Bourdain's death reveals hope from depression

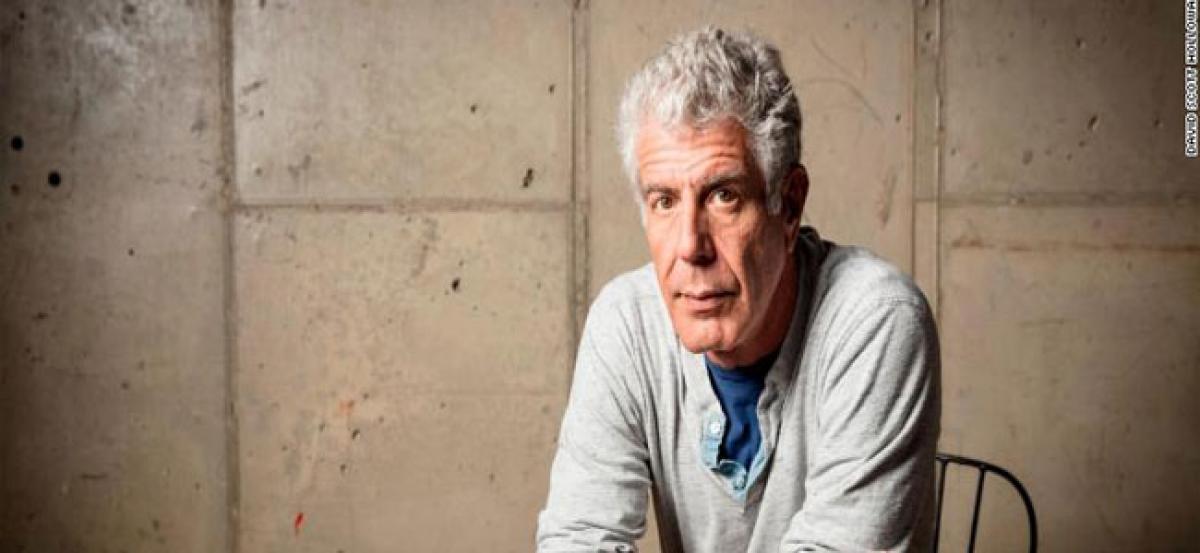

It’s been three weeks since the death of Anthony Bourdain, there has been gushing platitudes and an outpouring of sorrow from across the globe. The chef who exchanged his blade for a pen, and then for a charmingly attractive presence before the camera, Bourdain became in a way the rockstar of his ilk — a community of devious, murky, unpredictable and often criminal enterprise.

It’s been three weeks since the death of Anthony Bourdain, there has been gushing platitudes and an outpouring of sorrow from across the globe. The chef who exchanged his blade for a pen, and then for a charmingly attractive presence before the camera, Bourdain became in a way the rockstar of his ilk — a community of devious, murky, unpredictable and often criminal enterprise.

Bourdain’s several shows, through which he is credited, variously, as having brought local flavours of foreign cultures to the American world, having taught Americans not to automatically distrust the “other”, or even each other, and having brought about a new way of enjoying the most visceral of pleasures: “Your body is not a temple, it's an amusement park; enjoy the ride.” All of this is true.

It helped that he had an unabashedly soft corner for the underdog, a sneering contempt for power, pelf and privilege, and did not shy away from expressing quirky and often politically problematic views. To understand that, one has to go beyond the TV persona of the cook and delve into the books that he wrote, particularly two of his sort-of biographies, Kitchen Confidential and Medium Raw.

The first, coming out in 2000, is a tell-all about the unsavoury underbelly of the world of cuisine, the book that propelled its hitherto penniless and pretty unsuccessful author to fame. The second was published a decade later, the work of a more mature man who had tasted success and had been humbled by all that he did not know. In which he denounces Kitchen Confidential as a load of tripe, one that he is embarrassed to own given the cockiness and hubris that it exudes.

On the more palatable side, he once said, “I understand there’s a guy inside me who wants to lay in bed, smoke weed all day, and watch cartoons and old movies. My whole life is a series of stratagems to avoid, and outwit, that guy.” On the far side is an account Bourdain details in Medium Raw, of a period in his life when he would regularly take a late-night drive along a road at the top of a cliff, a road that involved a sharp, dangerous and deadly hairpin turn.

To many, such behaviours would appear deranged, the product of a starved mind that had probably been raised in a ghetto by parents who smoked crack. In fact, Bourdain’s was a happy, stable, middle-class childhood — the point being that the darkness — depression — can strike anywhere, at any time, any person, regardless of one’s background or life experience. Bourdain fought that darkness by flooding his world with light: of the cameras, of his travels, of his very genuine affection for the people that he met and the food he was privileged enough to be offered, be it as humble as a Jamaican pulled-pork sandwich. But the gathering dark got him in the end.