Live

- Workshop conducted on Mathematics

- Revanth visits SLBC tunnel collapse site

- BJP has no discipline within party

- Hyd Muslims erupt in joy to welcome month of Ramzan

- Blue Ghost Touches Down! US firm Firefly makes its first moon landing

- MIMS hosts seminar on new developments in anesthesia

- Shankaracharya sees spiritual renaissance among India’s youth

- CM hits out at Kishan for delay in TG projects

- Accelerate project works: Subbarao

- Rushikonda Beach stripped of its Blue Flag certification temporarily

Just In

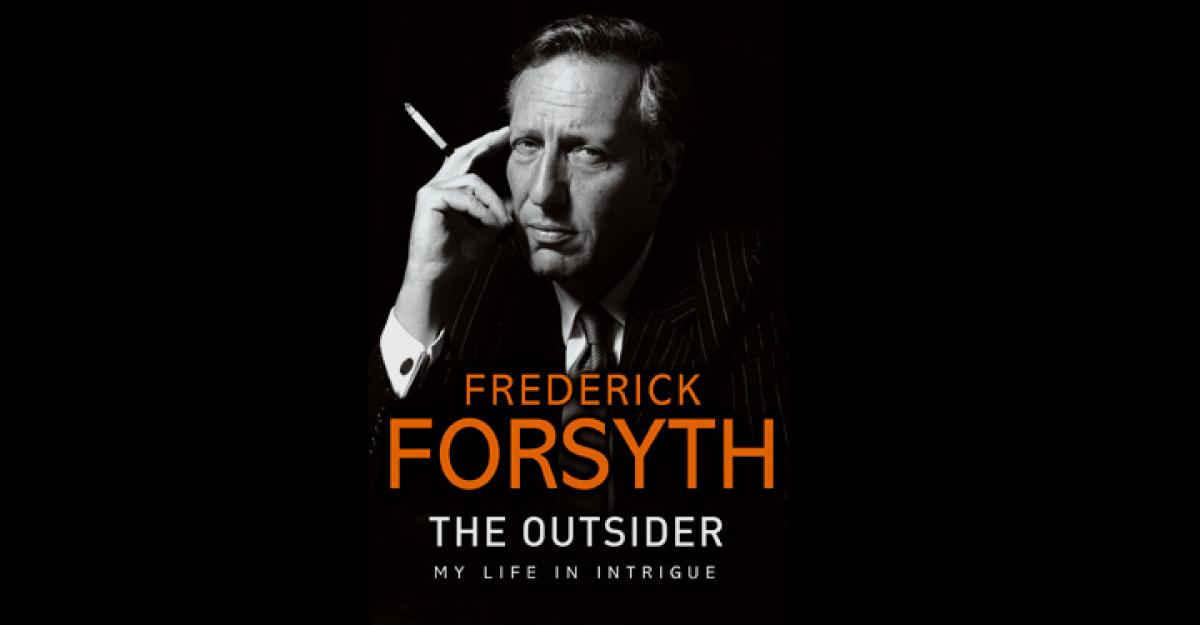

For years, he has regaled us with thrilling tales of plotting (and foiling) high-profile assassinations, unearthing Nazi war criminals, organising coups in Africa, kidnapping sons of US presidents, spy agencies.

For years, he has regaled us with thrilling tales of plotting (and foiling) high-profile assassinations, unearthing Nazi war criminals, organising coups in Africa, kidnapping sons of US presidents, spy agencies' clandestine duels and their struggles against crime and terror. But Frederick Forsyth now tells his most magnificent tale - of his own life, during which he, among other foibles, nearly launched World War III.

Apart from this feat which he nearly accomplished while a correspondent in East Berlin and till today maintains “was not entirely my fault,” he reveals having “barely escaped the wrath of an arms dealer in Hamburg, been strafed by a MiG during the Nigerian Civil War, and landed during a bloody coup in Guinea-Bissau. The Stasi arrested me, the Israelis regaled me, the IRA prompted a quick move from Ireland to England, and a certain attractive Czech secret police agent - well...”

Apart from this feat which he nearly accomplished while a correspondent in East Berlin and till today maintains “was not entirely my fault,” he reveals having “barely escaped the wrath of an arms dealer in Hamburg, been strafed by a MiG during the Nigerian Civil War, and landed during a bloody coup in Guinea-Bissau. The Stasi arrested me, the Israelis regaled me, the IRA prompted a quick move from Ireland to England, and a certain attractive Czech secret police agent - well...”

There is much more in the extraordinary life of the author, of a chain of best-selling thrillers from “The Day of the Jackal” (1971) to “The Kill List” (2013). Forsyth here begins with a tale, that seems right out of W Somerset Maugham and Graham Greene, how his very existence itself may have hinged on the kindness of his father towards an employee in a rubber estate in Malaya in the mid-1930s.

We also learn how he mastered four foreign languages before growing out of teens, and became the youngest fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force - which he managed to join underage. Then came a eventful journalistic career, including in Charles De Gaulle's Paris (where the seeds of “The Day of the Jackal” were laid), and divided Berlin at the height of the Cold War, where there were frequent mind-games with the feared East German secret service, occasional espionage and the challenge of depleting the agency's burgeoning account of the externally-worthless local currency!

What, however makes the book stand out is Forsyth's account of Africa, and his experiences of the toll that imperialist mindsets continued to wreak on hapless Africans as some pointed recollections of the independence of media - or lack thereof!

A BBC correspondent then, he was sent to report on the Nigerian Civil War which broke out in 1967 after a coup and the secession of the eastern province of Biafra. Forsyth, who believed in making an assessment based on the ground situation, found out the British government was being misled by a biased envoy, and almost all media were following the government line without question. Even when proof to the contrary emerged, the government decided to follow its course rather than admit to having made a mistake - a precedent enough for what happened in Iraq three decades hence!

But as far as Africa is concerned, Forsyth's colourful but poignant account is a damning indictment of the lethal fault lines of colonialism left in a number of countries they created, with the potential for much havoc - and plentiful suffering - once their heavy hand was withdrawn. Nigeria was the first example, but the world never took heed - and stage was set for the tragedies of Rwanda and Darfur.

Also reason enough to pick up this book, which is not a structured autobiography as much as a collection of anecdotes told with wit and candour and thus more convivial, include how he ended up writing in some of his best known books, of encounters with nature and its fury and some invaluable tips on journalism and writing novels - which he tells us ranks well below robbing a bank as to a way to make quick money.

And why “Outsider”? Because “in a world that increasingly obsesses over the gods of money, power and fame, a journalist and a writer must remain detached, like a bird on a rail, watching, noting, probing, commenting but never joining. In short, he must be an outsider.”And as this book shows, he lived his creed.

By Vikas Datta

© 2025 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com