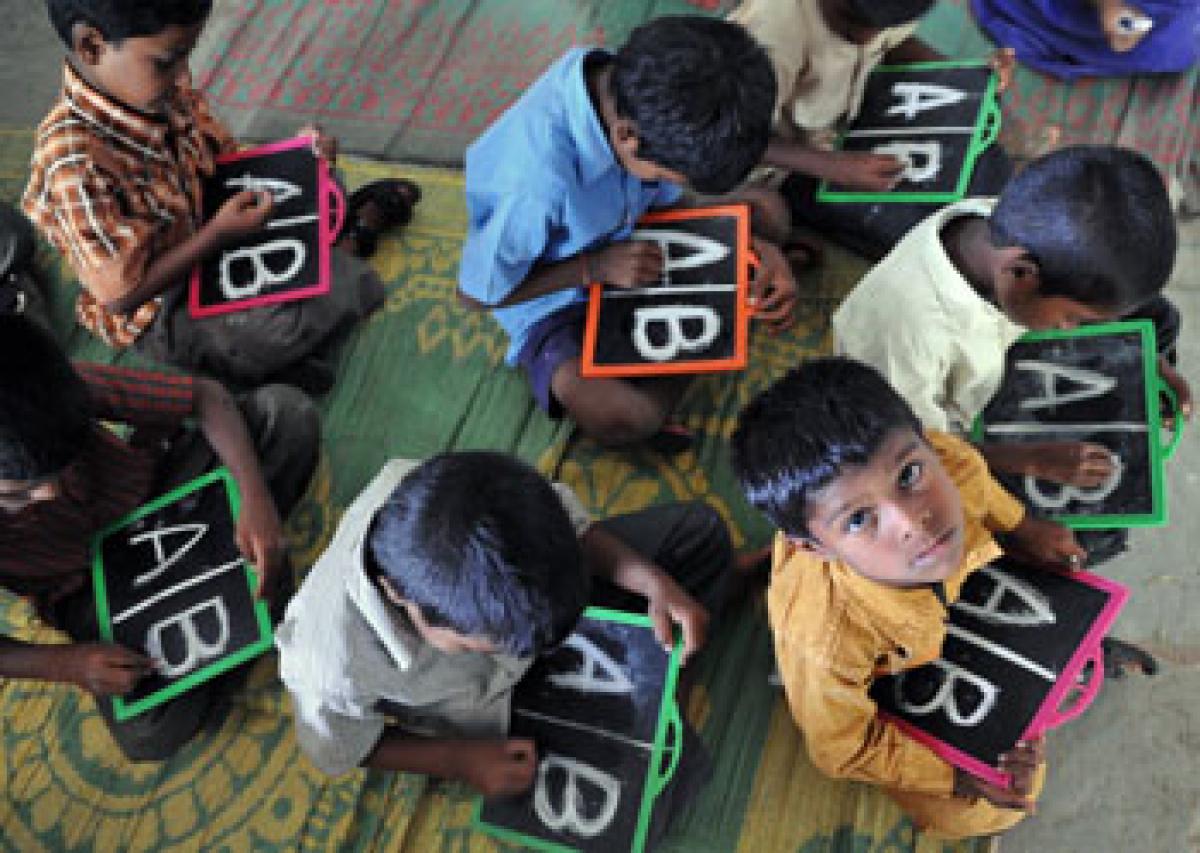

Teachers, being crucial to the delivery mechanism in education, are widely acknowledged as the pivot of failure, especially as far as learning outcomes are concerned. However, much less attention is paid to the institutional arrangements that govern their functioning in the classrooms they are placed in.

For instance, classrooms in government schools have children with little or no support from home, but teachers are given no training to deal with this reality. The increasingly diverse and complex nature of classrooms requires special training for teachers as well as continuous hand-holding of children – both of which currently do not exist.

Further, there are huge teacher shortages (Rajasthan has close to 20% single-teacher schools); despite this, teachers have to undertake a long list of non-teaching tasks as part of their jobs as government servants, alongside teaching responsibilities. These non-teaching tasks include data collection, management of mid-day meals, organising construction work in the school and so on.

During elections, government schoolteachers are posted as booth-level officers on voting days, and they have to prepare, check and maintain electoral rolls prior to voting. The implications for political patronage and misuse of power, besides the distraction from core responsibilities of teaching, could not be more obvious. There is no solution in sight and no will in government to alter this situation.

Teacher recruitment policies defy rationality, having no links between qualifications, salaries and scope of work. They lack autonomy and are at the receiving end of a long chain of authority structures, and yet expected to perform nothing short of wonders in the classroom.

Institutional reforms

The first National Education Policy of 1968 was criticised for not having a programme for action. The second policy of 1986 included a plan of action, albeit added in 1992. A third Education Policy is being framed after a gap of nearly 30 years.

It is now widely acknowledged that governance, which is rooted in institutions, is the key to the success of any policy. The drafters of the new policy would do well to include a plan for institutional reform in their policy framework. (Courtesy: IdeasforIndia; http://www.ideasforindia.in/article.aspx?article_id=1560)

By Kiran Bhatty