Live

- Taluk Guarantee panel

- Uber Launches Uber Moto Women for Safer and Flexible Rides in Bengaluru

- ‘Fear’ pre-release event creates waves

- Champions Trophy 2025 Host Change? Indian Broadcaster's Promo Sparks Controversy

- Nabha Natesh introduced as Sundara Valli from ‘Swayambhu’

- Aamir Khan praises Upendra's ‘UI: The Movie’ ahead of its release

- Celebrations: Keerthy Suresh ties the knot with Antony Thattil

- Indian scientists develop flexible near-infrared devices for wearable sensors

- Wordle Answer and Hints for Today (December 12, 2024) – Solve Wordle #1272

- Kiara blazing through fashion and film

Just In

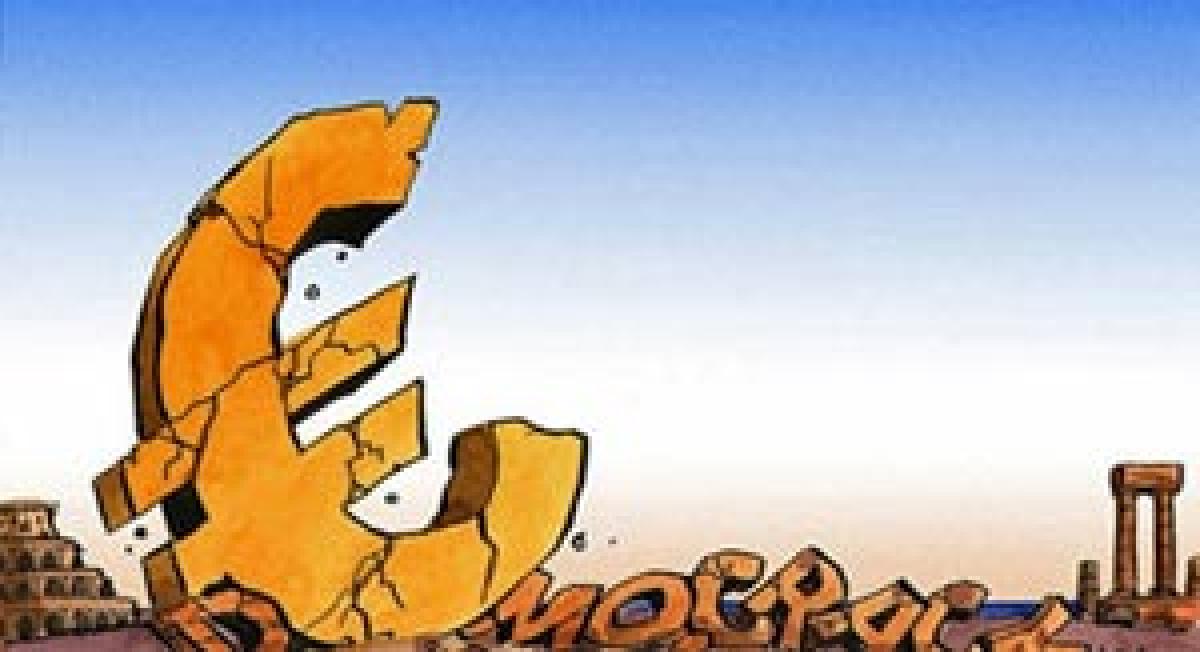

Britain\'s shock vote to leave the European Union - the first time a member-state has chosen to pull out - sends the post-World War Two unification process that has underpinned peace and prosperity on the continent into reverse.

Brussels: Britain's shock vote to leave the European Union the first time a member-state has chosen to pull out sends the post World War Two unification process that has underpinned peace and prosperity on the continent into reverse.

The loss of Europe's second biggest economy and one of its two main military powers triggered a scramble to shore up the remaining 27-nation bloc, amid a rising tide of eurosceptic populism, rather than any radical move towards closer union.

Britain's vote plunges the EU into its third major crisis of the decade after the euro zone debt turmoil that began in Greece and last year's influx of a million migrants and refugees.

British exit negotiations could be long and divisive, with Germany and northern allies keen to keep London as close as possible to the EU market while others, notably France, may seek a tough line to discourage further fragmentation.

So the priority for the governments and institutions at the heart of the EU will be to negotiate a smooth divorce and prevent contagion."Europe will continue but it must react and rediscover the confidence of its peoples," French Foreign Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault tweeted in a first reaction. "It's urgent."

Anti-EU nationalists around Europe, energised by the British Leave campaign that took on and defeated the political and business establishment, are already demanding their own referendums on EU membership or on whether to abandon the euro.

Calls for the European Union to do less, and to focus on essentials, have already begun. But there is little agreement on what those essentials should be. Since its inception, and especially since France rejected a European defence community in 1954, European unity has been a political project promoted through economic interdependence.

"Europe advances in disguise," Jacques Delors, the architect of the EU's single market and common currency, famously said. Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy said the EU should be reformed to concentrate on the economy. Others in France and Germany want to see it do more to control Europe's external borders and manage migration to address citizens' concerns.

Yet migration policy is deeply divisive. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who defied Brussels by shutting out migrants, plans a referendum in October to reject EU policy of sharing out quotas of asylum seekers stranded in Greece and Italy.

EU leaders set out to rebut such notions. European Council President Donald Tusk, the man who chairs the bloc's summits, declared: "On behalf of the 27 leaders I can say that we are determined to keep our unity as 27." Quoting the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, he added: "What doesn't kill you makes you stronger."

With Britain gone, Berlin faces a much more difficult life as the bloc's reluctant hegemon, with an economically weak French partner and a group of southern countries that want it to underwrite their debts and their banks' deposits.

Britain has been the strongest supporter of a free trade and investment partnership under negotiation with the United States, which could become a collateral casualty of Brexit, given public opposition in Germany and Austria as well as France. The eight other countries outside the euro zone - including Sweden, Denmark and Poland - have lost their strongest ally in London and will be a weaker minority in the EU.

"Brexit will oblige some countries to take a decision. They can't stay one foot in and one foot out," former Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta told Reuters, citing the four central European countries that form the so-called Visegrad group, as well as Denmark and Sweden.

Letta said the 19-nation euro zone must move forward as the core of "ever closer union". That vision sends a chill through Warsaw and Prague. For now, differences between Germany and France, which both hold elections next year, are too wide to permit an early initiative to deepen the monetary union.

By Paul Taylor

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com