A salute to two apostles of peace

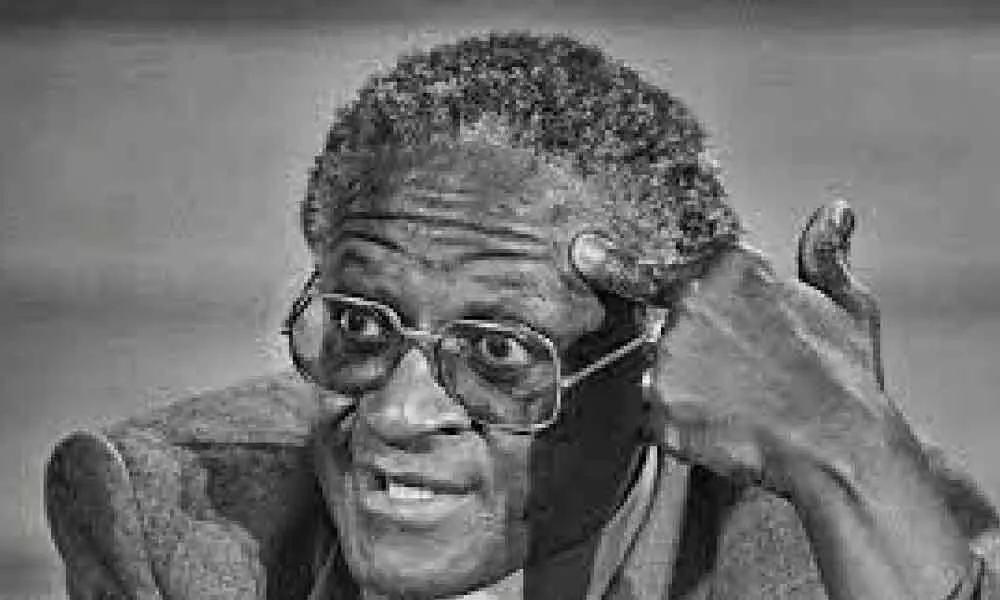

Archbishop Tutu

‘Religious politics’ has been the subject of a high-decibel debate from time immemorial in the country. A hardcore section of nationalists is very happy with the way spiritual figureheads are partnering with politicians to cash in on the historical hostility they carry against a particular minority community.

'Religious politics' has been the subject of a high-decibel debate from time immemorial in the country. A hardcore section of nationalists is very happy with the way spiritual figureheads are partnering with politicians to cash in on the historical hostility they carry against a particular minority community. In a parallel category is another section of self-styled 'progressive minds' that detests involvement of priests, mahants, babas, swamijis in running the governments as extra-constitutional authorities because religion is best beyond the political mainstream. Whom should we support?

Even as the world is reeling under the impact of Covid-19, two influential spiritual icons, a bishop and a monk, left the mortal world within a month of each other. Each leaves behind legacies that will remain relevant for eons. As genuine symbols of humanity, peace and compassion, the two nonagenarians lived by example and showed mankind the positive impact that religious leaders can create to shed hatred for one another, reduce suffering, share love and spread peace.

Acclaimed Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, passed away on January 22 at the age of 96 while Desmond M Tutu, a South African Anglican Bishop, left the world a day after last year's Christmas, aged 90. Their deaths are a great loss for humanity that is struggling to cope with blind faiths, religion-driven bloodsheds and fatalistic symbiotic relation between religious heads and treacherous political class.

Mindfulness and deep listening

Nhat Hanh became a monk at the age of 16 and taught Buddhism at Columbia and Princeton universities from 1961 to 1963 before returning to war-ravaged Vietnam. The School of Youth and Social Service with more than 10,000 volunteers and social workers provided succour to war-affected villages, rebuilt schools and provided medical facilities. Both North and South Vietnam governments treated the US returned peace-lover as an enemy.

As a young monk, he toured the world in 1966 seeking his country's peace much to the chagrin of the regime in Saigon, which excommunicated him. After spending 39 years in exile, Nhat Hanh visited his motherland in 2005. In response to a letter written by the monk on June 1, 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. met him in 1966.

King not only extended his support to the Vietnamese cause but also nominated him for the Nobel Peace prize in 1967. Nhat Hanh settled in Southwest France after he led a Buddhist peace delegation to Paris. In the meanwhile, he developed the Plum Village Buddhist monastery in France into Europe's largest. Later he and his disciples established eight other branches stretching from Mississippi to Thailand.

A master of six languages, he authored more than 100 books and his works have been translated into more than 30 languages. A brain-stroke paralysed Nhat Hanh in 2014 and he returned to a temple in Vietnam where his journey as a monk had begun. He breathed his last in the same temple.

Nhat Hanh simplified religious practise by exhorting the world that every human being can become a Bodhisattva (enlightened) with practice.

He called upon people to find happiness while 'mindfully' attending to everyday chores like sipping tea, doing the dishes and pealing an orange. Going further, he introduced the concept of 'mindful' meditation while walking. His 'mindfulness' has been hailed by Google and globally iconic CEOs, who inculcated the same to improve the focus levels of their employees. The essence of the concept is- Don't be neither future-focussed nor past-obsessed.

Nhat Hanh's concept of mindfulness is close to the extremely popular verse (chapter 2, verse 47) of Bhagvad Gita: karmany-evādhikāras te mā phaleshu kadāchana- mā karma-phala-hetur bhūr mā te sango 'stvakarmanji.

True to the verse's clarion call that "you have a right to perform your prescribed duties, but you are not entitled to the fruits of your actions. Never consider yourself to be the cause of the results of your activities, nor be attached to inaction", the monk called upon people to live in the moment.

In an interview to Oprah Winfrey a decade ago, the monk insisted on relieving the suffering of other person with love and compassion. "Practice deep and compassionate listening. This will help one learn so much about their individual perceptions. That is the best way and the only way to remove maladies like terrorism," he observed. He further said: "Without community we can't go forward. Building the beloved community is important."

Nhat Hanh, who established 10 global practice centres in his lifetime, apart from 1,000 global communities and innumerable online community groups, was eligible for the Noble Peace Prize. According to an estimate, more than 500 monks and nuns ordained in his Plum Village tradition have emerged as powerful torch-bearers, who will continue to spread his message.

A cleric's fight against apartheid

Archbishop Tutu on the other hand used his pulpit to dismantle the heinous practice of apartheid in South Africa. He joined hands with the African National Congress (ANC) when its leader Nelson Mandela was jailed. Being the leader of the South African Council of Churches and later as Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, Tutu always stood by the oppressed classes. He had first-hand knowledge of the ghastly face of apartheid as the head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He played a pivotal role in establishing a new relationship between white and black citizens for which he won Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

Even as the mission was accomplished with the anointment of Mandela as the president of the country in 1994, Tutu sided with people. He decried the policies of Mandela's successors, Thabo Mbeki and Jacob G. Zuma. He went to the extent of castigating the policies in 2011, with "This government, our government, is worse than the apartheid government."

Tutu's most globally famed speech, which has inspired subsequent leaders of mass movements has been- "We had the land, and they had the Bible. Then they said, 'Let us pray,' and we closed our eyes. When we opened them again, they had the land and we had the Bible. Maybe we got the better end of the deal."

A powerful orator, Tutu studied at St. Peter's Theological College in Johannesburg and was ordained an Anglican priest at St. Mary's Cathedral in December 1961. Like Nhat Hanh's, Tutu too authored many books, including "God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time" (2004) and "Made for Goodness" (2010). True to the essence of his 1999 book titled "No Future Without Forgiveness," Tutu always argued in favour of forgiving enemies. Owing to ill-health, he officially retired in 2010.

PACE: Key lessons from the duo

Thich and Tutu left many lessons for humanity. They demonstrated about how one create peace by using religion as a fulcrum irrespective of the government of the day. Thich had to deal with radical Communist regimes, while Tutu witnessed the most ruthless phase of racism. There are four key takeaways from the lives of these two world-renowned impactful spiritual leaders.

Pacifism: No individual and no religious leader can ignore sufferings of fellow-beings, created by barbaric rulers. The two spiritual heads scrupulously followed the principle of pacifism to ensure peace for their citizens. Here is a great lesson for Indian religious heads, who often spread hatred and stoke violence.

Altruism: The duo lived by this concept against all odds. Altruists to the hilt, they worked like activists in a bid to alleviate sufferings of their people. They succeeded in convincing the world that there is no harm in becoming peace mission activists. They exhibited the highest levels of moral standards and gumption to be active in countering the brutality used by the powerful against the powerless. The Gandhian path of non-violence they adopted amidst chaotic phases remains as inspirational.

Community: The two stood for the oneness of the community. Given the comforts provided by their religious positions and the mass following they had, they could have enjoyed a life of bliss, but they chose to be with the community. Their every action was aimed at ensuring peace and joy of the community.

Here lies a big lesson for our intellectuals, academicians and other professionals who prefer to confine to their jobs and activities. Mind you, we are safe when the community is safe. You may be timid, or you may have limitations, but at least you muster guts to lend voice to the people out there in their fight against religious fundamentalism and corrupt governance.

Engagement: Notwithstanding the tyranny of rulers and criticism from opponents, the two did not stop engaging with governments with a positive bent of mind. They earned the confidence of the people and governments by way of unhindered engagement. The beauty of the engagement lies in the opportunity it provides to rectify the faults committed by warring factions while showing commitment for the common good.

One can draw inspiration from the PACE (Pacifism, Altruism, Community, Engagement) mantra of the two noble departed souls to make the world the best place live.

(The author, a PhD in Communication and Journalism, is a senior journalist, journalism educator and communication consultant)

(The opinions expressed in this column are that of the writer. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of The Hans India)